Selective photooxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural in water enabled by highly dispersed gold nanoparticles on graphitic carbon nitride

Abstract

Photocatalytic synthesis of chemicals is highly recognized for its eco-friendliness and mild reaction conditions, yet it faces considerable challenges regarding catalytic efficiency, stability and cost. The selective photooxidation of

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Lignocellulosic biomass constitutes the most abundant renewable carbon resource on our planet and stands at the forefront of sustainable energy and chemical production[1,2]. With an ever-transforming global energy landscape and a growing emphasis on environmental sustainability, the efficient conversion of biomass into valuable chemicals has become a critical area of focus within scientific research and industrial development[3-5]. One such endeavor involves the catalytic transformation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF), a versatile platform molecule derived from biomass, into 2,5-diformylfuran (DFF)[6,7]. This is a

The photocatalytic selective oxidation of HMF to DFF represents a significant advancement in the field, offering a pathway to more efficient and environmental benign processes[8]. This approach not only addresses the scientific challenges associated with selective oxidation but also aligns with the commercial potential for manufacturing high-performance materials and chemicals. By integrating cutting-edge photocatalytic techniques with a deep understanding of the underlying reaction mechanisms, this work aims to pave the way for innovative applications in catalytic science and sustainable chemistry, as supported by a comprehensive review[8,9] of the literature and our experimental findings[10-15].

The oxidation of HMF remains a significant challenge in the chemical industry because traditional processes often rely on hazardous oxidants and harsh reaction conditions[16,17]. Alternatively, photocatalytic oxidation of HMF has emerged as a green and low-power approach, being capable of harvesting solar energy under mild conditions[8,18,19]. In this context, graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) can distinguish itself as a premier photocatalyst due to its unique electronic structure, optimal bandgap (ca. 2.7 eV) and exceptional stability[20]. These features allow collective enhancement of light absorption and photocatalytic efficiency across the visible spectrum. The superiority of g-C3N4 is underscored by its selectivity in generating singlet oxygen (1O2) over the indiscriminate hydroxyl radical (·OH), thereby mitigating unexpected over-oxidation of target molecules[21]. However, the intrinsic activity of g-C3N4 is limited due to the low utilization of visible light and the recombination of photogenerated electrons (e-) and holes (h+).

Despite its promising properties, optimizing g-C3N4 for enhanced photocatalytic performance necessitates addressing the efficiency of charge-carrier separation and transport. Thus, many efforts have been made through structural modification, element doping, heterojunction construction, and co-catalyst integration[20]. However, the reported superior separation and transfer of photogenerated charge carriers must use harmful organic solvents like trifluoromethylbenzene[22]. Therefore, the demand for greener synthetic protocols calls for environmentally friendly solvents, especially the cleanest water solvents. In the literature, thermal exfoliation[23] and H2O2 complexation[24-26] have been tried to improve the catalytic performances of g-C3N4 for photooxidation of HMF to DFF in the aqueous phase, but the obtained catalytic efficiencies are dissatisfying. As a result, new strategy is still needed to significantly boost the g-C3N4 catalysis for this target reaction.

Metal nanocatalysts with visible-light response and localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) have received widespread attention[27]. Plasmonic metal nanostructures have the capacity to augment the

Herein, this work is devoted to improving the pristine photocatalytic efficiency of g-C3N4 by in situ deposition of Au nanoparticles so as to create the LSPR effect. The origin of different catalytic results, which depend on the g-C3N4 morphology and Au size, is unraveled. This innovative strategy can bolster not only the catalyst response to visible light but also its selectivity toward DFF. Furthermore, this study delves into the real reactive oxygen species, the interfacial electron transfer processes, and reaction mechanism of this photocatalytic system. This work also reveals for the first time the relationship between the energy of photogenerated e- obtained from the LSPR effect of noble-metal nanoparticles and their ability to migrate to semiconductors. This can provide a valuable reference for future research on plasmonic metal/g-C3N4 type photocatalysts.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Urea (99.5%), dicyandiamide (99%) and gold (III) chloride trihydrate (99.9%, Au 50%) from Innochem, and methanol (AR, 99.5%) and melamine (99%) from Aladdin were used for catalyst preparation. HMF (98%), DFF (98%), 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furoic acid (HMFCA, 98%), 5-formyl-2-furoic acid (FFCA, 98%) and

Catalyst preparation

The overall synthetic method was described in Supplementary Scheme 1. g-C3N4 was prepared with three different precursors by high-temperature calcination. In a typical procedure, urea, dicyandiamide or melamine was placed in a ceramic crucible with the lid to ensure a certain degree of sealing. The calcination was carried out from room temperature to 550 °C (2 °C min-1) and maintained for 4 h. The solids were then cooled naturally to room temperature and ground for 30 min. The so-obtained g-C3N4 carrier was named CN(I), CN(II) and CN(III), respectively.

g-C3N4 supported Au catalyst (loading: 1 wt%) was prepared using photodeposition method. Typically,

Catalyst characterizations

Physical characterizations

Inductively-coupled-plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) was carried out using an Agilent 7500a apparatus. Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed on a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer by utilizing Cu Kα radiation at a beam voltage of 40 kV. The diffraction pattern was scanned with a rate of

Photoelectrochemical characterizations

The photoelectrochemical (PEC) performance of catalyst was assessed using an AutoLab electrochemical workstation, model PGSTAT302N within a standard three-electrode configuration. The working electrode comprised Indium tin oxide (ITO) glass coated with the catalyst, a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) functioned as the reference, and a platinum wire served as the counter electrode. To prepare the working electrode, 5 mg of the catalyst was dispersed with 0.5 mL of ethanol, to which 10 μL of Nafion® solution was added, followed by 2 h of sonication. To prepare the thin-film electrode, 10 μL of the mixture was finely applied onto ITO glass with an area of 0.25 cm2, followed by drying at room temperature for 30 min. The PEC measurement was conducted at 25 °C under a 300 W Xe lamp with a Na2SO4 electrolyte solution

Catalyst evaluation

As illustrated in Supplementary Scheme 2, the aqueous phase aerobic oxidation of HMF to DFF was conducted under atmospheric pressure at a fixed temperature of 35 °C in a quartz reactor. Typically, HMF (0.1 mmol), catalyst (30 mg) and deionized water (100 mL) were mixed into the reactor, which was then subjected to an ultrasonic treatment at 40 kHz for 15 min to ensure complete dissolution and dispersion, followed by stirring in the dark at 500 rpm for an additional 15 min to achieve desorption equilibrium between the catalyst and the reactant.

