Factors affecting the levels and pathways of atmospheric brominated flame retardant uptake by humans in different weather conditions

Abstract

The health risks posed by atmospheric brominated flame retardants (BFRs) have been widely studied, but there remains a lack of clarity about exposure differences between clear days and haze days. We sampled the total suspended particle (TSP) and gaseous BFRs on clear days in summer, clear days in winter, and haze days in winter in Harbin, China, to investigate the variations in the concentrations and intakes (dermal and inhalation) in the different weather conditions. The concentrations of atmospheric BFRs were highest on haze days in winter

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Brominated flame retardants (BFRs) are widely used as additives for a wide range of products, including textiles, electronics, furniture, appliances, and interior decoration materials, to reduce their flammability[1,2]. BFRs include polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), of which several compounds, including penta-bromodiphenyl ether (penta-BDE), octa-bromodiphenyl ether (octa-BDE), and decabromodiphenyl ether (deca-BDE), are specifically listed in the Stockholm Convention and have been banned, because of their high persistence, bioaccumulation ability, and long-range transport potential[3]. As PBDEs have been phased out, novel brominated flame retardants (NBFRs)[2,4], such as decabromodiphenyl ethane (DBDPE), bis

Air pollution has emerged as a serious environmental issue in recent decades[7,8], and is the cause of much concern for both scientists and the general public[9-11], because of the risks to human health from exposure to large discharges of particulate matter (containing heavy metals and polyaromatic hydrocarbons), SO2 and NOx. Publics have recognised that abundant airborne particles during heavy haze days increased the risks of inhalation exposure. However, recent studies have reported that the risks to health from several semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs) were greater during light haze days than during heavy haze days, because of dermal intake[12-14], and we believe that this new finding deserves further research.

Atmospheric BFRs, such as BDE-209, can exist in the gas phase and particle phase at the same time, and the gas/particle partitioning varies with the temperature and the concentration of total suspended matter (TSP). Harner and Bidleman (1998) reported that the distribution of SVOCs in the gas phase and particle phase was determined by a temperature-dependent parameter (octanol-air partition coefficients, KOA), where the compounds with low KOA (with high temperature) trended to the gas phase and compounds with high KOA (with low temperature) trended to the particle phase[15]. However, TSP, as the main control on gas/particle partition, provides adsorption (defined by the specific surface area) or absorbing media (dominated by organic matters) for gaseous SVOCs, such that SVOCs may show a tendency to distribute on the particle phase during haze explosions[16]. These ongoing variations in SVOCs between the gas phase and particle phase[17] present a challenge for defining and understanding how health risks posed by atmospheric SVOCs vary with the weather and air quality.

Inhalation has long been recognized as the main exposure pathway for atmospheric BFRs and other SVOCs[18-22]. In recent years, in-depth studies of dermal exposure to BFRs have shown that a considerable proportion of the total atmospheric BFRs taken up by humans could permeate into the human body via dermal exposure[23-26]. It was recognized that BFRs in the particle and gas phases could enter the human body in different proportions, and that the amounts would vary by chemical, particularly for dermal absorption/permeation[27,28]. Therefore, in the light of these recent findings, it would be useful to determine how human exposure to, and the inhalation and dermal intakes of, atmospheric BFRs are affected by the weather and air quality.

In recent years, Harbin, a megacity in Northeast China, has experienced severe and continuous haze conditions in winter, which has had serious impacts on the social economy, ecological environment, and human health[29,30]. The temperature in Harbin can range from below -30 °C in winter to > 35 °C in summer, so Harbin provides an ideal research area to study how the weather and air quality influence human exposure to atmospheric BFRs. We collected gaseous and particle samples in August 2017, December 2017, and from December 2017 to January 2018 in different weather conditions, namely clear days in summer, clear days in winter, and haze days in winter, and analyzed them for 8 PBDEs and 8 NBFRs. We then

