Recent advances in wearable fiber-shaped supercapacitors: materials, design, and applications

Abstract

The rapid development of wearable electronic products necessitates flexible and efficient energy storage solutions. Fiber-shaped supercapacitors (FSSCs) have gained significant attention as promising substitutes owing to their flexibility, low weight, and ability to integrate seamlessly into textile and wearable applications. This review offers an in-depth examination of the latest developments in FSSCs, distinguishing itself by not only summarizing diverse electrode materials such as carbon-based, polymer-based, and novel MXenes but also exploring their unique properties and applications in depth. We critically examine various fabrication techniques that enable the customization of fiber structures, including wet-spinning, electrostatic spinning, melt spinning, co-spinning, and advanced three-dimensional (3D) printing methods. Furthermore, we investigate innovative design strategies aimed at enhancing performance, such as film/sheet twisting for increased surface area and multilayer integrated designs. By discussing the integration of FSSCs into applications such as energy storage devices and sensors, we shed light on their potential to revolutionize the field. The review wraps up by identifying future challenges and directions, underlining the critical need for advancements in material synthesis, device design, and integration strategies. These advancements are crucial for the widespread adoption of FSSCs in flexible and wearable electronics. Continued research holds the potential to deliver next-generation energy storage solutions tailored to the growing demands of the wearable technology industry.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The relentless march of wearable devices is transforming how we interact with our environment, perform tasks, and conduct our daily activities. From fitness trackers to smartwatches, wearable devices increasingly demand compact, flexible, and efficient power sources to sustain their functionality[1,2]. Traditional power sources often fall short in meeting the unique requirements of wearable devices because of their bulky size, limited adaptability, and slow charging times. Competing technologies, such as lithium-ion (Li+) batteries and traditional capacitors, while effective in various applications, do not offer the same degree of flexibility and lightweight integration essential for wearable devices. In this context, fiber-shaped supercapacitors (FSSCs), on the other hand, emerge as a promising alternative, offering high flexibility, lightweight nature, and seamless integration into textiles and wearable devices[3]. Their ability to store energy quickly and efficiently, combined with their adaptability to various forms and shapes, positions them as ideal solutions for powering the future of wearable technologies.

The incorporation of FSSCs into wearable electronics introduces unique challenges that go beyond traditional energy storage requirements. One major challenge is ensuring mechanical durability under continuous stress, such as flexing, elongating, and twisting, which are common in wearable applications. FSSCs must maintain high energy density and stable capacitance even under these stresses, which demands advanced materials and innovative structural designs. Additionally, achieving seamless integration with textile-based substrates requires flexible, lightweight, and breathable designs that do not compromise user comfort. Another significant challenge lies in the miniaturization and scalability of FSSCs, as wearable devices often demand compact power sources without sacrificing performance. To address these challenges, recent trends in FSSC development have focused on multifunctional materials that combine energy storage with additional functionalities, such as self-healing, biocompatibility, or sensing capabilities. Moreover, there is growing interest in developing eco-friendly and sustainable FSSC materials to align with the environmental priorities of the wearable electronics industry. These emerging trends underscore the critical need for continued innovation in FSSC design and fabrication to fulfill the rigorous requirements of wearable devices. Therefore, addressing these interconnected challenges related to material selection, fabrication, and integration is important for unlocking the full capabilities of FSSCs in wearable technology[4-7].

This review offers an in-depth examination of the latest developments in FSSCs, focusing on the materials, design strategies, and diverse applications driving this burgeoning field. We begin by highlighting the diverse array of electrode materials employed in FSSCs, ranging from carbon nanotubes (CNTs)[8-13], graphene[14-18], carbon fibers, and activated carbon fibers (ACFs)[19-22] [Figure 1]. This exploration delves into their unique advantages and challenges, and the fabrication techniques used to create fibers with tailored structures. The ongoing search for novel materials with even higher conductivity and surface area is a particularly exciting area of research, promising significant improvements in energy density and power output. Next, we delve into the innovative design strategies employed to optimize FSSC performance. This includes a detailed examination of specific spinning techniques such as wet-spinning and electrospinning, alongside the emerging potential of 3D-printing approaches. The capability to accurately manipulate fiber structure and design through these techniques is essential for optimizing ion transport and electrochemical performance. Moreover, exploring novel architectures, such as core-shell or hierarchical structures, holds immense promise for further enhancing FSSC performance. Finally, we summarize the potential applications of FSSCs, spanning energy storage, power supply, and even sensor applications. This is perhaps the most compelling aspect of FSSCs, as their unique form factor and flexibility open doors to seamless integration into textiles, wearable electronics, and even implantable medical devices. The ability to power these devices with energy storage woven directly into the fabric itself represents a paradigm shift in wearable technology.

Figure 1. Key components driving the development of fiber-shaped supercapacitors (FSSC), categorized into four focus areas: Mechanisms (EDLC, pseudo-capacitance, hybrid systems), Materials (carbon-based, polymer-based, others), Technologies (spinning, 3D printing, twisting), and Applications (energy storage, power supply, sensing). This framework highlights the critical design considerations advancing FSSCs for wearable electronics. Schematic FSSC image: Reproduced with permission[23]. EDLC: Electrochemical double-layer capacitance.

MECHANISMS ANALYSIS

FSSCs function according to the energy storage principles of supercapacitors[24] [Figure 2], including (1) Electrochemical double-layer capacitance (EDLC), where ions from the electrolyte gather at the interface between the electrode material and the electrolyte[25]; (2) Pseudo-capacitance (PC), which involves very fast, reversible Faradaic redox reactions, electrosorption, or intercalation processes occurring at the surface of suitable electrodes[26,27]; and (3) Hybrid supercapacitors (HSC), which take advantage of both mechanisms[28].

Figure 2. Illustrative schematics of (A) EDLC, (B) PC, (C) HSC. Reproduced with permission[24]. EDLC: Electrochemical double-layer capacitance; PC: pseudo-capacitance; HSC: hybrid supercapacitor.

Electrochemical double-layer capacitance

The primary mechanism of most FSSCs is the electrical EDLC, which depends on the establishment of an electrical double layer at the interface between the electrode material and the electrolyte. This double layer comprises two oppositely charged regions: The Stern Layer: Located directly at the electrode surface, this layer is composed of electrolyte ions that bind to the electrode through electrostatic forces. The Diffuse Layer: Situated next to the Stern layer, this region contains ions that are weakly bound to the electrode surface.

Upon the application of an electric potential, ions from the electrolyte move toward and accumulate at the electrode surface, establishing a charge-separated double-layer structure. This configuration is facilitated by the large surface area of high-porosity materials such as activated carbon (AC) or metal oxides, enabling the supercapacitor to store substantial charge through physical adsorption, without involving faradaic (redox) reactions.

The EDLC energy storage process involves two primary phases: adsorption and desorption. In the adsorption phase, ions are adsorbed into the pores of the electrode because of the material's high porosity, creating an effective charge separation. During desorption, reversing the potential prompts these ions to migrate back into the electrolyte, releasing stored energy. The capacitance of an EDLC is primarily dependent on the active area of the electrode material. However, at very high active surface areas, the capacitance tends to saturate, as factors such as pore structure and electrolyte accessibility impose physical limits on charge storage[29-31] [Figure 3].

Figure 3. Models that illustrate the electrical double layer formed at a positively charged surface: (A) the Helmholtz model; (B) the Gouy-Chapman model; and (C) the Stern model, each illustrating different approaches to the distribution of charge and potential across the interface. Reproduced with permission[32].

Pseudo-capacitance

PC plays a crucial role in enhancing the performance of FSSCs. Unlike traditional electrochemical EDLCs, which rely solely on electrostatic interactions for charge storage, pseudocapacitors introduce reversible redox reactions, electrosorption, and intercalation between the electrode/electrolyte interface[33]. As illustrated in Figure 4, these processes facilitate direct charge transfer between the electrode material and the electrolyte. This key distinction enables pseudocapacitors to achieve significantly higher capacitance and energy density compared to EDLCs. Typically, pseudocapacitor electrodes comprise electroactive transition metal oxides (TMOs) or hydroxides that facilitate redox reactions during charging and discharging, allowing these materials to store charge directly through faradaic processes.

Figure 4. Schematics of charge-storage mechanisms of different types of pseudocapacitive electrodes. Reproduced with permission[33].

In essence, while EDLCs rely on electrostatic charge separation, pseudocapacitors involve highly reversible redox reactions or chemical adsorption-desorption within the electrode’s surface or within quasi-two-dimensional spaces of active material layers. During the charging process, ions from the electrolyte diffuse to the electrode’s surface and undergo redox reactions, penetrating the electrode’s active oxide phase. The large specific surface area of oxide enables a significant number of these reactions, resulting in considerable charge storage. During discharge, ions move back to the electrolyte, allowing the stored charge to flow through the external circuit, exemplifying the faradaic charge and discharge mechanism[34,35].

Pseudocapacitors can deliver specific capacitance values ten to 100 times greater than EDLCs when using electrodes of equivalent surface area, enabling them to be highly advantageous for applications requiring enhanced energy storage capability. In FSSCs, PC provides several critical electrochemical benefits, including improved energy density, rapid charge/discharge rates for fast energy delivery and increased cycling stability for long-term performance. These advantages make FSSCs with pseudocapacitive properties well-suited for applications across wearable devices, electric vehicles, and even grid-scale energy storage systems[36].