For the photochemical reaction, a Xe lamp (CEL-HXF300-T3 provided by Beijing China Education Au-light Technology Co., Ltd.) emitting light in the range of 350-780 nm at an intensity of 0.75 W cm-2 was used. The Xe lamp was placed vertically 6 cm above the liquid surface and the reactor was connected to a thermostat water at 35 °C and an O2 flow of 10 mL min-1. The continuous sampling with 0.5 mL aliquots was conducted every 15 min. The quantitative analysis was carried out on an Agilent 1260 Infinity HPLC system using external standard method and diluted H2SO4 solution (5 mmol L-1) as mobile phase. The photodiode array detector (DAD) and the Shodex SH-1011 sugar column (8 mm, 300 mm, 6 µm) were configured. The specific wavelengths were set for detecting HMF (285 nm), DFF/FFCA (290 nm), and HMFCA/FDCA

Density functional theory calculations

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)[34]. The elemental core and valence electrons were represented by the projector augmented wave (PAW) method and plane-wave basis functions with a cut-off energy of 500 eV. For all the calculations, generalized gradient approximation with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (GGA-PBE) exchange-correlation functional was employed. The DFT-D3 empirical correction method was used to describe van der Waals interactions. Monkhorst-Pack k-points of 2 × 2× 1 were applied. All structures were optimized without constraint with a force tolerance of 0.02 eV Å-1. The g-C3N4 model was built according to the literature[35]. For the Au/CN(I) catalyst, ten Au atoms were stacked on the (111) crystal plane above the (001) crystal plane of the g-C3N4 model.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

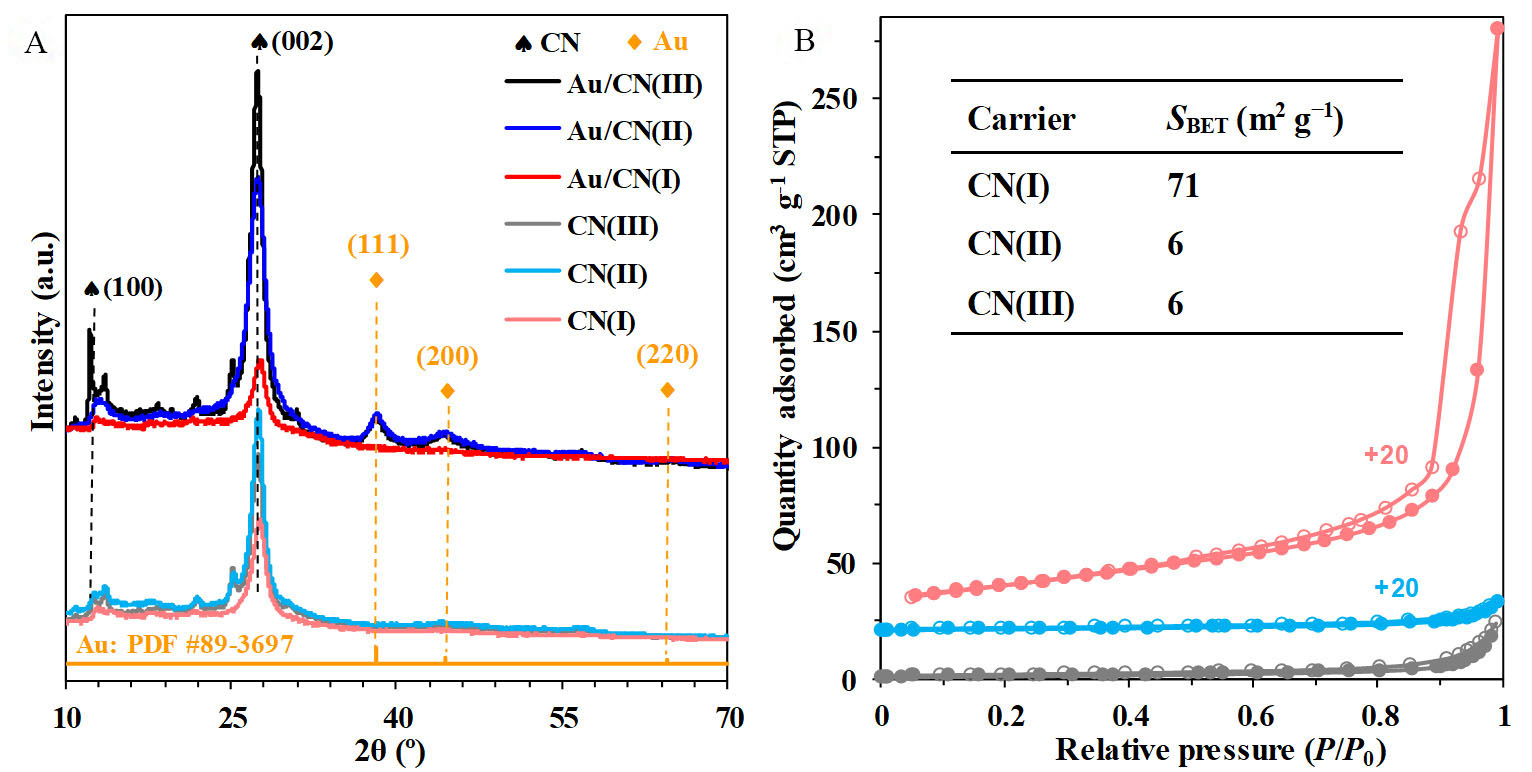

Firstly, the Au content of the catalyst was determined by ICP-MS. The precise loadings are all around 1 wt% [Supplementary Table 1], showing the effective immobilization of Au onto carriers. The composition and phase structure of the as-synthesized catalytic materials were later examined by XRD. Figure 1A illustrates a typical XRD pattern due to g-C3N4 for all the solids. The characteristic peaks at 13.1° and 27.5° correspond to the (100) and (002) planes of g-C3N4, which results from the interlayer stacking of the conjugated aromatic system[36]. This observation verifies the successful construction of analogous g-C3N4 structure by even using different organic precursors through calcination. In addition, Figure 1A shows new diffraction peaks at 38.3°, 44.4° and 64.6° for Au/CN(II) and Au/CN(III), which can be attributed to the (111), (200) and (220) planes of Au (PDF #89-3697)[32]. The mean Au size calculated by the Scherrer equation is approximately 6.7 and 7.5 nm [Supplementary Table 1], respectively. However, these typical Au peaks are not detected on the Au/CN(I) catalyst, which could originate from the highly dispersed Au particles with small sizes. This interesting phenomenon indicates that the properties of different g-C3N4 carriers can affect the particle size of supported Au.