Materials And Methods

Sampling information

The sampling site was at an elevation of 15 m above the ground, on the roof of the School of Environment at the Second Campus of Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, Heilongjiang Province, China. During the sampling period, the temperatures ranged from -24 to 30 °C. The sampling period was divided into three weather conditions, defined as clear days in summer (August 2017), clear days in winter (December 2017), and haze days in winter (from December 2017 to January 2018). Detailed information about each sample is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Each sample was collected over a 24 h period using a medium-volume atmosphere sampler (Tisch-1000, Tisch Environmental, Inc. USA) with a flow rate 240 L min-1. The TSP samples were collected using glass fiber filters (GFF, ϕ110 mm) and gaseous samples were collected using polyurethane foam (PUF). Before the samples were collected, all the GFFs were baked in a muffle furnace at 400 °C for 8 h and cooled to room temperature in desiccators. The PUFs were extracted with acetone and n-hexane for 24 h, respectively, and then dried in a vacuum drying oven at 80 °C for 2 h and stored in sealed aluminum boxes. After sampling, the TSP samples were stored in a standard filter box that was packed with aluminum foil and then placed in a Ziploc bag. The PUF samples were sealed and kept at -28 °C until analyzed.

Experiments and detection levels

The TSP and PUF samples were prepared for analysis in line with the SVOCs standard pretreatment process of the International Joint Research Center for Persistent Toxic Pollutants (IJRC-PTS). The process involves Soxhlet extraction, concentration, purification, and concentration to 0.1 mL, and is described in detail in a previous study[31]. In total, the samples were analyzed for 16 BFRs, 8 PBDEs (BDE-17, BDE-28, BDE-47, BDE-66, BDE-99, BDE-138, BDE-183 and BDE-209), and 8 NBFRs [pentabromotoluene (PBT), pentabromoethylbenzene (PBEB), hexabromobenzene (HBBZ), 2,3-dibromopropyl 2,4,6-tribromophenyl ether (DPTE), 2-ethylhexyl-2,3,4,5-tetrabromobenzoate (EHTBB), BTBPE, bis BEHTBP and decabromodiphenylethane (DBDPE)]. The BFRs were determined qualitatively and quantitatively using an Agilent 7890B gas chromatograph coupled with a 5977A mass spectrometer in negative chemical ionization mode. The GC-MS had a DB-5MS (15 m × 0.25 mm × 0.1 μm, Company of J&W Scientific) chromatographic column. The GC was injected with a constant flow of helium (1.7 mL min-1) in splitless mode, with a single injection volume of 2 μL and an injection port temperature of 260 °C. The oven temperature was first maintained at 110 °C for 0.5 min, increased to 220 °C at a rate of 4.5 °C/min, increased to 280 °C at a rate of 15 °C/min, increased to 310 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min, and then held for 3 min. The temperature of the auxiliary thermal controllers between the GC and MS was 270 °C.

Quality assurance and quality control

The instrument detection limits (IDLs) were calculated using a three-times signal-to-noise ratio. Of the eight PBDEs, the IDL was highest for BDE-209 (0.15 ng/mL), and the IDLs of the other seven PBDEs ranged from 0.01 to 0.03 ng/mL. The IDL of DBDPE was 0.07 ng/mL, and the IDLs of the other seven NBFRs were lower than 0.01 ng/mL. C13BDE-209, BDE-71 and OCN were spiked into each sample as surrogate standards before extraction. Two pairs of field blanks (1 GFF + 1 PUF) and two pairs of experimental blanks were set for each weather type, where no individuals exceeded their corresponding IDL in any of the blanks. The eight PBDE individuals and eight NBFR individuals were all detected in the GFFs samples. In the PUF samples, BDE-138, BEHTBP, and DBDPE were detected at rates of 93%, 87%, and 87%, respectively, and the other BFR individuals had detection rates of 100%.

Gas/particle partitioning

The G/P partitioning quotient (KP) of SVOCs was defined as[16]:

where CP and Cg (both in pg/m3 of air) were the concentrations of the BFRs in the particle phase and gas phase, respectively, and TSP was the concentration of the total suspended particles (μg m-3 air) in air.

The Harner-Bidleman model (KPE) is frequently used to predict the G/P partitioning quotients of SVOCs in a state of equilibrium, and is calculated as[15]:

where fOM is the fraction of organic matter and TSP was assumed as 0.1. KOA was the octanol-air partitioning coefficient, which was a function of the ambient temperature (T, unit K):

where A and B were the Clausius-Clapeyron coefficients and the detailed values of A and B for eight PBDE and eight NBFR individuals are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

The Li-Ma-Yang steady-state model[32], established by Li et al., considers dry and wet deposition of SVOCs:

where the equilibrium term, log KPE, is given by Equation 2, and the non-equilibrium term, log α, is:

where C was 5 for urban sites.