Hybrid supercapacitor

Hybrid capacitors consist of one electrode based on a double-layer capacitor and another resembling a battery electrode. The double-layer capacitor electrode enables fast charge response, increasing the rate, while the battery-type electrode uses redox or ion embedding reaction to boost capacity, as seen in

Furthermore, the HSC mechanism allows for a wider operational voltage window compared to symmetric FSSCs. This is accomplished by carefully pairing positive and negative electrodes with distinct electrochemical potentials in an asymmetric configuration. The resulting increase in voltage directly contributes to a higher energy density, since energy is directly related to the square of the voltage[39,40]. In essence, the HSC mechanism successfully mitigates the inherent energy density limitations of conventional FSSCs.

Role of the electrolyte

The electrolyte is essential to the functioning of FSSCs, as it enables ion movement between the electrodes and supports charge balance throughout the cycling process. The choice of electrolyte is crucial for optimizing the performance of FSSCs. Gel electrolytes are particularly favored for FSSCs owing to their distinct blend of ionic conductivity and structural strength. Their semi-solid nature provides structural integrity, preventing leakage and ensuring reliable operation under mechanical operation, all essential for wearable applications. The most common gel electrolytes for FSSCs are based on various functional polymers [including polyvinyl alcohol[41], poly (ethylene glycol)[42], polyvinylidene fluoride

The categories of gel electrolytes are classified based on their composition as follows: (I) aqueous gel polymer electrolytes, in which the organic polymer structure is readily dissolvable in water; (II)

Research efforts are increasingly focused on developing advanced gel electrolytes with higher ionic conductivity, wider operational temperature ranges, improved safety, and enhanced mechanical properties. These innovations are essential to overcoming current limitations and enhancing the performance and practicality of FSSCs for diverse wearable applications.

FIBER ELECTRODE MATERIALS, DESIGN, AND APPLICATIONS OF FSSCS

Fiber electrode materials are the heart of FSSCs, dictating their performance, flexibility, and integration into wearable electronics. Careful design and fabrication of these electrodes are critical to achieving high power density, energy density, and high cycle durability, all while maintaining the mechanical robustness required for bending, twisting, and stretching. Table 1 outlines the main materials, types, and key properties of fiber supercapacitors. The discussion covers the strengths and limitations of various functional materials, such as traditional carbon-based fibers, emerging oxides, and polymers. It will also explore the relationship between material selection, electrode contraction, and the performance of FSSCs in powering future wearable technologies.

Structure design and performance of the FSSCs

| Electrode materials | Configurations | Specific capacitance | Power density | Energy density | Stability |

| PANI-TPU fiber[49] | Two-ply | 45.12 F cm-3 at | 65.1% after 3,500 cycles | ||

| Ti3C2Tx quantum dots fiber[50] | Parallel | 413 F cm-3 at 0.5 A cm-3 | 97% after 10,000 cycles | ||

| NaV3O8/RGO //Ti3C2Tx fiber[51] | Two-ply | 76 F cm-3 at 0.1 A cm-3 | 75 % after 2,000 cycles. | ||

| (Fe2O3-x@RGO) core-sheath fiber[52] | Parallel | 525.2 F cm-3 at 5 mV s-1 | 97.1% after 5,000 cycles | ||

| 3D-direct-ink-writing fiber[53] | Sandwich-type | 1.062 F cm-2 | 92% after 25,000 cycles | ||

| High-entropy doped metal oxide@graphene fiber[54] | Parallel | 1,446.78 mF cm-2 at | 81.05% after 10,000 cycles | ||

| CuS|P-CuGF fiber[55] | Coaxial | 1,460.9 mF cm-2 at | 94.3% after 500 cycles | ||

| NiFe2O4@ slit modified hollow carbon fiber[56] | Coaxial hollow | 225.4 F g-1 at 1 A g-1 | 100% after 5,000 cycles | ||

| Core-shell NiCoMoS-Ti3C2Tx fiber[57] | Parallel | 2,472.3 F cm-3 at | 85.2% after 2,000 bending cycles at 60° | ||

| PPy/GCHF core-sheath fiber[58] | Coaxial | 791.9 mF cm-1 at | 88.7 % from 120° bending after 5,000 cycles | ||

| Co3O4@c-fPI@CF//c-fPI@CF[59] | Parallel | 56 F cm-3 at 0.5 A cm-3 | 92% after 8,000 cycles | ||

| Ti3C2Tx/TPU/PPy fiber[60] | Parallel | 41.2 F-1 (5 mV s-1) | 83 % after 10,000 cycles | ||

| Ni(OH)2@A-ZnCoNi-LDH[61] | Coaxial | 2,405 mF cm-2 at | 95% after 7,000 cycles | ||

| LC-spun CNTFs[13] | Parallel | 192.4 F cm-3 at 0.5 A g-1 | 100% after 10,000 cycles | ||

| MXene/MoO3-x fibers[62] | Parallel | 869.1 F cm-3 at | 86.4% after 5,000 cycles |

Materials and structure of FSSCs

Carbon-based fiber materials and structure

Carbon-based materials offer significant advantages for fiber electrodes due to their accessibility, versatility, ease of functionalization, and ability to achieve large specific surface areas along with mechanical flexibility[63-65]. For FSSCs, achieving superior performance requires the fiber electrodes themselves to possess large specific surface areas. Additionally, the electrodes must facilitate rapid ion channels between them while ensuring fast axial and radial electron transport. Therefore, the choice and design of materials and structures are crucial. Improving the functionality of FSSCs involves refining the morphology and architecture of the carbon-based materials to maximize their electrochemical properties[66,67]. This includes designing hierarchical porous structures that not only enhance the active area but also furnish efficient pathways for ion diffusion and electron conduction[68,69]. Integrating conductive polymers or metal oxides with carbon-based fibers can further improve conductivity and capacitance, leading to enhanced energy storage capabilities[70]. Moreover, scalable and sustainable fabrication methods are essential to produce