Figure 1. (A) XRD patterns of g-C3N4 carriers and supported Au catalysts; (B) N2 isothermal curves and pore size distribution of g-C3N4 carriers. XRD: rowder X-ray diffraction.

Afterward, the porosity of the bare carriers was analyzed by N2 adsorption-desorption. As depicted in Figure 1B, all the g-C3N4 carriers display type-IV isotherms but only CN(I) presents an obvious type-H3 hysteresis loop at a high P/P0 of 0.6-0.9. This isothermal feature usually reflects irregular mesoporous structure due to the stacking of layered materials[37]. As a result, CN(I) exhibits a much higher specific surface area of 71 m2 g-1, reaching ca. 12 folds over that of CN(II) and CN(III) (6 m2 g-1). This significant difference in surface area can be responsible for the high dispersion of Au nanoparticles on the CN(I) carrier. As is well known, carbon nitride materials are constructed on melem units, specifically pyrolysis of urea, dicyandiamide and melamine to melem requires three-step, two-step and one-step thermal polymerization, respectively[36]. Therefore, the polymerization degree of the as-prepared g-C3N4 carriers from the three precursors is CN(I) < CN(II) < CN(III)[23]. As a result, the different polymerization degrees of g-C3N4 due to various building blocks can decide the final morphology.