Calculation of human intakes

Inhalation intake

The daily inhalation intake of gaseous BFRs [DIg, pg/(kg·day)] in the atmosphere was calculated

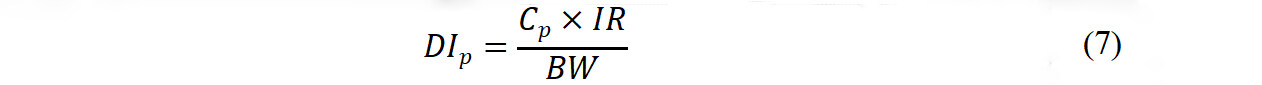

The daily inhalation intake of particulate BFRs (DIP) was calculated as[34]:

where IR was the human inhalation rate (16 m3/day), BW was the body weight (65 kg), and fA was the gas alveolar exchange rate (75%).

Dermal exposure intake

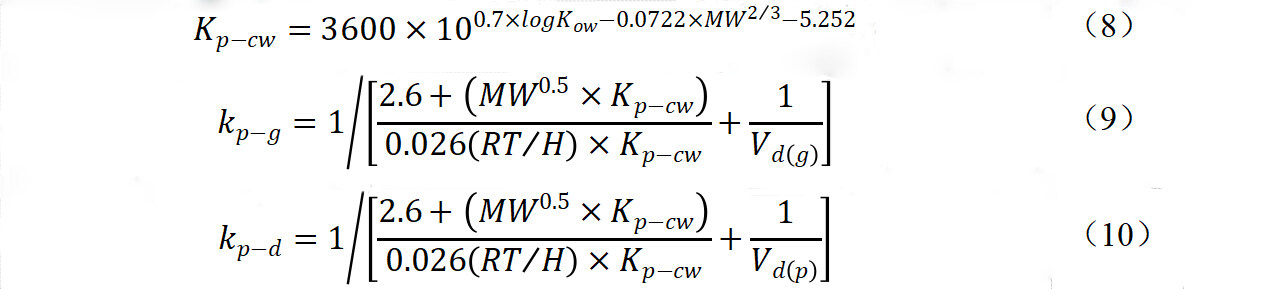

The dermal intake of gaseous and particle BFRs were estimated from the transdermal permeability coefficients kp-g and kp-d, respectively, using the equations derived from the model described by Weschler and Nazaroff[35], as follows:

Here, Kp-cw (cm/h) was the permeability coefficient that describes the transfer of the BFR compound through the stratum corneum with water as the medium that comes into contact with the skin, KOW (unitless) was the octanol-water partition coefficient of the BFR compound, and MW (g/mol) was the molecular weight of the corresponding compound. R (8.314 Pa m3/K/mol) was the ideal gas constant, T (305 K) was the skin temperature, and H [mol/(Pa m3)] was the Henry’s law constant. Vd(g) and Vd(p) (m/h) were the mass-transfer coefficients that describe the BFR compound from the gas and particle phases through the boundary layer adjacent to the skin, and were 6 and 1 m/h, respectively. The detailed parameters for each chemical are shown in Supplementary Table 2.

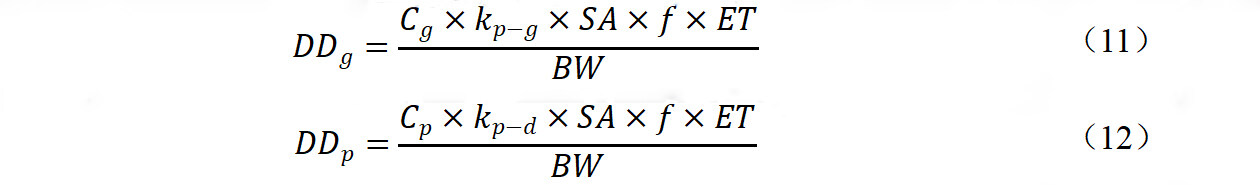

The daily dermal intake of gaseous [DDg, pg/(kg·day)] and particulate [DDP, pg/(kg·day)] BFRs were calculated using Equations 11 and 12.