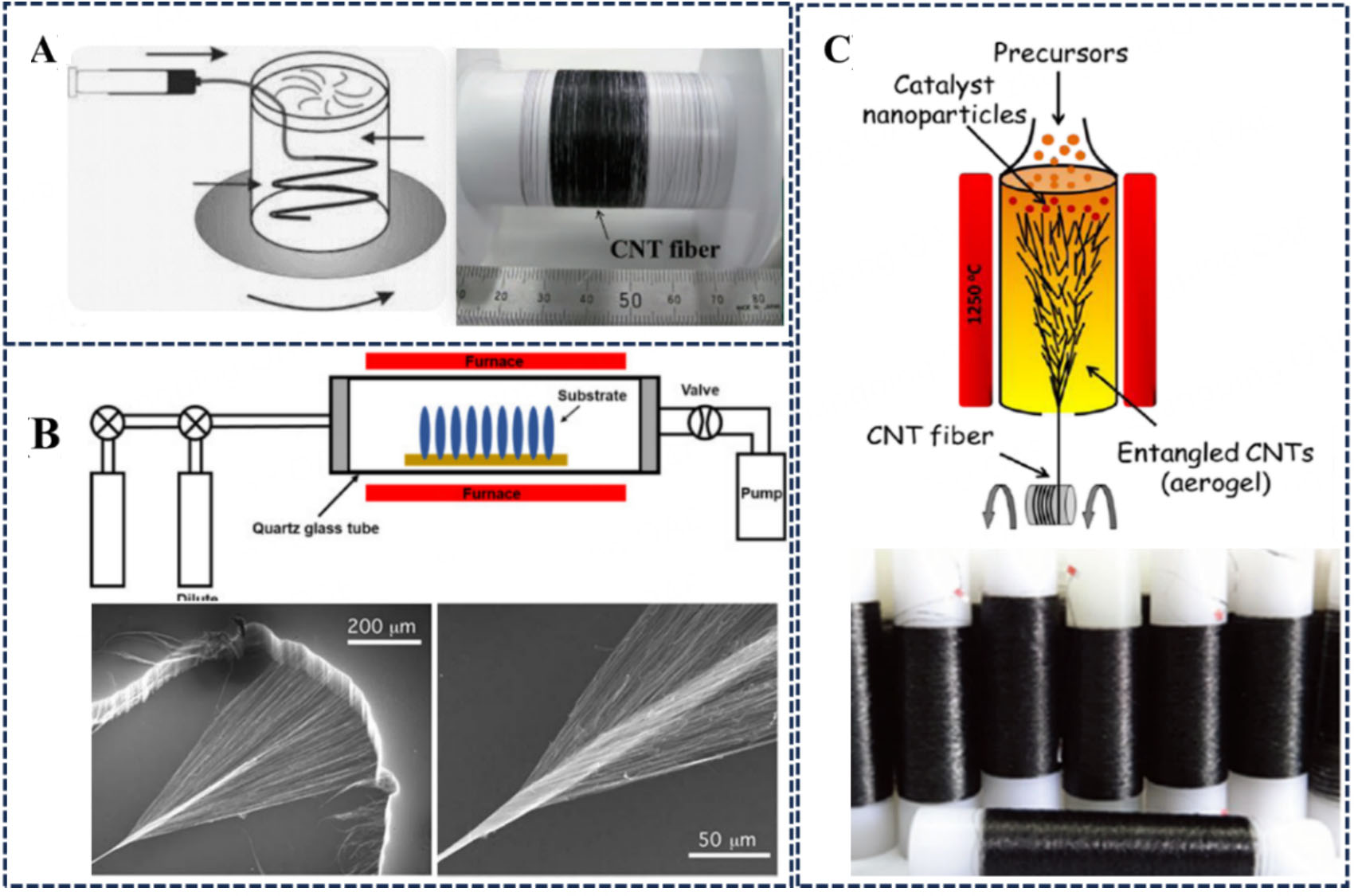

Due to their exceptional physical and chemical properties, CNTs have become promising candidates for electrode materials. Assembling CNTs into fiber structures provides a viable platform to extend these nanoscale advantages to the macroscale. These methods include wet spinning based on the coagulation process[71-75], fiber spinning from vertically aligned CNT arrays[76-79], and direct spinning from pre-formed CNT gels during the growth process[80-83]. The role of CNT-based materials in fiber supercapacitors is significant given their unique structural features and functional attributes. CNT fibers offer a large surface area, superior conductivity, and strong mechanical properties, rendering them ideal for flexible and wearable devices[84,85]. Combining CNT fibers with pseudocapacitive materials, such as conducting polymers (CPs) or metal oxides, can further enhance their performances by providing additional redox-active sites. For example, Yang et al.[86] designed a CNT/graphene fiber supercapacitor through a wet-spinning process, utilizing a specially designed multi-channel spinneret. Consequently, the fiber supercapacitor exhibited a 187.6 mF cm-2 specific capacitance, excellent electrochemical stability (93% of preserved after 10,000 cycles), and remarkable flexibility, and successfully applied to textile. Zhang et al.[87] introduced an innovative sheath-core architecture for CNT yarn and a continuous spinning process for its fabrication, enabling the production of long linear supercapacitors. The yarn is directly spun from vertically aligned CNT arrays, with a thin CNT layer encapsulating a metal filament core. This architecture significantly enhances electrochemical performance and allows for scalable fabrication of supercapacitors with extended lengths. The resulting flexible threadlike supercapacitor is well-suited for integration into large-area fabrics, opening exciting possibilities for wearable electronic applications. Senokos et al.[83] report the fabrication of flexible supercapacitors (FSCs) through direct spinning of a CNT network from pre-formed CNT gels during

In addition, the typical structure of these fiber supercapacitors often involves the arrangement of electrodes and electrolytes in various configurations to optimize their performance and flexibility. These structures can be classified into parallel, two-ply, and coaxial designs [Figure 6][89]. The parallel configuration features two fibers, each containing a positive and negative CNT electrode, aligned side by side with a gel electrolyte in between. The twisted design interweaves the CNT electrodes and gel electrolytes into a helical structure, which enhances mechanical stability and flexibility. Lastly, the coaxial configuration arranges the CNT electrodes and gel electrolytes concentrically, offering improved uniformity and energy density. These configurations demonstrate the versatility of fiber supercapacitors, each providing unique benefits for different applications. For example, our group synthesized Au-decorated CNT sheets, incorporating polyaniline (PANI) to enhance radial ion diffusion coupled with axial electron conduction [Figure 7A][90]. The resulting wire-shaped supercapacitor, fabricated by twisting two PANI@Au@CNT yarns, achieved a high capacitance of 6 F cm-3 at 10 V s-1, with consistent performance across different electrode diameters due to its high conductivity. Furthermore, we fabricated stretchable supercapacitors using buckled linear electrodes, which kept a stable performance of ~0.2 F cm-3 under 400% strain and exhibited 95% capacitance retention over 1,000 cycles. Additionally, we designed a stretchable FSSC by wrapping CNT/MnO2 nanosheets on spandex yarn. The resulting FSSCs exhibit a high stretchability of up to 80%, with ultrahigh electrochemical performance. These FSSCs also demonstrate excellent mechanical flexibility and ultralong cycle life [Figure 7B][91].

Figure 6. Schematic illustrating the classification of flexible solid-state fiber supercapacitor device. Reproduced with permission[89].

While CNT-based fibers have demonstrated significant potential for supercapacitor applications,

Chemical modifications and composites with other materials are commonly employed strategies. For instance, reduced graphene oxide (RGO) exhibits larger surface area and improved conductivity, leading to enhanced capacitance and power density in supercapacitors[94,95], and catering to the demand for flexible electronics[96,97] [Figure 8]. Li et al.[52] introduced a simple hydrogen reduction strategy to synthesize

Figure 8. Schematic showing graphene-based or composite fibers supercapacitors. (A) Morphology and application of coaxial polyelectrolyte-wrapped graphene/CNT core-sheath fibers. Reproduced with permission[96]; (B) The fabrication of Fe2O3-x@RGO asymmetric fiber electrodes and supercapacitors. Reproduced with permission[52]; (C) Diagram of the fabrication process of

Despite its remarkable properties, graphene has notable limitations. Firstly, its production processes, particularly high-quality methods such as chemical vapor deposition (CVD), are costly and often lack scalability, which restricts its commercial feasibility. Secondly, the hydrophobic nature of graphene can hinder its dispersibility in solvents, making it challenging to integrate into composites uniformly. Thirdly, the biocompatibility and environmental impact of graphene are still under investigation, with concerns over potential toxicity, particularly if inhaled as nanoparticles. Lastly, graphene’s electrical and mechanical properties are sensitive to defects and layer stacking, which can complicate performance consistency in large-scale applications.

Common fabrication methods for graphene-based fiber supercapacitors include electrospinning[100], CVD[101], and template methods[102]. Electrospinning is a highly adaptable technique enabling the production of high-surface-area, 3D network structures of graphene fibers. However, it often requires high voltage and complex fabrication processes. CVD can produce high-quality graphene films but requires specific reaction conditions and equipment. Template methods enable the fabrication of graphene structures with specific shapes and sizes, but the process is more complex and expensive due to the need for templates.

Carbon fibers, one-dimensional materials comprising long, thin filaments of carbon possess remarkable mechanical strength, high tensile modulus, and good electrical conductivity. Unlike CNTs, which are hollow cylindrical structures, and graphene, carbon fibers are solid and exhibit a higher aspect ratio. This unique structure enables efficient ion transport and enhanced mechanical strength, rendering them ideal for high-performance energy storage applications.

Carbon FSSCs have emerged as promising candidates for energy storage because of their inherent advantages, such as high strength, excellent electrical conductivity, and high aspect ratio. The unique

Various approaches have been utilized to improve the electrochemical performance of carbon fiber-based FSSCs. One common approach involves surface modification of carbon fibers by introducing functional groups, such as oxygen-containing groups, which can increase the surface area and improve wettability, thereby boosting capacitance[103,104]. Furthermore, incorporating conductive polymers or metal oxides onto carbon fibers can enhance their conductivity and create composite structures with improved electrochemical properties [Figure 9][105]. For example, Chiu et al.[106] report the successful achievement of a roughened surface, and the production of graphene quantum dots and functional groups through acid treatment of carbon fiber, particularly with acid mixtures. The optimized carbon fiber electrode, treated with an HNO3 to H2SO4 ratio of 1 to 3, exhibited a significantly enhanced specific capacitance and energy density. Another strategy is to design hierarchical structures with controlled porosity to facilitate ion diffusion and improve the rate capability of FSSCs. Hierarchical porous carbon fiber (HPCF) was prepared through phase-separable wet-spinning of polyacrylonitrile (PAN), followed by pre-oxidation and carbonization under tension. The applied tension during pre-oxidation and carbonization, along with elevated carbonization temperatures, improved the carbon structure’s order and graphitization degree, resulting in HPCF with high strength (326.95 MPa)[107].

While carbon fiber offers excellent strength-to-weight ratio and stiffness, it has several limitations. Firstly, the production process is costly and energy-intensive, particularly for high-strength grades, which limits its accessibility for cost-sensitive applications. Secondly, carbon fiber has low impact resistance and can be brittle, making it prone to sudden fractures under heavy impact, unlike materials with higher ductility. Thirdly, recycling carbon fiber is complex, as it does not melt and is challenging to reshape, which raises sustainability concerns. Finally, its electrical conductivity can be a disadvantage in applications where insulation is required, potentially leading to unintentional interference in electronic systems.

Beyond CNTs, graphene, and carbon fibers, other carbon-based fiber materials have shown promise in fiber supercapacitor applications. For example, ACFs exhibit excellent electrochemical performance due to their high active area, rich pore structure, and good electrical conductivity. Studies have demonstrated that ACFs can be further modified through chemical activation, template methods, and other techniques, resulting in superior capacitance and stability in fiber supercapacitors[108-111]. For example, Li et al.[112] reported a composite of manganese dioxide and ACFs, featuring high MnO2 mass loading and a microporous structure, utilized as a fiber electrode for FSCs.

Additionally, emerging carbon-based fiber materials such as carbon nanofiber bundles[113-115], hollow carbon fibers[116-118], and carbon aerogel fibers[83,119,120] are gaining attention in fiber supercapacitor research. These materials not only inherit the advantages of carbon-based materials but also exhibit unique structural characteristics, providing new pathways for the development of fiber supercapacitors. For example, carbon nanofiber bundles offer interconnected networks that provide rapid ion transport pathways, enhancing the power density of the supercapacitor. Hollow carbon fibers, with their open structures and increased surface area, can facilitate efficient ion diffusion and electrolyte penetration, leading to improved capacitance and rate performance[116,121]. Carbon aerogel fibers, with their 3D interconnected porous network, provide large active area, good conductivity, and excellent flexibility, making them attractive for high-performance fiber supercapacitors[122,123].

However, the fabrication of these novel carbon-based fiber materials is complex and costly, hindering their large-scale applications. Future research needs to focus on exploring cost-effective fabrication methods for these materials, optimizing their structure and performance, to facilitate their practical application in fiber supercapacitors.

Polymer-based fiber materials and structure for FSSCs

Polymer-based materials play a crucial role in the construction of fiber supercapacitors, acting as the structural backbone and providing the necessary flexibility and processability. These materials offer a unique combination of properties, including tunable conductivity and easy fabrication, making them ideal for creating high-performance and adaptable energy storage devices.