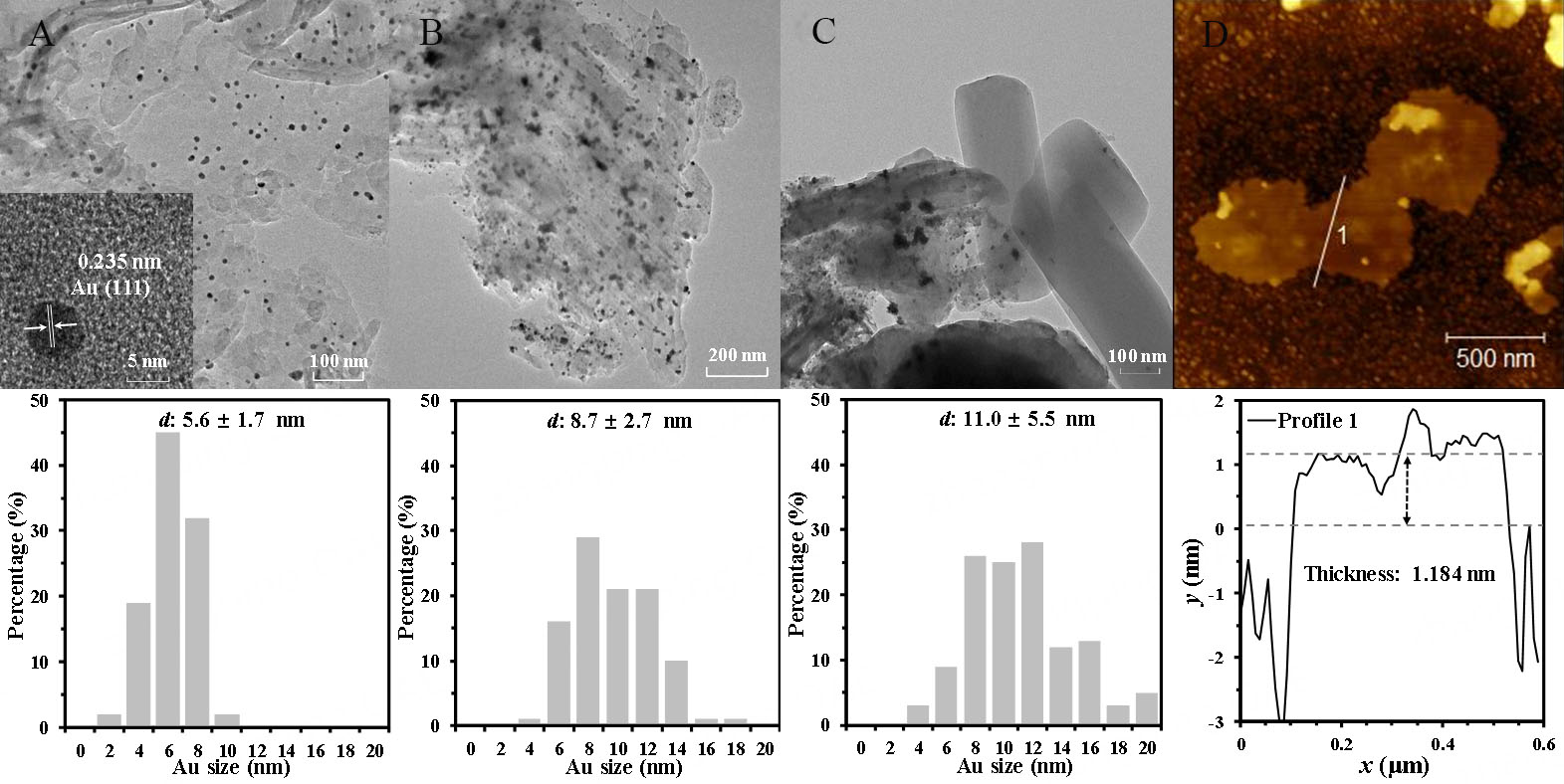

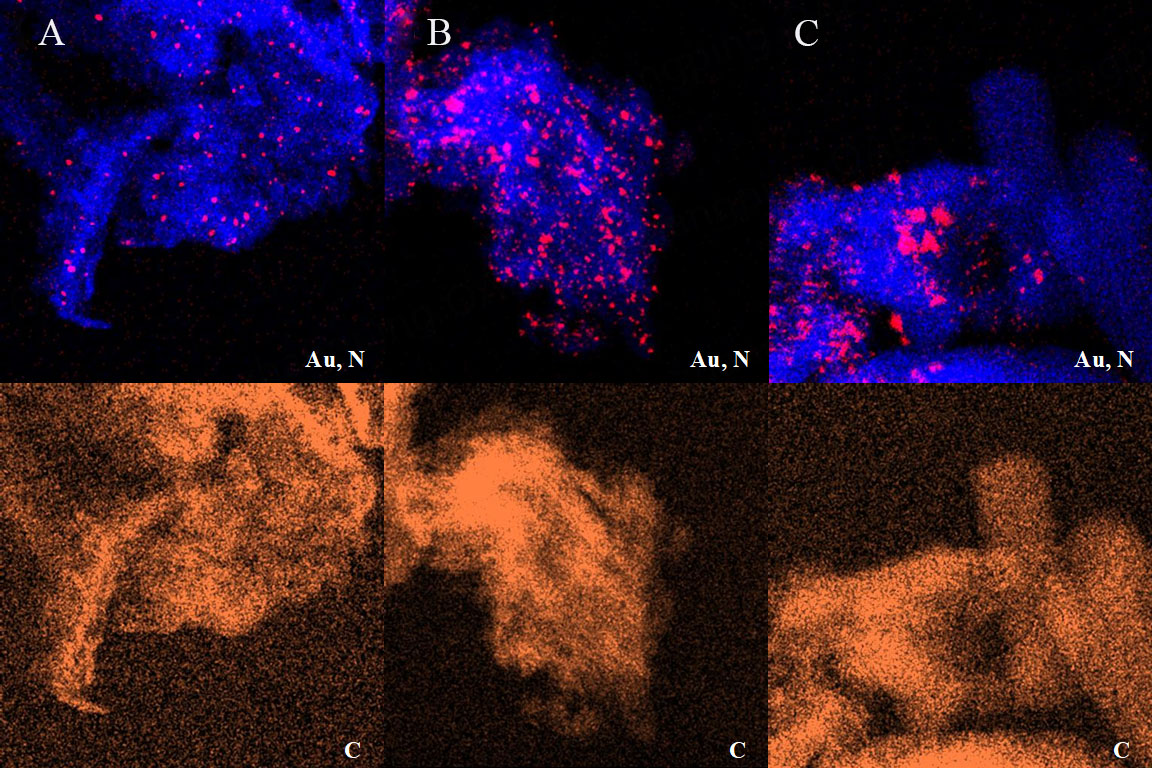

Following that, the morphology of the Au catalyst was further inspected by TEM, AFM, and EDS. The TEM images reveal the distinct structural features of Au nanoparticles loaded on different g-C3N4 carriers. Specifically, CN(I) obtained through urea pyrolysis displays a single-layered flake-like structure [Figure 2A], while CN(II) derived from dicyandiamide pyrolysis presents a multi-layered structure with flake-like stacking [Figure 2B]. However, CN(III) resultant from melamine pyrolysis mainly exhibits nanorod-like structure [Figure 2C]. Moreover, the supported Au nanoparticles are found to continuously grow bigger and become aggregated. The average sizes of Au are estimated to be ca. 5.6, 8.7 and 11 nm for the Au/CN(I), Au/CN(II) and Au/CN(III) catalysts, respectively. These values are similar to the Au sizes measured by the XRD technique. Notably, AFM measurement further proves the single-layered flake structure of CN(I) [Figure 2D]. This feature allows effective dispersing of Au nanoparticles onto the large surface of CN(I), giving uniform and small Au sizes. On the contrary, the multi-layered nanosheet and nanorod structures with extremely small surface areas would eventually result in embedding and aggregating of Au nanoparticles on CN(II) and CN(III). A high-resolution TEM image confirms the formation of Au crystals. The interplanar spacing of 0.235 nm can be identified to be the (111) plane of cubic Au[38]. Furthermore, EDS analysis clearly visualizes the elemental composition and distribution. The uniform overlapping of C and N elements substantiates the successful synthesis of carbon nitride [Figure 3]. The Au sizes and particle dispersions on g-C3N4 are very well coincident with XRD and TEM results.

Figure 2. TEM images and the estimated size distribution of Au nanoparticles for the (A) Au/CN(I); (B) Au/CN(II), and (C) Au/CN(III) catalysts; (D) AFM image and analysis of Au/CN(I). TEM: transmission electron microscopy; AFM: an atomic force microscope.

Figure 3. Color-coded elemental maps of Au from the M line, N from the K line and C from the K line for the (A) Au/CN(I); (B) Au/CN(II), and (C) Au/CN(III) catalysts.

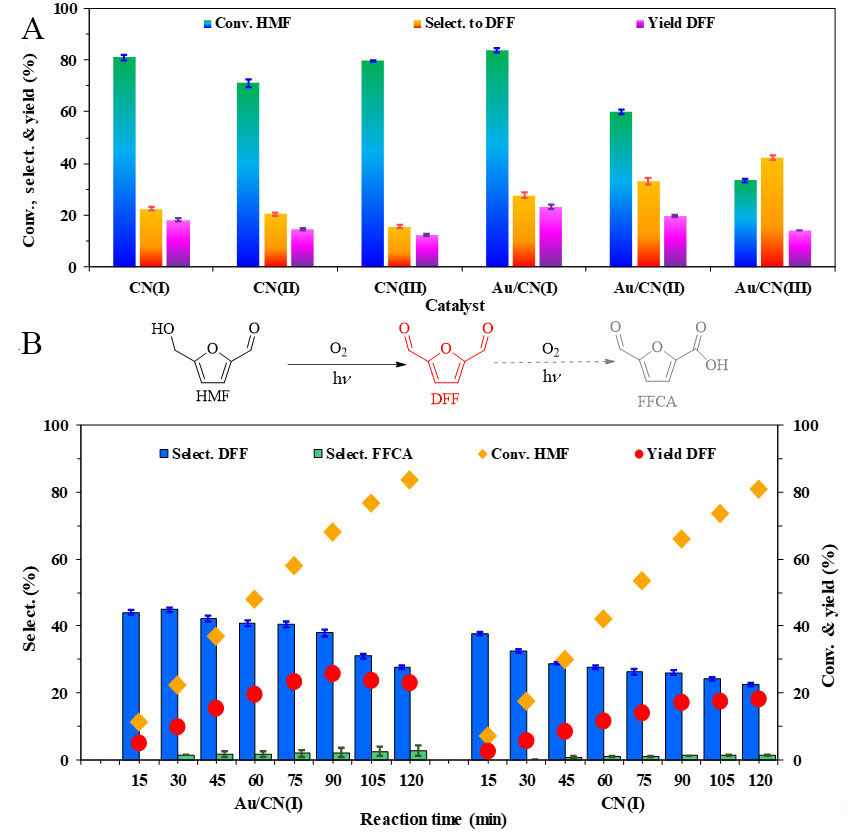

The visible-light-driven photocatalytic oxidation of HMF to DFF was first investigated using different

Figure 4. (A) Catalytic performances of g-C3N4 carriers and supported Au catalysts for photooxidation of HMF to DFF; (B) Time-course investigation of CN(I) and Au/CN(I) during photooxidation of HMF. Reaction conditions: HMF, 0.1 mmol; catalyst, 30 mg; deionized water, 100 mL; O2 flow, 10 mL min-1; Xe lamp, l = 350-780 nm; temperature, 35 °C; time, 2 h for (A). HMF: 5-hydroxymethylfurfural; DFF: 2,5-diformylfuran.