where SA (m2) is the surface area of human skin, and f is the proportion of human skin exposed to air (only considering the head and hands, SA × f = 0.2 m2)[36]. ET is the daily exposure time (assumed to be 8 h/day in the outdoor environment). kp-g and kp-d (m/h) are the permeability coefficients of gaseous BFRs and particle BFRs, respectively, and are calculated with Equations 9 and 10. Data related to the human body were obtained from other studies[33].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Variations in the residual levels of atmospheric BFRs in different weather conditions

We investigated the concentrations of 16 BFRs, including 8 PBDEs and 8 NBFRs, in the atmosphere over Harbin during clear days in summer, clear days in winter, and haze days in winter. The weather and atmospheric conditions varied considerably in the three sampling periods. On clear days in summer, the temperature ranged from 15 to 30 °C and the AQI ranged from 46 to 61. On clear days in winter, the temperature ranged from -24 to -11 °C and the AQI ranged from 48 to 89. In the haze days in winter, the temperature ranged from -24 to -10 °C and the AQI ranged from 70 to 312 (for the detailed concentrations see Supplementary Table 3). The concentrations of the Σ16BFRs also varied between the different sampling periods and were lowest on clear days in winter and highest on haze days in winter. In addition, the concentrations varied between the particle phase and the gas phase for the different sampling periods, but without an obvious pattern. On clear days in winter, the geomeans (GM) (ranges) of the particle phase and the gas phase were 56.6 pg/m3 (43.5-73.9 pg/m3) and 21.7 pg/m3 (16.8-26.5 pg/m3), respectively. On clear days in summer, the GM (ranges) of the particle phase and the gas phase were 58.3 pg/m3 (41.3 to

The levels of Σ16BFRs (gas phase + particle phase) were higher on clear days in summer than on clear days in winter, which may indicate volatile BFRs sourced from their added substances (see Figure 1). Furthermore, the high levels of BFRs in the atmosphere during haze days reflect the higher amounts of airborne particles.

The GM concentrations and ranges of the Σ8PBDEs in the atmosphere in Harbin for the three weather types followed the same pattern as those of the Σ16BFRs, and were 32.5 pg/m3 (14.3-49.1 pg/m3) on clear days in winter, 47.9 pg/m3 (34.7-101 pg/m3) on clear days in summer, and 138.2 pg/m3 (77.3-182 pg/m3) on haze days in winter. For the three weather types, BDE-209 was the dominant congener and accounted for 86%, 83%, and 93% of the Σ8PBDEs, respectively. The percentage of BDE-209 was lower on clear days in summer than on clear days in winter, and may reflect the relative abundance of highly volatile individuals (such as BDE-17 and BDE-47) in summer. The Σ8NBFR distribution differed from the Σ16BFR and Σ8PBDE distributions, and the Σ8NBFR means (ranges) were highest on clear days in summer

Variations in BFRs with TSP in the different weather conditions

The GM concentrations of TSP in Harbin were 68.8 μg/m3 (61.9-80.4 μg/m3) on clear days in summer,

The relationships between the concentrations of BFRs and the concentrations of TSP were determined using Spearman correlation analysis. As shown in Supplementary Table 4 , the concentrations of Σ16BFRs (gas phase + particle phase) in the atmosphere were positively correlated with the concentrations of TSP

Gas/particle partitioning of BFRs in the three weather conditions

The distributions of the 16 BFRs between the particle phase and the gas phase in the three weather types are plotted in Figure 2. The PBDE and NBFR individuals were mostly dominated by the particle phase in all the weather types, with the exception of NBFRs on clear days in summer. The particle phase was highest on haze days in winter (PBDEs = 97.8%, NBFRs = 58.5%), followed by clear days in winter (PBDEs = 92.8%, NBFRs = 56.2%), and was lowest for clear days in summer (PBDEs = 86.7%, NBFRs = 15.9%). On the haze days in winter, the particulates accounted for more than 50% of all the PBDE and NBFR individuals. All the high molecular weight individuals (BDE-209, DBDPE, BBDE-183 and BEHTBP) were dominated by particulates for the three weather types. The low molecular weight individuals, such as PBT, PBEB, HBBZ, BDE-17, and BDE-28, were dominated by gas on clear days in summer and winter, especially PBT on clear days in summer, when 99.4% of the total PBT concentration was gaseous.

Figure 2. The distribution of the (A) 8 polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and (B) 8 novel brominated flame retardants (NBFRs) between the particle phase and the gas phase.