In practical applications, polymer-based materials can serve as substrates for fiber supercapacitors, such as those designed and fabricated using various fabrics and yarns. Additionally, incorporating CPs with high PC can further enhance the performance. CPs such as poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT): poly(styrenesulfonate) polypyrrole (PPy) and PANI are widely used in the design and fabrication of fiber supercapacitors due to their unique electrochemical properties and adjustable structures[17,124]. These fiber supercapacitors based on CPs exhibit excellent electrochemical performance and outstanding mechanical properties, meeting the requirements of various practical applications. For example, Zhang et al.[125] proposed fiber supercapacitor devices using porous-hollow-conductive composite fibers (PHCFs) with a multilayer structure. The nanoporous PHCFs significantly enhanced surface area and pore volume, without affecting mechanical properties. This structure facilitated high mass loading and efficient utilization of PANI, resulting in fiber electrodes with excellent capacitance and exceptional cycle stability over thousands of cycles. Zheng et al.[91] designed a stretchable fiber supercapacitor by wrapping high-capacity CNT-MnO2 fibers around aramid elastic fibers using a synchronous winding method. This supercapacitor exhibited high stretchability (~80%) and ultrahigh capacitances of over 680 mF cm-2. Chen et al.[49] fabricated a thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) film using electrospinning and incorporated PANI via in situ polymerization. By twisting the PANI-TPU fiber film, they developed a fiber supercapacitor that remained stable under large tensile deformations. The PANI-TPU fiber exhibited excellent tensile strain tolerance, and the supercapacitor maintained stable, high capacitance even under significant strain. Hossain et al.[126] presented a multilayer device composed of cotton fibers, CNTs, and transition metal carbides/nitrides, fabricated using a dry spinning method, which significantly enhances both strain sensing and supercapacitor functionality. The design approach markedly influenced capacitance, correlating with the percentage of active material used. Through systematic optimization, the fiber device exhibited a capacitance 26-fold greater than that of a standard neat CNT fiber, emphasizing the crucial role of innovative design and high active material loading in improving device performance. Polymer-based materials used in FSSCs offer flexibility and lightweight characteristics, yet they have several drawbacks. Firstly, their relatively low electrical conductivity, even after doping or modification, limits their performance compared to carbon-based or metal oxide materials, affecting both energy and power densities. Secondly, polymer-based materials can have limited thermal and electrochemical stability, particularly under high-voltage operation or in harsh environments, which can affect their long-term durability and reliability in wearable applications. Thirdly, achieving consistent and scalable fabrication of polymer-based electrodes with high performance remains challenging, as they can suffer from processing issues such as poor adhesion and uneven coating. Finally, the environmental impact of synthetic polymers, including potential toxicity and recycling difficulties, is an ongoing concern, especially as FSSCs become more prevalent in sustainable and wearable electronics.

Other materials and structure for FSSCs

TMOs such as MnO2[127-129], RuO2[130-133], and NiO[134,135] have been widely studied for their use in FSSCs due to their ability to provide high capacitance through Faradaic reactions. These materials are often utilized as active electrode materials, nanostructured coatings, or within hybrid composites. Currently, TMOs are primarily combined with other fiber substrates to fabricate fiber supercapacitor electrodes, as synthesis methods such as solution-phase chemical precipitation and hydrothermal treatment are not well-suited for creating fiber morphologies. To address these challenges, wet spinning and electrospinning design strategies have been employed to create TMO fibers with nanostructures that offer large surface areas and superior electrochemical properties. Notably, high-energy-density FSSCs using TMO nanoribbon yarns have been developed, demonstrating impressive capacitance and energy storage capabilities. These nanoribbon yarns, with their distinctive structural features, also provide enhanced mechanical flexibility and durability, rendering them well-suited for wearable electronics[136-138]. Ahn et al.[136] proposed high-performance FSSCs based on TMO nanoribbon yarns and fabricated through delamination of nanopatterned TMO/metal/TMO trilayer arrays. The arrays were fabricated by depositing target materials onto a nanoline mold, followed by selective plasma etching to suspend the nanoribbons into twisted yarn structures. Direct formation of TMOs on Ni electrodes resulted in FSSC devices with excellent electrochemical performance and stability, particularly when using CoNixOy nanoribbon yarns and graphene fibers. Furthermore, the fiber supercapacitor was integrated with a pressure sensor, triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG), and flexible light-emitting diode (LED) for enhanced functionality. Xu et al.[139] developed CP/TMO hybrid fibers by directly injecting a solution into a capillary, creating PEDOT sulfonate/vanadium pentoxide fibers. These fibers demonstrated good electrochemical performance and cyclic stability, retaining ~94.0% capacity after 4,000 cycles. The energy density of the PEDOT/V2O5 fiber in gel electrolyte reached 1.37 μWh cm-2, significantly lower than the 21.46 μWh cm-2 achieved in organic electrolyte.

MXenes, a burgeoning class of two-dimensional transition metal carbonitrides[140,141], have been investigated for high-performance energy storage devices, including fiber supercapacitors[142-144]. Their unique combination of metallic conductivity, high active area, and hydrophilic nature makes them ideal candidates for enhancing the performance of fiber-based energy storage systems[57,145]. MXenes can be directly incorporated into fiber electrodes or combined with other materials to create composite structures with enhanced properties[146-152]. For example, Zhang et al.[149] developed a scalable wet-spinning method to create fibers using Ti3C2Tx nanosheets and PEDOT, achieving a record conductivity of 1,489 S cm-1 [Figure 10A]. Assembled into a free-standing supercapacitor, the device reached energy and power densities of

Figure 10. Schematic showing Mxene based or composite fibers supercapacitors. (A) Schematic illustration of MXene flakes and PEDOT: PSS chains. Reproduced with permission[149]; (B) Schematic of the production of Ti3C2Tx /carbon nanofibers via electrospinning. Reproduced with permission[150]; (C) Diagram of wet-spun gel MXene fiber and demonstration of supercapacitor application. Reproduced with permission[152]. PEDOT: Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene); PSS: poly(styrenesulfonate).

Design of FSSCs

From the choice of materials to the design of the structure we can find that various technologies have been developed to achieve high-performance and large-scale production of FSSCs. These technologies primarily focus on the realization of fiber electrodes, including a range of spinning techniques such as wet spinning, electrospinning, melt spinning, and co-spinning, as well as 3D printing, film/sheets winding and twisting into fibers, among others. Additionally, some emerging technologies are continually being introduced. These fabrication techniques not only enhance the energy storage performance of fiber supercapacitors but also significantly improve their mechanical properties and processability, thus offering great potential for large-scale applications.

Spinning technique design

Spinning techniques are essential for constructing FSSCs. These techniques determine the morphology, mechanical properties, and electrochemical performance of the fiber electrodes. The primary spinning techniques used in the production of fiber electrodes include wet spinning, electrospinning, melt spinning, and co-spinning [Figure 11]. Each of these techniques has unique advantages and challenges.

Wet spinning

Wet spinning [Figure 11A] involves extruding a solution containing polymers, natural polymers, inorganic materials, or composite materials through a spinneret into a coagulation bath, where the material solidifies into fibers[153,156-159]. This technique is particularly useful for producing fibers from materials that do not melt easily. It allows for the incorporation of various functional materials, such as nanoparticles, conductive materials, and metal oxides, resulting in fibers with specific properties and high performance[160-162]. Wet spinning enables precise control over fiber diameter and morphology, essential for optimizing the performance of supercapacitors, and results in electrodes with high conductivity and flexibility. For example, Yang et al.[163] utilized a three-channel wet-spinning spinneret to produce RGO@carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC)@RGO fibers by injecting graphene oxide (GO) and a reduction agent into separate channels, with CMC solution as an intermediate phase for structural formation. The resulting flexible

However, the wet-spinning method has several significant limitations. First, its complexity and cost arise from the need for specialized equipment and hazardous solvents, which elevate production expenses. Additionally, the post-treatment steps required to remove residual solvents further complicate the process and add to the cost, while also raising environmental concerns. The challenges associated with solvent recovery, recycling, and safe disposal contribute to potential environmental pollution and necessitate strict safety protocols. Another challenge is achieving consistent fiber properties on a large scale. Variations in fiber diameter, porosity, and surface morphology during wet spinning can lead to inconsistencies in electrochemical performance and mechanical properties, which can hinder the development of reliable and reproducible supercapacitor devices. Furthermore, wet-spun fibers often exhibit lower mechanical strength and flexibility compared to fibers produced by other methods. This limitation restricts their applicability in wearable electronics, where mechanical robustness and conformability are essential[73,74,164].

In conclusion, while wet spinning presents a promising approach for fabricating high-performance fibers for supercapacitors, its inherent complexities, environmental impact, and limitations in mechanical properties highlight the need for careful consideration and potential exploration of alternative fabrication techniques.

Electrospinning

Electrospinning uses an electric field to draw a polymer solution or melt into ultrafine fibers [Figure 11B]. This technique results in a high surface area-to-volume ratio, significantly enhancing the electrochemical performance of the fibers. The high surface area and porosity make electrospun fibers particularly suitable for creating high-capacitance electrodes in fiber supercapacitors. Moreover, the versatility of electrospinning allows for the use of a wide range of materials, including polymers, composites, and nanomaterials, enabling the customization of fiber properties for specific applications. Electrospinning offers precise control over fiber morphology, which is crucial for optimizing ion transport and electrolyte access in supercapacitor electrodes. This method also allows for the incorporation of various functional materials, such as conductive polymers, metal oxides, and carbon-based nanomaterials, to further enhance the electrochemical properties of the fibers. For example, Liu et al.[165] developed an all-fiber FSC using composite nanofiber electrodes made via electrospinning. By adding manganese acetylacetonate to PAN and treating it thermally, the supercapacitor's performance improved from 90 to 200 F g-1 and the electrospun separators outperformed commercial Celgard separators. Bai et al.[166] reported a one-step method to fabricate gel-electrolyte fiber-shaped aerogel electrodes via electrospinning. The process creates curly poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrenesulfonate) (PP)-poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) nanofiber aerogels coated on titanium wire. The unique curly morphology, resulting from the electrospinning conditions, enhances porosity and hydrophilicity, improving electrolyte absorption and reducing contact resistance.