Thereafter, the evolution of HMF conversion and product selectivity was compared between CN(I) and

In order to compare the catalyst efficiency among different g-C3N4-based catalysts in the literature, the productivity of DFF defined as mgDFF gcatal.-1 h-1 for a catalyst was calculated to quantify the activity of g-C3N4 for producing DFF in a unit time. As summarized in Table 1, the present Au/CN(I) catalyst demonstrates a 26% yield of DFF, placing it among the top catalysts working in the aqueous phase. More importantly, the productivity of DFF over the Au/CN(I) catalyst reaches as high as 72.7 mgDFF gcatal.-1 h-1, being the most active catalyst reported in the literature to date. This outstanding efficiency has surpassed over three times the highly active benchmark catalysts, i.e., polymeric carbon nitride obtained by thermal etching and adducted with hydrogen peroxide (MCN-TE-H2O2, 21.6 mgDFFgcatal.-1 h-1)[26] and g-C3N4 derived from melamine and thermally exfoliated at 540 °C for 4 h [g-C3N4 (MCN), 22.9 mgDFFgcatal.-1 h-1][23]. Besides, the Au/CN(I) catalyst can even outperform the classic

Comparison of catalytic performances of g-C3N4-based catalysts for photooxidation of HMF to DFF in water under simulated sunlight

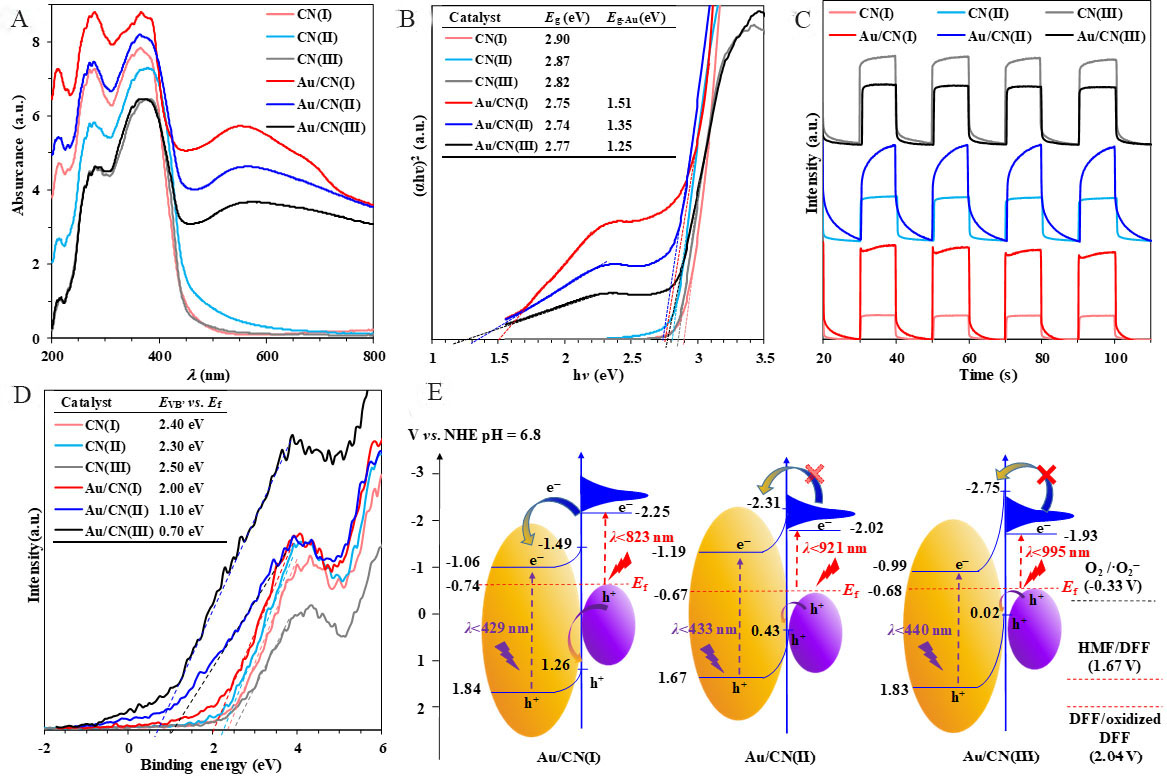

To delve deeper into the remarkable boost in photocatalytic activity conferred by the interfacial interactions between Au nanoparticles and g-C3N4, a series of characterizations were performed. UV-vis DRS was first employed to scrutinize the light absorption capability of solids. Figure 5A illustrates that different g-C3N4 carriers can absorb light in the partial visible and ultraviolet regions and CN(I) exhibits the most robust absorption. This absorption capability can be obviously improved by dispersing small-sized Au nanoparticles onto g-C3N4. Notably, the absorption of visible light is greatly enhanced on Au/CN(I). This phenomenon has been largely attributed to the LSPR of Au nanoparticles in the literature[27].

Figure 5. (A) UV-vis DRS; (B) Tauc plot; (C) photocurrent and (D) VB-XPS of g-C3N4 carriers and supported Au catalysts; (E) Schematic diagram of the band structure of the Au/CN(I), Au/CN(II), and Au/CN(III) catalysts. XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy.

Then, the bandgap energy (Eg) of the catalyst was extracted from the Tauc plot. As shown in Figure 5B,

Afterward, photocurrent measurement was conducted to assess the ability of a catalyst to provide photogenerated electrons after light absorption. As expected, Figure 5C shows a notable increase in photocurrent intensity for the CN(I) and CN(II) carriers with the presence of Au nanoparticles. On the contrary, a decreased photocurrent is obviously recorded on the Au/CN(III) catalyst compared to CN(III). This abnormal phenomenon may explain the sharp decline in HMF conversion on CN(III) due to Au deposition.