We investigated the gas/particle partitioning of BFRs in the three weather types, and compared them with the predictions of the equilibrium state model (Harner-Bidleman model) and the steady state model

On clear days in summer, the Harner-Bidleman model and the Li-Ma-Yang model predicted 66.2% and 76.6% of the monitoring data, respectively, and the gas/particle partitioning was mostly in the equilibrium domain (see Figure 3). On clear days and haze days in winter, the gas/particle partitioning of BFRs was similar, and was mostly in the maximum domain and remained at around -1.53. On these days, the Harner-Bidleman model predicted 25.0% and 35.4% of monitoring data, underestimated the non-monitoring data, and overestimated 75% and 64.6% of the monitoring data for clear and haze days, respectively. In contrast, the Li-Ma-Yang model agreed well with the monitoring data on clear (96.3%) and haze days (92.4%) in winter. It should be noted that the similar gas/particle partitioning patterns on clear and haze days in winter do not indicate similar gas and particle phase distributions. The high TSP concentrations on haze days provided abundant ab/adsorptive materials for BFRs, but did not change the ab/adsorptive abilities of TSP.

Variation in the human intake of BFRs in different weather conditions

We evaluated the human intake of atmospheric BFRs in the different weather conditions from the dermal intakes (DD) and the inhalation intakes (DI) of BFRs on clear days in summer, clear days in winter, and haze days in winter. The human intakes (DD + DI) were highest on haze days in winter [49.6 pg/(day·kg)], followed by clear days in summer [32.8 pg/(day·kg)], and clear days in winter [21.2 pg/(day·kg)]

Figure 4. The human intakes of atmospheric brominated flame retardants (BFRs) in the three weather types.

To gain insights into how the different weather types influenced the human intakes of BFRs, we analyzed the contributions of gaseous and particulate BFRs to both the dermal intakes and inhalation intakes of the 16 BFRs (see Figure 5). Gaseous BFRs accounted for most of the dermal intake on clear days in winter (69.5%), followed by clear days in summer (52.0%), and haze days in winter (38.8%). Further, the contributions of gaseous and particulate BFRs to the inhalation intake were consistent with their phase distribution among the three weather types, and gaseous BFRs were highest on clear days in summer and lowest on haze days in winter, while particulate BFRs were lowest on clear days in summer and highest on haze days in winter.

Discussion

The differences in the human intakes of atmospheric BFRs in the three weather conditions may be attributed to, among other factors, the different intake pathways (dermal and inhalation) and the degree of exposure. The dermal intake and inhalation intake of atmospheric BFRs result from different exposure mechanisms. BFRs taken in by inhalation may enter the human respiratory system directly when an individual breathes, such that the intake doses of both gaseous and particulate BFRs vary with their atmospheric concentrations. Dermal exposure involves two main processes, where (1) particulate and gaseous chemicals are ad/absorbed by surface skin; and (2) BFRs on the surface skin permeate into the human body through the dermal. The ad/absorption fluxes of particulate and gaseous BFRs were different, and the fluxes for gaseous BFRs were much greater than the fluxes of particulate BFRs, depending on the particle size. However, the permeation process varied by chemical, and tended to increase with the molecular weight. These differences between dermal exposure and inhalation exposure meant that individual BFRs with high molecular weights, especially gaseous individuals, entered the human body more easily than those with low molecular weights. As such, the high residual levels of PBT experienced on clear days in summer would only contribute noticeably to the inhalation intake but not the dermal intake.

Behavior habits also affect human exposure to atmospheric BFRs. The inhalation intake of atmospheric BFRs was noticeably higher than the dermal intake in the three weather conditions; thus, residents who wear face masks effectively reduce the exposure risk to atmospheric BFRs via inhalation. The dermal intakes of BFRs were calculated from the dermal areas of the hand and head only. However, people might expose their arms and legs to the air in summer, thereby increasing the exposure area, or wear hats, gloves, and masks in winter, which decreases the exposure area, meaning that people with different habits will have different BFR intakes.