While electrospinning has notable advantages for fabricating fiber supercapacitors, it faces several significant challenges. Scalability is a major issue, as electrospinning is primarily a laboratory-scale technique, and scaling it to industrial production involves considerable technical and economic challenges. The need for high-voltage equipment and strict environmental controls adds to the complexity of scaling up. Material compatibility is another limitation; not all polymers and composites are suitable for electrospinning. Some materials may not form continuous fibers, while others require complex solvent systems, raising safety and environmental concerns[167,168]. Finally, achieving consistent fiber morphology is crucial but challenging. Variations in fiber diameter and properties across large areas can significantly influence the electrochemical performance and mechanical integrity of the resulting electrodes. Ensuring uniformity and reproducibility remains an active area of research in electrospinning for supercapacitor applications.

Melt spinning

Melt spinning is a process where the precursor material is melted and extruded through a spinneret to form continuous fibers [Figure 11C], which solidify upon cooling. This technique is efficient and scalable, eliminating the need for solvents. In FSSCs, melt spinning is used to produce fibers with controlled properties. It allows for the creation of high-performance electrodes by integrating conductive materials into the fiber matrix. This method enables the production of binder-free electrodes with tailored characteristics, enhancing the efficiency and stability of the supercapacitors. Wang et al.[110]. fabricated ACFs with a controlled pore structure using melt spinning. Low-cost Kraft hardwood lignin served as the raw material, and nano-SiO₂ was used as a hard template. The resulting fibers exhibit optimal pore structure, mechanical strength, and hydrophilicity, making them suitable as binder-free electrodes for FSCs.

Melt spinning offers a scalable method for producing fiber-based supercapacitor electrodes but faces several challenges. Achieving high electrical conductivity requires precise optimization of conductive filler dispersion and surface modification. Controlling porosity for effective electrolyte access and ion transport can be difficult, often needing additional techniques such as stretching or template-assisted spinning. Aligning fibers to enhance conductivity is another challenge, necessitating improved alignment methods. Additionally, the cost of conductive fillers and specialized equipment poses challenges for large-scale production.

Co-spinning

Co-spinning is a technique involving the simultaneous extrusion of two or more precursor materials or components through a single spinneret, presenting a unique avenue for tailoring the properties of fibers for supercapacitor applications [Figure 11D]. By carefully selecting polymer blends, co-spinning allows for the creation of composite fibers with synergistic properties. For instance, significant improvement was achieved by coaxially co-spinning GO with a polyelectrolyte protective layer, followed by a twisting process of the two coaxial fibers to enhance structural integrity and electrochemical performance[96]. Sun et al.[169] introduced a wearable scaffold for yarn supercapacitors by co-spinning cotton fibers and urethane elastic fibers (UY) to create high-stretchability yarns. This innovative approach combined CNT dipping and PPy electrodeposition in a scalable two-step process, resulting in yarn supercapacitors with a high areal capacitance of 69 mF cm-2 and excellent performance even at 80% strain. The use of co-spun UY yarns eliminates the need for additional stretchable substrates or wavy structures, paving the way for large-size, high-performance stretchable supercapacitors in wearable electronics.

Co-spinning enables the fabrication of core-shell fibers, where a conductive core is encapsulated within a porous shell, optimizing both conductivity and electrolyte accessibility. This level of control over fiber composition and morphology opens exciting possibilities for designing high-performance supercapacitor electrodes with tailored electrochemical characteristics. However, challenges remain in achieving uniform co-extrusion, maintaining stable jetting, and controlling the interfacial interactions between the different polymers during the spinning process.

3D-printed technique design

The technique of 3D printing is emerging as a transformative technology for the fabrication of supercapacitor electrodes, particularly for fiber-based designs. It allows for the precise, layer-by-layer deposition of conductive inks or filaments, enabling the creation of intricate 3D architectures with tailored properties.

The ability to control fiber orientation, porosity, and surface area through 3D printing offers significant advantages. Interconnected fiber networks can be fabricated, maximizing the contact area of the

Figure 12. (A) 3D-direct-ink-writing printing of FSSCs, fabrication, structure, and device demonstrations. Reproduced with permission[53]; (B) Fabrication process and structural characterization of the fiber-shaped asymmetric supercapacitors. Reproduced with permission[170]; (C) Schematic of printing coaxial FASC device by DCMW technology, structure, morphology, demonstration. Reproduced with permission[171]. 3D: Three-dimensional; FSSCs: fiber-shaped supercapacitors; FASC: fiber-shaped asymmetric supercapacitors; DCMW: direct coherent multi-ink writing.

Three-dimensional printing offers significant potential for fabricating fiber-based supercapacitor electrodes but faces several challenges. High printing resolution is essential for creating precise fiber structures with the desired porosity and surface area, though current techniques may not match traditional methods in accuracy. Uniform ink deposition is critical; variations in viscosity, nozzle clogging, or droplet size can lead to inconsistencies in fiber diameter and porosity, affecting electrochemical performance. Additionally, scaling up 3D printing for mass production is challenging due to time and cost constraints. Addressing these issues through the development of high-throughput printing methods, optimizing ink formulations, and exploring new printing platforms will be crucial for making 3D-printed supercapacitors commercially viable and advancing fiber-based supercapacitor technology.

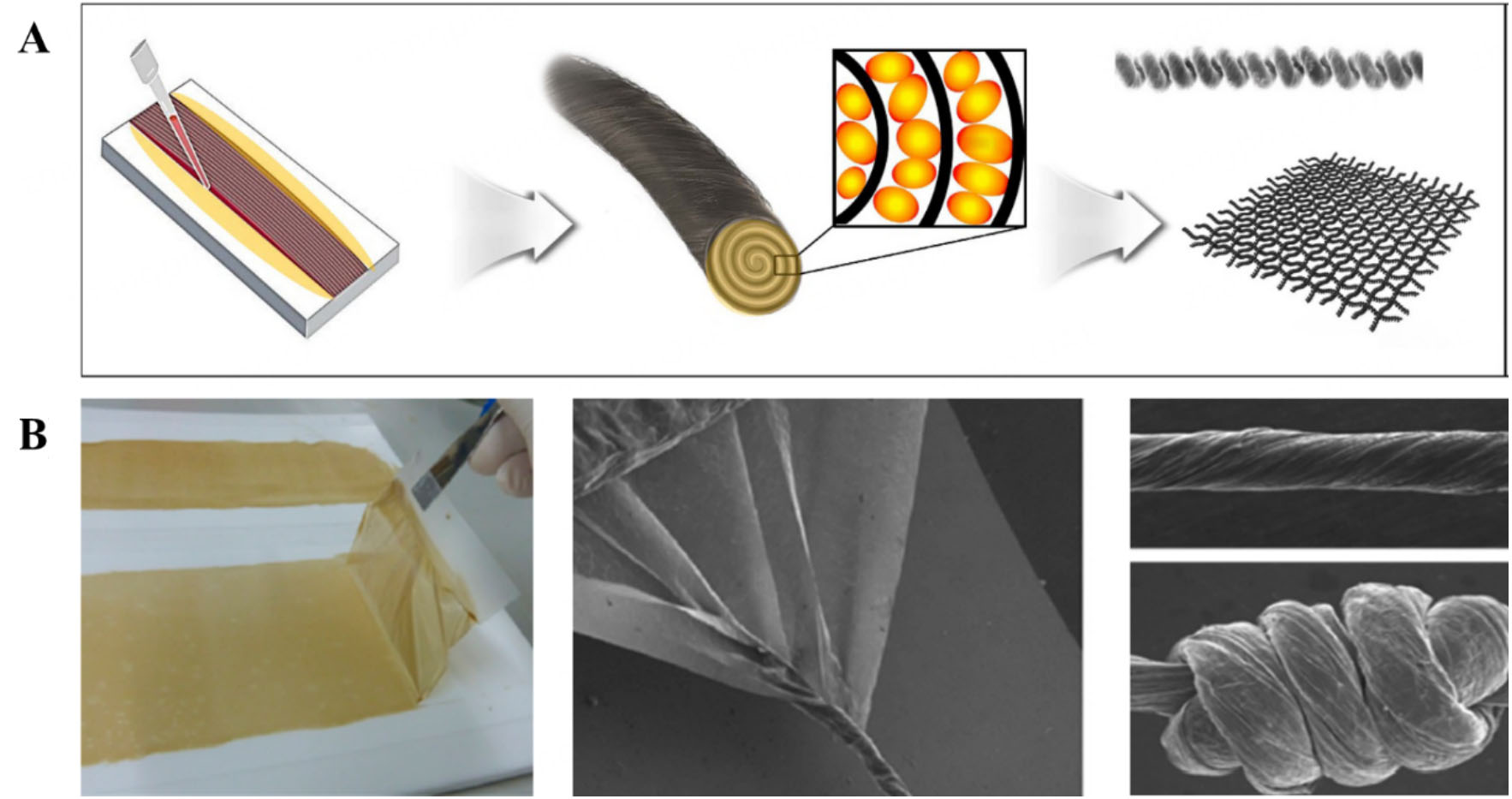

Film/sheets twist design

The film/sheet twist design represents an innovative approach for fabricating FSSCs. This technique involves twisting thin films or sheets of active materials into a fibrous form, combining the advantages of high surface area and flexibility. These films can be loaded with various active substances through physical or chemical deposition methods before or after being twisted into fibers. Additionally, the materials chosen are either inherently strong films or those whose strength is significantly enhanced when twisted into fibers. The film/sheet twist design is particularly beneficial for achieving high energy density and mechanical robustness in FSSCs.