As is known to all, the strength of oxidation capability of a photocatalyst is intricately tied to its valence band position. Following that, valence band (VB)-XPS and Mott-Schottky analysis were used to investigate this important property[10]. As displayed in Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 3, all the solids present positive slope curves, which are characteristic of n-type semiconductor behavior. The

As displayed in Figure 5A, there is an inverse relationship between supported-Au size and visible-light response. This correlation can be attributed to the enhanced LSPR effect that occurs with decreasing metal particle size. Furthermore, Figure 5E illustrates that the energy barrier at the Schottky junction, which is formed by the bending of the energy bands upon the combination of a semiconductor and a metal, also diminishes as the Au size decreases. Consequently, the reduced size of Au nanoparticles facilitates the mobility of photogenerated e- through LSPR effect, crossing the energy barrier of the Schottky junction. Such an ease of traversal can promote the migration of those photogenerated e-.

Based on the above results, Figure 5E illustrates that the energy of photogenerated electrons excited by the LSPR effect on the Au/CN(I) catalyst can significantly exceed the Schottky barrier[28]. In contrast, the energies for the Au/CN(II) and Au/CN(III) catalysts fall short with the latter being substantially insufficient. As a consequence, the Au/CN(I) catalyst enables swift migration and separation of photogenerated e- and h+ between the metal and semiconductor. However, the Au/CN(III) catalyst fails to achieve this separation process, which eventually culminates in a reduced photocurrent intensity.

As shown in Supplementary Figure 3A, CN(I) demonstrates the lowest fluorescence intensity relative to CN(II) and CN(III), which means the minimal recombination rate of photogenerated e- and h+ for the CN(I) catalyst. After photodeposition of Au nanoparticles, the photoresponse intensity of CN(I) obviously increases but the fluorescence intensity further decreases. This clearly illustrates that Au nanoparticles can enhance the separation of photogenerated charge carriers. Furthermore, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) experiments show declining impedances for all g-C3N4 carriers after introducing Au

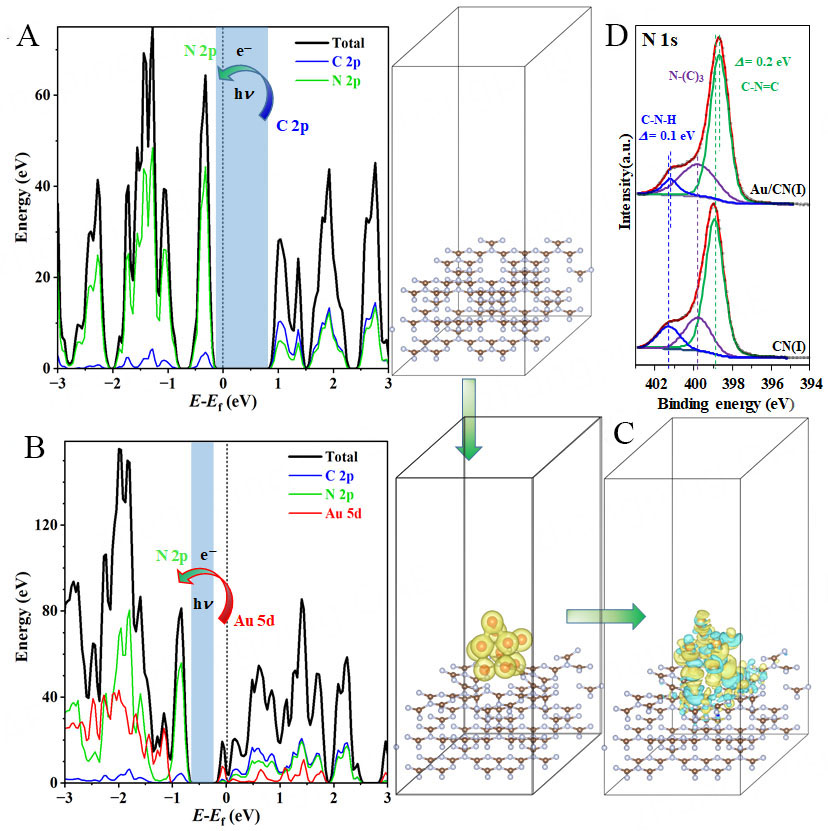

To further elucidate the electron transfer and band structure alteration between Au nanoparticles and the CN(I) carrier, DFT calculations were executed. Figure 6A and B illustrates that the valence band maximum and conduction band minimum of CN(I) are mainly constituted by the 2p orbitals of C and N. Under light exposure, the electron transition from the C 2p to the N 2p orbitals enables the generation of photoinduced e- and h+. The incorporation of Au nanoparticles notably narrows the bandgap and the valence band maximum is found predominantly by contribution of the 5d orbital of Au. This result indicates that electrons upon absorbing photon energy can move from the Au 5d orbital to the N 2p orbital within the Au/CN(I) catalyst.

Figure 6. PDOS of the (A) CN(I) carrier and (B) Au/CN(I) catalyst; (C) Differential charge density distribution of Au/CN(I); (D) XPS spectra of N 1s core level of CN(I) and Au/CN(I). XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy.

Moreover, differential charge density distribution calculations were used for verifying the electron transfer. As shown in Figure 6C, yellow and green patterns represent the electron-sufficient and electro-deficient regions, respectively. The scheme clearly illustrates electron transfer from CN(I) to Au. XPS analysis discloses the presence of predominant Au species in a metallic state on the surface of Au/CN(I) catalyst