CONCLUSIONS

The differences in the residual levels and human intakes of atmospheric BFRs in clear days in summer, clear days in winter, and haze days in winter were investigated in this study. When the concentrations of TSP are high, e.g., on haze days, there is the potential for high ad/adsorption of gaseous BFRs that may escape from indoor environments. The levels of PBT will be high on clear days in summer when there is an obvious local source of PBT, meaning that the BFR concentrations could be higher on clear days in summer than on clear days in winter. The human intake of BFRs tended to follow the same pattern as their atmospheric concentrations, and was mostly dominated by the inhalation exposure pathway. The dermal intake was not, but the inhalation intake was, affected by the concentrations of low-molecular weight gaseous BFRs.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributionsWriting - original draft, writing - review & editing, data curation, visualization, supervision: Hu R

Writing - original draft, writing - review & editing, data curation, visualization: Zhong S

Writing - review & editing: Liu D

Data curation: Wang L

Methodology: Yu H

Conceptualization, project administration: Cao Z

Project administration, writing - review & editing: Li Y

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materialsThe authors do not have permission to share data.

Financial support and sponsorshipThis work was supported by the State Key Laboratory of Urban Water Resource and Environment (Harbin Institute of Technology) (No. 2019DX04), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42077341), the Postdoctoral Research Foundation of Henan Normal University (5101219470246), the Scientific Research Starting Foundation of Henan Normal University (5101219170829), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42122057, 41977308) and the University Science and Technology Innovation Talent Support Program of Henan Province (20HASTIT011).

Conflicts of interestAll authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participateNot applicable.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

Copyright© The Author(s) 2023.

Supplementary MaterialsREFERENCES

1. Birnbaum LS, Staskal DF. Brominated flame retardants: cause for concern? Environ Health Perspect 2004;112:9-17.

2. Covaci A, Harrad S, Abdallah MA, et al. Novel brominated flame retardants: a review of their analysis, environmental fate and behaviour. Environ Int 2011;37:532-56.

3. Convention S. All POPs listed in the Stockholm Convention. Available from: http://chm.pops.int/TheConvention/ThePOPs/AllPOPs/tabid/2509/Default.aspx [Last accessed on 8 Dec 2022].

4. Papachlimitzou A, Barber JL, Losada S, Bersuder P, Law RJ. A review of the analysis of novel brominated flame retardants. J Chromatogr A 2012;1219:15-28.

5. Xiong P, Yan X, Zhu Q, et al. A review of environmental occurrence, fate, and toxicity of novel brominated flame retardants. Environ Sci Technol 2019;53:13551-69.

6. Kuramochi H, Takigami H, Scheringer M, Sakai S. Estimation of physicochemical properties of 52 non-PBDE brominated flame retardants and evaluation of their overall persistence and long-range transport potential. Sci Total Environ 2014;491-492:108-17.

7. Wang Y, Zhang Y, Tan F, et al. Characteristics of halogenated flame retardants in the atmosphere of Dalian, China. Atmospheric Environ 2020;223:117219.

8. Wang L, Deng J, Yang L, Yu T, Yao Y, Xu D. Dynamic analysis of particulate pollution in haze in Harbin city, Northeast China. Open Geosciences 2021;13:1656-67.

9. Rajagopalan S, Al-Kindi SG, Brook RD. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:2054-70.

10. Gautam D, B. Bolia N. Air pollution: impact and interventions. Air Qual Atmos Health 2020;13:209-23.

11. Jerrett M. Air pollution as a risk for death from infectious respiratory disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022;205:1374-5.

12. Lao JY, Xie SY, Wu CC, Bao LJ, Tao S, Zeng EY. Importance of dermal absorption of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons derived from barbecue fumes. Environ Sci Technol 2018;52:8330-8.

13. Cao Z, Chen Q, Ren M, et al. Higher health risk resulted from dermal exposure to PCBs than HFRs and the influence of haze. Sci Total Environ 2019;689:223-31.

14. Fan Y, Chen Q, Wang Z, et al. Identifying dermal exposure as the dominant pathway of children’s exposure to flame retardants in kindergartens. Sci Total Environ 2022;808:152004.

15. Harner T, Bidleman TF. Octanol-air partition coefficient for describing particle/gas partitioning of aromatic compounds in urban air. Environ Sci Technol 1998;32:1494-502.

16. Yamasaki H, Kuwata K, Miyamoto H. Effects of ambient temperature on aspects of airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Environ Sci Technol 1982;16:189-94.