For instance, in 2011, Lima et al. first proposed the concept of loading functional materials onto CNT sheets and fabricating them into fiber electrodes through twisting [Figure 13A]. This method enabled the development of devices such as FSSCs, battery electrode materials, and fuel cell electrodes[172]. In 2014,

However, the film/sheet twist design presents several challenges that must be resolved to fully unleash its potential. First, ensuring the uniformity of twists is critical, as non-uniform twists can lead to variations in electrochemical activity and mechanical stability, thereby affecting overall performance. Second, the materials used for the films or sheets must be compatible with the twisting process and subsequent integration steps; issues such as brittleness or poor adhesion can significantly hinder the performance of the supercapacitor. Finally, efficient integration of the electrolyte with the twisted structure is necessary to achieve optimal ionic conductivity and charge storage. This step can be particularly challenging due to the complex geometry of the twisted films.

Other technology design

In addition to spinning, 3D printing, and film/sheet twisting techniques, other innovative approaches have been developed to realize versatility of FSSCs. Two notable designs are the multilayer structure and integrated design. These approaches aim to maximize the electrochemical performance, mechanical flexibility, and scalability of supercapacitors.

The multilayer structure design involves stacking multiple layers of active materials to form a composite electrode, significantly enhancing the energy density and mechanical properties of the supercapacitor. This design can be achieved through various deposition techniques such as layer-by-layer assembly, vacuum filtration, or spray coating, enabling the sequential deposition of different materials to create a composite structure[175]. Each layer can be optimized for specific functions, such as providing high conductivity, large surface area, or mechanical support. Material selection is crucial in the multilayer structure design. Commonly used materials include conductive polymers (e.g., PANI and PEDOT), carbon materials (e.g., graphene and CNTs), and oxides (e.g., MnO2 and RuO2)[132,176,177]. The combination of these materials can result in a synergistic effect, enhancing overall performance. Proper engineering of the interfaces between layers is essential to ensure good adhesion and minimize resistance. Techniques such as surface functionalization or the use of intermediate binding layers can improve interlayer bonding and electrical connectivity.

The integrated design approach aims to combine multiple components of the supercapacitor into a single, cohesive structure, enhancing compactness, functionality, and ease of integration into various applications. Key elements of this approach include all-in-one structures, monolithic integration, functional integration, and design flexibility. All-in-one structures incorporate current collectors, active materials, and electrolytes into a single assembly, reducing complexity and enhancing mechanical stability. Techniques such as printing or co-deposition facilitate this integration[170,171,178]. Monolithic integration goes a step further by fabricating the entire supercapacitor as a single piece, eliminating the need for separate assembly steps. Advanced manufacturing methods such as 3D printing enable the creation of flexible and stretchable supercapacitors through monolithic integration. Functional integration adds further value by incorporating additional functionalities such as sensors, energy harvesting elements, or electronic circuits into the supercapacitor design[41,140,170]. This multifunctionality broadens the potential applications of FSSCs, particularly in smart textiles and wearable electronics. Moreover, integrated designs offer high flexibility in terms of shape and size, allowing for customization to fit specific applications, such as conforming to the contours of wearable devices or fitting into irregular spaces. This integrated approach not only enhances the performance and versatility of supercapacitors but also simplifies their deployment in innovative applications.

Wearable applications

FSSCs have significant potential in wearable applications due to their mechanical flexibility, lightweight nature, and high energy density. They can seamlessly integrate into wearable devices, providing reliable energy storage and power supply and functioning as sensor media.

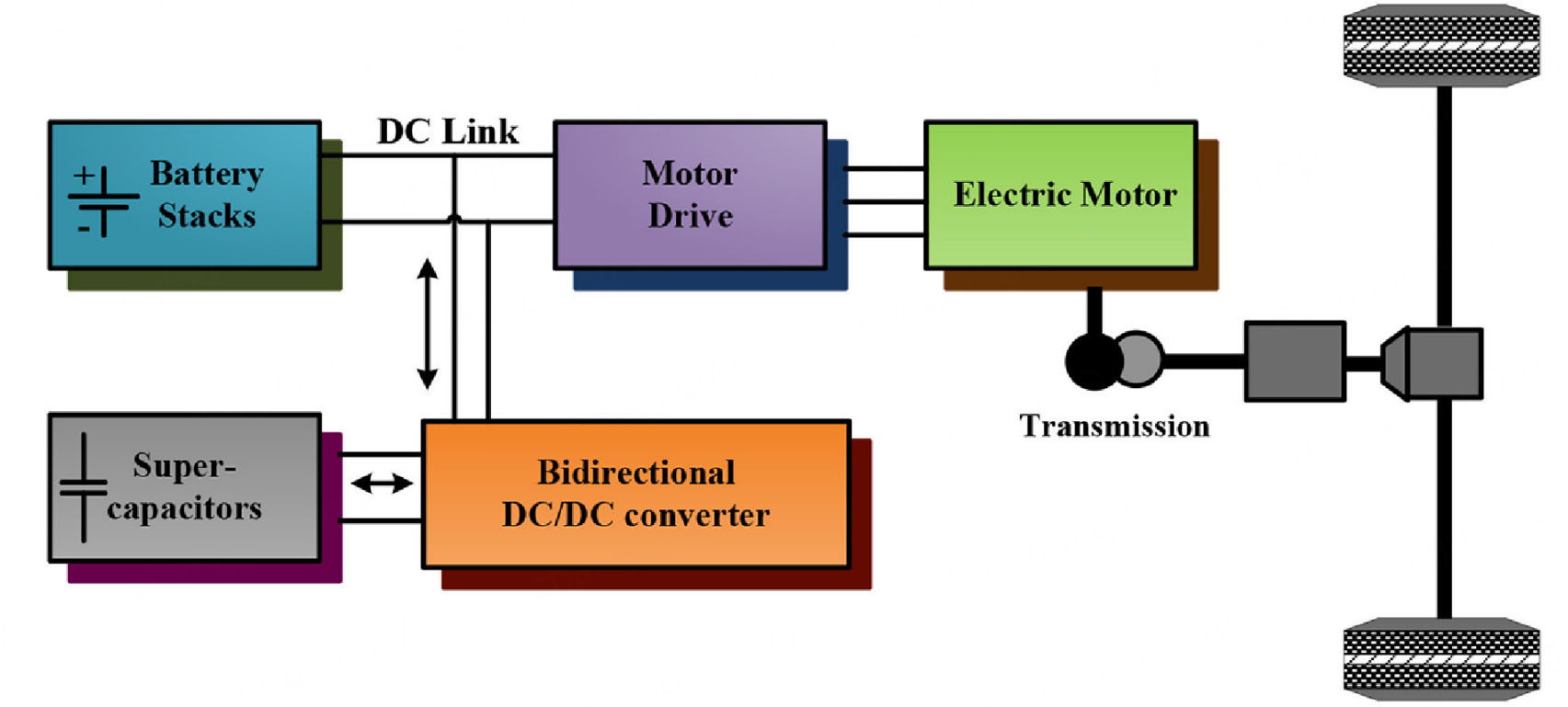

Energy storage (Assisted)

In wearable technology, energy storage is critical for ensuring the continuous operation of various devices, and supercapacitors can serve as primary or assisted energy storage solutions [Figure 14]. As primary energy storage components, FSSCs offer high power density, allowing for rapid charging-discharging cycles. This makes them suitable for applications requiring quick bursts of energy, such as fitness trackers or smart textiles. In an assisted energy storage role, these supercapacitors can complement traditional batteries by providing additional energy during peak demand or extending battery life. For instance, in wearable health monitors, FSSCs can store and release energy to power sensors and data transmission modules during high-activity periods.

Figure 14. The application of supercapacitors in electric vehicles as assistant energy storage. Reproduced with permission[179].

Furthermore, integrating FSSCs with batteries can enhance overall performance. The supercapacitors handle high power demands and quick recharges, while the batteries provide longer-lasting energy storage. This combination ensures that wearable devices remain operational for extended periods without frequent recharging. By leveraging the strengths of both supercapacitors and batteries, hybrid systems offer a balanced solution for the diverse energy needs of wearable technology.

Power supply

FSSCs are well-suited for acting as power supplies in various wearable products due to their flexibility and high-power output. As for wearable electronics, such as smartwatches, fitness bands, and health monitors, these supercapacitors can be embedded into the framework of the devices, providing a compact and flexible power source that conforms to the user’s body. This integration offers an unobtrusive power supply solution that enhances user comfort and device functionality.

For on-body power supply applications, FSSCs integrated into clothing or accessories can reduce the need for bulky external batteries. For instance, smart jackets embedded with supercapacitors can power LEDs, heating elements, or communication devices, offering a seamless and efficient power solution[180]. Additionally, these supercapacitors can be applied in energy harvesting systems by storing energy from ambient sources, such as body movements or solar cells integrated into wearables [Figure 15][181,182].