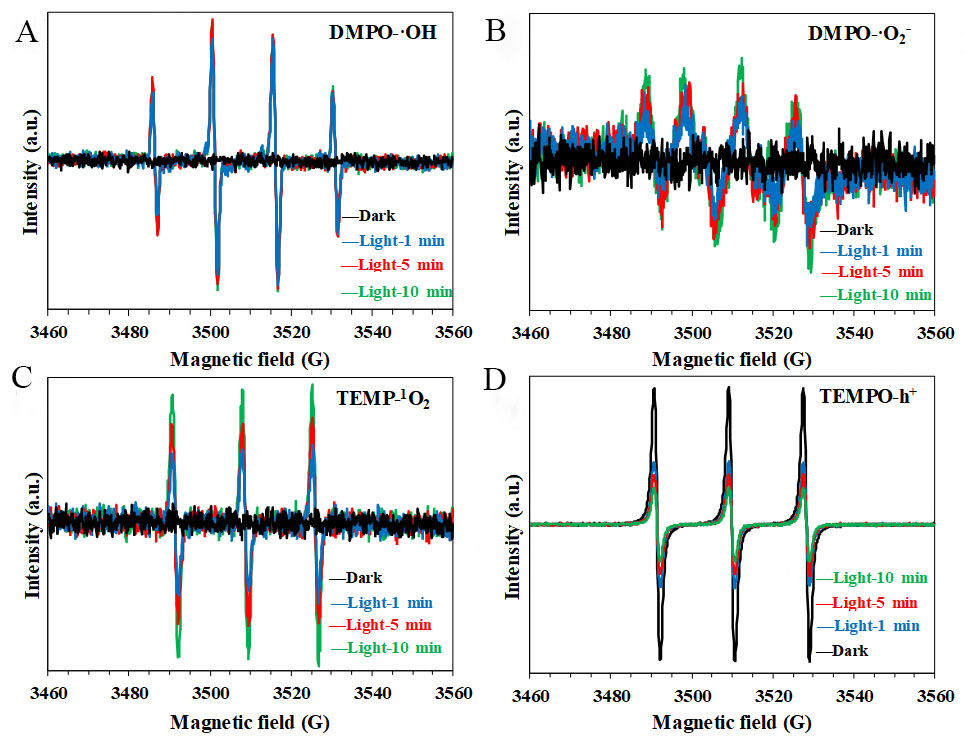

The generation and transformation of reactive oxygen species are pivotal in photocatalytic oxidation reactions[41]. To identify the short-lived free radical intermediates in the reaction process, in situ EPR measurements were conducted. Typically, 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-piperidinol (DMPO) is used as radical scavenger for hydroxyl radical (•OH) and superoxide anion (•O2-)[10] In addition, 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine (TEMP)[42] and

Figure 7. EPR in situ signals of (A) DMPO-·OH; (B) DMPO-·O2-; (C) TEMP-1O2, and (D) TEMPO-h+ species during photooxidation of HMF with Au/CN(I) and water, except methanol for (B). EPR: electron paramagnetic resonance; DMPO: 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-piperidinol; TEMP: 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine; TEMPO: 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy; HMF: 5-hydroxymethylfurfural; EPR: electron paramagnetic resonance.

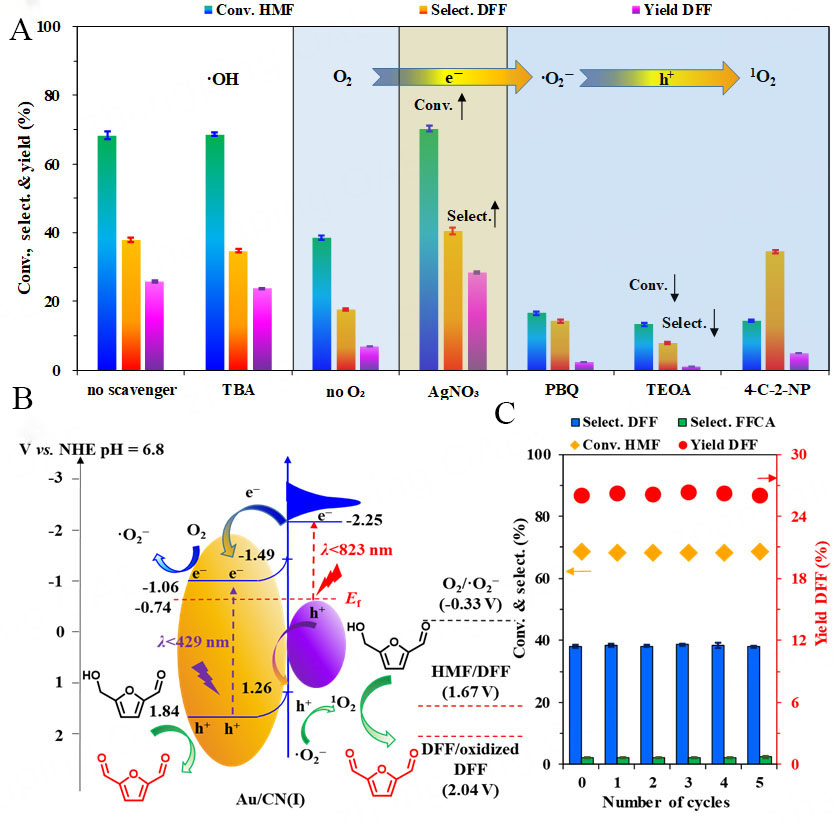

Furthermore, the radical quenching experiments were carried out to understand the roles of different reactive oxygen species in determining activity and selectivity of the Au/CN(I) catalyst for HMF photooxidation. Typically, AgNO3[44], benzoquinone (PBQ), triethanolamine (TEOA),

After elucidation of the modification of band structure and the roles of different oxygen species, the plausible reaction mechanism of Au/CN(I)-catalyzed photooxidation of HMF to DFF can be discussed. As proposed in Figure 8B, highly dispersed Au nanoparticles with small sizes on CN(I) can give rise to electron transfer from Au to N, which causes the band bending and the formation of Schottky junction. The LSPR effect of Au nanoparticles enables the enhanced absorption of visible light, which allows excited electrons to overcome the Schottky barrier and move to the conduction band of CN(I). Owing to the more negative conduction band position than the O2/•O2- reduction potential, the photogenerated e- can reduce and activate O2 to form •O2-. This process is followed by oxidation of •O2- into 1O2 by h+. Then, 1O2 can selectively oxidize HMF to DFF. In addition, the valence band position of CN(I) is found to situate between the oxidation potentials required for HMF to DFF and DFF to byproducts. This band structure allows h+ to directly oxidize HMF to DFF, too[10].