17. Meng Y, Zhang H, Qiu Y, et al. Seasonal distribution, gas-particle partitioning and inhalation exposure of brominated flame retardants (BFRs) in gas and particle phases. Environ Sci Eur 2019:31.

18. Wang D, Wang P, Zhu Y, et al. Seasonal variation and human exposure assessment of legacy and novel brominated flame retardants in PM2.5 in different microenvironments in Beijing, China. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2019;173:526-34.

19. Pal VK, Khwaja HA. Personal exposure and inhaled dose estimation of air pollutants during travel between Albany, NY and Boston, MA. Atmosphere 2022;13:445.

20. Li Y, Chen L, Ngoc DM, et al. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in PM2.5, PM10, TSP and gas phase in office environment in Shanghai, China: occurrence and human exposure. PLoS One 2015;10:e0119144.

21. Jin R, Liu G, Jiang X, et al. Profiles, sources and potential exposures of parent, chlorinated and brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in haze associated atmosphere. Sci Total Environ 2017;593-594:390-8.

22. Li L, Arnot JA, Wania F. How are humans exposed to organic chemicals released to indoor air? Environ Sci Technol 2019;53:11276-84.

23. Cao Z, Zhao L, Zhang Y, et al. Influence of air pollution on inhalation and dermal exposure of human to organophosphate flame retardants: a case study during a prolonged haze episode. Environ Sci Technol 2019;53:3880-7.

24. Goede H, Christopher-de Vries Y, Kuijpers E, Fransman W. A review of workplace risk management measures for nanomaterials to mitigate inhalation and dermal exposure. Ann Work Expo Health 2018;62:907-22.

25. Andersen C, Krais AM, Eriksson AC, et al. Inhalation and dermal uptake of particle and gas-phase phthalates-a human exposure study. Environ Sci Technol 2018;52:12792-800.

26. Silva EZM, Dorta DJ, de Oliveira DP, Leme DM. A review of the success and challenges in characterizing human dermal exposure to flame retardants. Arch Toxicol 2021;95:3459-73.

27. Weschler CJ, Nazaroff WW. Dermal uptake of organic vapors commonly found in indoor air. Environ Sci Technol 2014;48:1230-7.

28. Weschler CJ, Bekö G, Koch HM, et al. Transdermal uptake of diethyl phthalate and Di(n-butyl) phthalate directly from air: experimental verification(. EHP ;123:928-34.

29. Zhu G, Wang Q, Tang Q, Gu R, Yuan C, Huang Y. Efficient and scalable functional dependency discovery on distributed data-parallel platforms. IEEE Trans Parallel Distrib Syst 2019;30:2663-76.

30. Luo Y, Liu S, Che L, Yu Y. Analysis of temporal spatial distribution characteristics of PM(2.5) pollution and the influential meteorological factors using Big Data in Harbin, China. J Air Waste Manag Assoc 2021;71:964-73.

31. Hu PT, Ma WL, Zhang ZF, et al. Approach to predicting the size-dependent inhalation intake of particulate novel brominated flame retardants. Environ Sci Technol 2021;55:15236-45.

32. Li YF, Qiao LN, Ren NQ, Sverko E, Mackay D, Macdonald RW. Decabrominated diphenyl ethers (BDE-209) in Chinese and global air: levels, gas/particle partitioning, and long-range transport: is long-range transport of BDE-209 really governed by the movement of particles? Environ Sci Technol 2017;51:1035-42.

33. Xu H, Du S, Cui Z, Zhang H, Fan G, Yin Y. Size distribution and seasonal variations of particle-associated organochlorine pesticides in Jinan, China. J Environ Monit 2011;13:2605-11.

34. Yadav IC, Devi NL, Zhong G, Li J, Zhang G, Covaci A. Occurrence and fate of organophosphate ester flame retardants and plasticizers in indoor air and dust of Nepal: implication for human exposure. Environ Pollut 2017;229:668-78.

35. Weschler CJ, Nazaroff WW. SVOC exposure indoors: fresh look at dermal pathways. Indoor Air 2012;22:356-77.

36. China Environment Publishing Group. Ministry of Ecology and Environment. Exposure factors handbook of chinese population, 2013. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/294646021_zhongguorenqunbaolucanshushouce_Exposure_Factors_Handbook_of_Chinese_Population [Last accessed on 8 Dec 2022].

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].