The versatility and adaptability of FSSCs make them an ideal choice for wearable technology, providing reliable and efficient energy storage and power supply solutions that cater to the dynamic requirements of modern wearable devices.

Sensor medium

FSSCs offer a unique advantage in wearable technology: they can function not only as energy storage and power supply units but also as sensor media [Figure 16A]. This dual functionality stems from their high surface area and conductivity, making them ideal for sensitive and accurate electrochemical measurements[183,184].

Figure 16. (A) Schematic illustration showing the FSSCs for wearable sensor integration application. Reproduced with permission[187]; (B) The self-powered sensor with FSSCs composed of silk-based conductive composite fibers (CNFA@ESF). Reproduced with permission[188]; (C) Applications of FSSCs as a real-time sensor to measure the linear strain. Reproduced with permission[190]. FSSCs: Fiber-shaped supercapacitors.

However, the sensing performance of FSSCs can vary significantly depending on the choice of materials and structural configurations. For fiber-type electrode-based stress or strain sensors and capacitor modules, their structures are mainly coaxial spiral-wound and coaxial wrapped. Such a design allows the two electrodes of the supercapacitor to be separated, and then the outer wrapped electrode or the inner wound electrode can act as a sensing response layer. When subjected to external stress, the sensitive material in the electrode (for example, based on porous cotton thread or polymer doped with graphene, CNTs, MXene and other conductive materials) changes its structural state, resulting in resistance changes, or the resistance changes due to the compression between the spiral structures from the original separated state to a continuous state.

For example, a recent study introduced an all-yarn-based TENG-ASC sensor, constructed by wrapping a cylindrical, yarn-structured ASC with a helically wound, sheath-core TPU/carbon black (CB)@silver nanowire (AgNW)/polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) yarn. The ASC, which utilizes AgNW/MnO2-TPU and AgNW/AC-TPU layers, achieves a volumetric energy density of 3.2 mWh cm-3 and demonstrates impressive cycle stability, withstanding over 10,000 cycles. As a proof of concept, this device effectively gathers and stores biomechanical energy, allowing the supercapacitor to charge repeatedly and power a red LED light. When subjected to pressure or bending, the spiral-wound elastic yarn layer compresses, bringing AgNW-coated surfaces into contact and triggering conductivity by altering the device’s resistance. By tracking these resistance or current changes under different pressure levels, the sensor precisely measures applied force and deformation. With a sensitivity of 30.3 kPa-1 and detection range of up to 50 kPa, this compact design shows strong potential for wearable applications in smart textiles, combining efficient energy harvesting, storage, and pressure sensing in a single device[185]. For another example, an all-hydrogel yarn-based supercapacitor was developed to merge energy storage and sensing capabilities in wearable textiles. This device utilizes a sodium dodecyl sulfate-modified polyvinyl alcohol @ copoly (acrylate-aniline) hydrogel yarn, which offers high mechanical durability and flexibility with 300% elongation at break and tensile strength of 1 MPa. To enhance pressure sensitivity and mechanical resilience, the supercapacitor is wrapped in a soft, fluffy rGCF (RGO-modified cotton fibers) film. This film provides cushioning, protects the supercapacitor surface, and achieves a sensitivity of 25.75 kPa-1 over a pressure range of up to 44 kPa[186]. This all-hydrogel supercapacitor-sensor exemplifies the integration of energy storage with sensitive pressure detection in a comfortable, durable format suitable for wearable bioelectronics.

In addition, FSSCs can be designed to detect biomolecules such as glucose in sweat, enabling real-time health monitoring or functioning as temperature sensors[187-190]. They can also monitor environmental conditions such as pH levels, offering valuable diagnostic information. This integration of sensing capabilities with energy storage in a single fiber streamlines the design of wearable devices. Imagine a single fiber simultaneously storing energy and measuring temperature or pressure, eliminating the need for separate components and leading to more compact and efficient wearable systems [Figure 16A]. Chen et al.[188] developed a self-powered sensor using silk-based conductive composite fibers that combines energy storage and sensing [Figure 16B]. The CNFA@ESF (a stiff gel-protected flexible self-powered sensor based on

Other potential application

Medical health and sports

In implantable devices for electronic medical, FSSCs could serve as compact, flexible power sources that enhance patient comfort compared to conventional rigid batteries. By providing reliable, long-lasting power, they reduce the need for frequent battery replacement surgeries, which are costly and pose health risks. For example, in the field of special medical wearables such as Pacemakers, Cochlear Implant, Neurostimulator, etc., there are higher requirements for power density and long cycle life[191-193], where the applied battery is still a major problem, and supercapacitors are expected to obtain potential applications in this area.

Moreover, FSSCs have been explored as components in self-powered circuits for medical implants[194], helping to collect and store energy from the body's movements or external sources, further extending device lifespans[195,196]. In sports, fitness, and orientation, textile supercapacitors support wearable devices that monitor physiological responses and locations during physical activity, providing valuable data to both users and medical personnel[197,198]. This innovation was successfully applied to diagnose sleep

Pulsed power application

FSSCs have significant potential in pulsed power applications, where high power output and rapid energy release are required. Due to their ability to deliver short, high-power bursts, FSSCs can serve in applications where a quick discharge of energy is essential for replacing the traditional rigid, bulky non-flexible overcapacity[199,200].

For military and defense, FSSCs could provide the rapid energy discharge required for systems such as radar, railguns, and directed energy weapons. Their compact, flexible structure also makes them suitable for powering medical imaging and diagnostic devices, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and portable ultrasound systems, where brief but intense energy pulses enhance performance. In renewable energy systems, FSSCs can stabilize energy output by capturing and releasing power in bursts to manage fluctuations, especially in solar and wind energy setups[201-203]. Additionally, their pulsed power capability benefits wireless communication devices by providing intermittent high-energy bursts for data transmission over long distances or in challenging environments, such as in remote sensing or satellite communication[204,205]. Lastly, FSSCs can support industrial applications that require explosive actuation, such as pyrotechnics in mining or specialized manufacturing processes, by providing quick, high-power pulses essential for triggering small-scale explosions or mechanical movements. These diverse applications illustrate the adaptability of FSSCs for pulsed power needs across multiple industries.

Applications in extreme environments

As wearable and portable electronics expand into challenging environments, there is an increasing demand for energy storage solutions that are lightweight, flexible, and resilient under extreme conditions[206-208]. FSSCs stand out in this regard, combining high power density and fast charging capabilities with adaptability to various shapes and stresses. Unlike traditional batteries, which often struggle under temperature fluctuations, high pressure, or mechanical impacts, FSSCs can be engineered to maintain stable performance across a range of harsh environments. This versatility has opened up multiple application areas for FSSCs in extreme settings.

Under these conditions, applications in the field of aerospace and space exploration can be envisaged. FSSCs withstand drastic temperature changes and high radiation levels, making them ideal for powering devices in satellites, spacesuits, and spacecraft. Similarly, for deep-sea exploration, these supercapacitors can be designed with protective coatings to resist high pressures and corrosive saltwater, enabling reliable energy storage in underwater vehicles and equipment. In desert and high-temperature operations, FSSCs maintain performance under intense heat and solar exposure, supporting wearable electronics and autonomous devices in arid regions. Altogether, the durability, flexibility, and adaptability of FSSCs offer robust solutions for energy storage in environments where other power sources may falter.

As the demand for wearable electronics and sustainable energy solutions continues to grow, the environmental impact of FSSC materials and their fabrication methods becomes an increasingly important consideration. While FSSCs offer significant advantages in terms of flexibility, energy storage, and integration with wearable devices, their environmental footprint-spanning material sourcing, production, and end-of-life disposal-requires further attention.

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT AND SUSTAINABILITY

Recyclability of FSSC materials

Many of the materials used in FSSCs, such as CNTs, graphene, and various conductive polymers, have shown potential for recyclability[209,210]. For instance, CNTs and graphene can be recovered and reused in subsequent cycles, contributing to a reduction in waste. However, challenges remain in the efficient recovery of these materials, especially in complex composites. Research is underway to develop closed-loop recycling systems, particularly for graphene-based and polymer-based FSSCs, to minimize material loss during the device’s lifecycle.

Environmental costs of material sourcing

The extraction and synthesis of materials such as CNTs, MXenes, and certain conductive polymers can have significant environmental costs. For example, CNT production often involves energy-intensive processes, and the extraction of raw materials such as rare earth metals can lead to environmental degradation if not properly managed[78]. MXene production often requires the use of highly corrosive acids such as hydrofluoric acid and other solvents[211]. On the other hand, more sustainable alternatives are emerging, such as bio-based polymers and bio-sourced materials that could replace traditional synthetic components, reducing the environmental footprint of these devices.

Sustainable manufacturing practices

To mitigate the environmental impact of FSSC production, green manufacturing practices are gaining attention. These practices focus on reducing energy consumption, minimizing waste, and using renewable or less toxic solvents in the fabrication of FSSCs. For example, solvent-free processing methods and the use of environmentally friendly materials are being explored to make the production of FSSCs more sustainable. Additionally, advancements in 3D printing and roll-to-roll manufacturing techniques[212] promise to streamline the production of FSSCs while reducing material waste and energy use.

Future directions

As the field of FSSCs evolves, addressing the current challenges such as energy density, safety, and integration with wearable electronics will be crucial for advancing their practical applications. To enhance energy density, future research could focus on developing novel electrode materials, such as

Safety concerns related to FSSCs, particularly regarding their thermal stability and flammability, can be addressed through the development of non-toxic, flame-retardant materials, and the use of encapsulation techniques that enhance thermal regulation. Advances in self-healing materials and protective coatings could also extend the lifespan and reliability of these devices, minimizing the need for maintenance in

Furthermore, the integration of FSSCs into electronics remains a significant challenge. Future research could focus on improving material compatibility and developing scalable manufacturing processes to ensure seamless integration with flexible electronic components. This would enable more reliable and efficient power delivery for wearable devices. The incorporation of conductive adhesives, advanced interconnects, and scalable fabrication techniques, such as 3D printing, will likely facilitate the mass production of wearable electronics with integrated energy storage solutions.

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

FSSCs have emerged as a transformative technology in the realm of flexible electronics, offering remarkable potential for energy storage in portable and smart devices. While challenges remain, continued advancements in material science, fabrication techniques, and device integration are expected to drive significant improvements in performance, scalability, and practical applicability.

Key conclusions from this exploration underscore the versatility of FSSCs in fabrication techniques, enhanced performance, and broad-ranging applications. Methods such as wet spinning, electrospinning, and 3D printing have proven effective for precise and scalable production, while innovative designs, such as multilayer structures and integrated approaches, further enhance the functionality of these supercapacitors. The development of advanced materials, including nanomaterials and conductive polymers, has significantly improved their energy density, power density, and mechanical flexibility, making them highly suitable for wearable electronics, smart textiles, and portable devices.

Looking ahead, several critical areas require focused research to further advance the development of FSSCs for wearable and portable electronics. One major challenge is enhancing the stretchability and mechanical durability of these devices, as they need to maintain high performance under significant deformation, especially in applications that involve frequent motion. To address this, future research should focus on improving the stretchability of FSSC materials while ensuring their mechanical resilience. Another important aspect is the integration of self-healing materials into FSSCs, which would extend the lifespan and reliability of wearable devices, allowing them to recover from mechanical damage and minimizing maintenance costs. In addition, FSSCs must be optimized for environmental resilience, as wearable devices are exposed to harsh conditions such as moisture, temperature fluctuations, and mechanical wear. Research into materials that can perform consistently under extreme conditions will be crucial for broadening the usability of these devices. Furthermore, integration with renewable energy sources, such as embedding solar cells into textiles, could lead to self-powered systems that increase the sustainability of wearables and portable electronics. Finally, as the demand for these devices grows, addressing the environmental impact of FSSC production will become increasingly important. Future studies should focus on developing

Despite these challenges, the future of FSSCs is promising, with ongoing research aimed at improving performance, scalability, and integration with renewable energy sources. As fabrication methods improve and environmental concerns are addressed, FSSCs will play an increasingly pivotal role in the development of next-generation wearable electronics, smart textiles, and health-monitoring systems. These innovations will contribute to a new era of flexible, efficient, and sustainable energy storage solutions.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Data collection and writing: Zhou, X.; Li, G.; Dong, X.; Xi, W.; Jiang, Y.

Conceptualization, writing, and supervision: Zhou, X.; Zheng, X.

Review, supervision, and funding: Zheng, X.; Li, L.; Yuan, N.; Ding, J.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the Major Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) for Basic Theory and Key Technology of Tri-Co Robots (92248301), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52303051), Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2308085ME146, 2008085QE213), Changzhou Sci & Tech Program (Grant No. CJ20235019), and Educational Commission of Anhui Province of China (2024AH030005).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Iqbal, S. M. A.; Mahgoub, I.; Du, E.; Leavitt, M. A.; Asghar, W. Advances in healthcare wearable devices. npj. Flex. Electron. 2021, 5, 107.

2. Babu, M.; Lautman, Z.; Lin, X.; Sobota, M. H. B.; Snyder, M. P. Wearable devices: implications for precision medicine and the future of health care. Annu. Rev. Med. 2024, 75, 401-15.

3. Yan, Z.; Luo, S.; Li, Q.; Wu, Z. S.; Liu, S. F. Recent advances in flexible wearable supercapacitors: properties, fabrication, and applications. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2302172.

4. He, J.; Cao, L.; Cui, J.; et al. Flexible energy storage devices to power the future. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2306090.

5. He, A.; He, J.; Cao, L.; et al. Flexible supercapacitor integrated systems. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2024, 9, 2301931.

6. Zhang, Y.; Mei, H.; Cao, Y.; et al. Recent advances and challenges of electrode materials for flexible supercapacitors. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 438, 213910.

7. Benzigar, M. R.; Dasireddy, V. D. B. C.; Guan, X.; Wu, T.; Liu, G. Advances on emerging materials for flexible supercapacitors: current trends and beyond. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2002993.

8. Zhou, X.; Xu, J.; Zhu, W.; et al. A new laminated structure for electrodes to boost the rate performance of long linear supercapacitors. Mater. Lett. 2017, 204, 177-80.

9. Kim, J.; Yu, H.; Jung, J. Y.; et al. 3D architecturing strategy on the utmost carbon nanotube fiber for ultra-high performance fiber-shaped supercapacitor. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2113057.

10. Xu, P.; Gu, T.; Cao, Z.; et al. Carbon nanotube fiber based stretchable wire-shaped supercapacitors. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2014, 4, 1300759.

11. Yang, Z.; Deng, J.; Chen, X.; Ren, J.; Peng, H. A highly stretchable, fiber-shaped supercapacitor. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 13453-7.

12. Shi, P.; Li, L.; Hua, L.; et al. Design of amorphous manganese oxide@multiwalled carbon nanotube fiber for robust solid-state supercapacitor. ACS. Nano. 2017, 11, 444-52.

13. Yu, H.; Kim, J.; Lee, D.; et al. Active material-free continuous carbon nanotube fibers with unprecedented enhancement of physicochemical properties for fiber-type solid-state supercapacitors. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2024, 14, 2303003.

14. Cheng, H.; Li, Q.; Zhu, L.; Chen, S. Graphene fiber-based wearable supercapacitors: recent advances in design, construction, and application. Small. Methods. 2021, 5, e2100502.

15. Hu, Y.; Cheng, H.; Zhao, F.; et al. All-in-one graphene fiber supercapacitor. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 6448-51.

16. Yu, J.; Wang, M.; Xu, P.; et al. Ultrahigh-rate wire-shaped supercapacitor based on graphene fiber. Carbon 2017, 119, 332-8.

17. Qu, G.; Cheng, J.; Li, X.; et al. A Fiber supercapacitor with high energy density based on hollow graphene/conducting polymer fiber electrode. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 3646-52.

19. Zhai, S.; Jiang, W.; Wei, L.; et al. All-carbon solid-state yarn supercapacitors from activated carbon and carbon fibers for smart textiles. Mater. Horiz. 2015, 2, 598-605.

20. Lin, J.; Ko, T.; Lin, Y.; Pan, C. Various treated conditions to prepare porous activated carbon fiber for application in supercapacitor electrodes. Energy. Fuels. 2009, 23, 4668-77.

21. Su, C.; Wang, C.; Lu, K.; Shih, W. Evaluation of activated carbon fiber applied in supercapacitor electrodes. Fibers. Polym. 2014, 15, 1708-14.

22. Jin, Z.; Yan, X.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, G. Sustainable activated carbon fibers from liquefied wood with controllable porosity for high-performance supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2014, 2, 11706-15.

23. Chi, G.; Gong, W.; Xiao, G.; et al. Wire-shaped, all-solid-state, high-performance flexible asymmetric supercapacitors based on (Mn,Fe) oxides/reduced graphene oxide/oxidized carbon nanotube fiber hybrid electrodes. Nano. Energy. 2023, 117, 108887.

24. Chen, X.; Paul, R.; Dai, L. Carbon-based supercapacitors for efficient energy storage. Nat. Scie. Rev. 2017, 4, 453-89.

25. Sharma, P.; Bhatti, T. A review on electrochemical double-layer capacitors. Energy. Convers. Manag. 2010, 51, 2901-12.

26. Frackowiak, E.; Jurewicz, K.; Delpeux, S.; Béguin, F. Nanotubular materials for supercapacitors. J. Power. Sources. 2001, 97-98, 822-5.

27. Shih, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, C.; Lin, J.; Huang, C. The electrosorption characteristics of simple aqueous ions on loofah-derived activated carbon decorated with manganese dioxide polymorphs: the effect of pseudocapacitance and beyond. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 425, 130606.

28. Chatterjee, D. P.; Nandi, A. K. A review on the recent advances in hybrid supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2021, 9, 15880-918.

29. Jäckel, N.; Simon, P.; Gogotsi, Y.; Presser, V. Increase in capacitance by subnanometer pores in carbon. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2016, 1, 1262-5.

30. Chmiola, J.; Yushin, G.; Dash, R.; Gogotsi, Y. Effect of pore size and surface area of carbide derived carbons on specific capacitance. J. Power. Sources. 2006, 158, 765-72.

31. Barbieri, O.; Hahn, M.; Herzog, A.; Kötz, R. Capacitance limits of high surface area activated carbons for double layer capacitors. Carbon 2005, 43, 1303-10.

32. Raza, W.; Ali, F.; Raza, N.; et al. Recent advancements in supercapacitor technology. Nano. Energy. 2018, 52, 441-73.

33. Augustyn, V.; Simon, P.; Dunn, B. Pseudocapacitive oxide materials for high-rate electrochemical energy storage. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 1597.

34. Zhu, X. Recent advances of transition metal oxides and chalcogenides in pseudo-capacitors and hybrid capacitors: a review of structures, synthetic strategies, and mechanism studies. J. Energy. Storage. 2022, 49, 104148.

35. Deng, L.; Wang, Z.; Cui, H.; et al. Mechanistic understanding of the underlying energy storage mechanism of α-MnO2-based pseudo-supercapacitors. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2408476.