Figure 8. (A) Catalytic results of controlled experiments over the Au/CN(I) catalyst by adding different scavengers during photooxidation of HMF to DFF; (B) Plausible reaction mechanism of the photocatalytic oxidation of HMF to DFF using the Au/CN(I) catalyst; (C) Recycling test of the Au/CN(I) catalyst. Reaction conditions: HMF, 0.1 mmol; scavenger, 0.1 mmol; catalyst, 30 mg; deionized water, 100 mL; O2 flow, 10 mL min-1; Xe lamp, l = 350-780 nm; temperature, 35 °C; time, 1.5 h. HMF:

The stability and reusability of a heterogeneous catalyst are highly favored by potential industrial applications. Thereby, these crucial metrics of the Au/CN(I) photocatalyst were rigorously tested. The used catalyst was separated via filtration, thoroughly washed with ethanol and deionized water, and subsequently dried in an oven at 80 °C overnight. Figure 8C exhibits that the catalyst can maintain consistent performance across five successive cycles with minimal variations in HMF conversion and DFF selectivity. ICP-MS analysis of the post-reaction solution reveals the absence of Au component leached from the solid catalyst, validating the robust anchoring of Au by photodeposition on CN(I). TEM and XPS analyses further show the well preserved structure and morphology of this catalyst after reuses [Supplementary Figure 7]. These results can highlight the remarkable stability of Au/CN(I) photocatalysts.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, highly-dispersed and small-sized Au nanoparticles deposited on g-C3N4 were shown as highly efficient photocatalysts for aerobic oxidation of HMF to DFF in water. The CN(I) carrier obtained by urea pyrolysis was disclosed to have a large specific surface area and a single-layered flake structure. The smaller Au nanoparticles (ca. 5.6 nm) enabled the strongest response of the catalyst for visible light. Moreover, Au nanoparticles on CN(I) excited by the LSPR effect allowed the generation of photoelectrons with sufficient energy to surpass the Schottky barrier. As a result, efficient separation and transfer of photogenerated e- and h+ were realized, leading to the highest productivity of DFF among benchmark catalysts. Furthermore, this study validated the generation and transformation of different reactive species during photocatalytic oxidation and identified h+ and 1O2 as catalytic active sites for the selective conversion of HMF to DFF. The cogenerated H2O2 as a byproduct via oxidation of HMF by •O2- radical can further oxidize DFF and even result in mineralization reaction. This work demonstrated for the first time the influence of relationship between LSPR effect and Schottky barrier on photocurrent and catalytic activity.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, methodology, formal analysis, writing - original draft preparation:

Investigation, formal analysis: Fan B, Wang Y

Supervision, resources, funding acquisition: Gu B, Tang Q, Qiu F, Cao Q

Conceptualization, supervision, writing - review and editing, project administration, funding acquisition: Fang W

Availability of data and materials

Experimental details and supporting data can be found in Supplementary Materials. Other raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22272149, 22062025), the Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (Nos. 202201AU070095, 202301AT070169, 202401AV070020), the Yunnan University's Research Innovation Fund for Graduate Students (No. KC-23234000), and the Open Research Fund of School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering of Henan Normal University.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Deng, W.; Wang, Y. Research perspectives for catalytic valorization of biomass. J. Energy. Chem. 2023, 78, 102-4.

2. Deng, W.; Feng, Y.; Fu, J.; et al. Catalytic conversion of lignocellulosic biomass into chemicals and fuels. Green. Energy. Environ. 2023, 8, 10-114.

3. Li, Y.; Zhang, D.; Qiao, W.; et al. Nanostructured heterogeneous photocatalyst materials for green synthesis of valuable chemicals. Chem. Synth. 2022, 2, 9.

4. Wen, H.; Zhang, W.; Fan, Z.; Chen, Z. Recent advances in furfural reduction via electro- and photocatalysis: from mechanism to catalyst design. ACS. Catal. 2023, 13, 15263-89.

5. Wu, X.; Li, J.; Xie, S.; et al. Selectivity control in photocatalytic valorization of biomass-derived platform compounds by surface engineering of titanium oxide. Chem 2020, 6, 3038-53.

6. Chen, S.; Wojcieszak, R.; Dumeignil, F.; Marceau, E.; Royer, S. How catalysts and experimental conditions determine the selective hydroconversion of furfural and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 11023-117.

7. Zhang, W.; Qian, H.; Hou, Q.; Ju, M. The functional and synergetic optimization of the thermal-catalytic system for the selective oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-diformylfuran: a review. Green. Chem. 2023, 25, 893-914.

8. Zhang, Q.; Gu, B.; Fang, W. Sunlight-driven photocatalytic conversion of furfural and its derivatives. Green. Chem. 2024, 26, 6261-88.

9. Wu, X.; Luo, N.; Xie, S.; et al. Photocatalytic transformations of lignocellulosic biomass into chemicals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 6198-223.

10. Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Gu, B.; Tang, Q.; Cao, Q.; Fang, W. Sunlight-driven photocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural over a cuprous oxide-anatase heterostructure in aqueous phase. Appl. Catal. B. 2023, 320, 122006.

11. Wang, Y.; Gao, T.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Q.; Fang, W. Efficient hydrogenation of furfural to furfuryl alcohol by magnetically recoverable RuCo bimetallic catalyst. Green. Energy. Environ. 2022, 7, 275-87.

12. Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Synergy in magnetic NixCo1Oy oxides enables base-free selective oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural on loaded Au nanoparticles. J. Energy. Chem. 2023, 78, 526-36.

13. Zhang, H.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, W.; et al. Base-free selective oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural over Pt nanoparticles on surface Nb-enriched Co-Nb oxide. Appl Catal B 2023;330:122670.

14. Zhang, H.; Gao, T.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Synergistic catalysis in loaded PtRu alloy nanoparticles to boost base-free aerobic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Mater. Today. Catal. 2023, 3, 100013.

15. Fan, B.; Zhang, H.; Gu, B.; Qiu, F.; Cao, Q.; Fang, W. Constructing Pr-doped CoOOH catalytic sites for efficient electrooxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. J. Energy. Chem. 2025, 100, 234-44.

16. Lilga, M. A.; Hallen, R. T.; Gray, M. Production of oxidized derivatives of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF). Top. Catal. 2010, 53, 1264-9.

17. Deurzen MP, van Rantwijk F, Sheldon RA. Chloroperoxidase-catalyzed oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 1997, 16, 299-309.

18. Xia, T.; Gong, W.; Chen, Y.; et al. Sunlight-driven highly selective catalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural towards tunable products. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2022, 61, e202204225.

19. Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, L.; et al. In situ fabrication Ti3C2Fx MXene/CdIn2S4 schottky junction for photocatalytic oxidation of HMF to DFF under visible light. Appl. Catal. B. 2023, 330, 122635.

20. Ismael, M.; Shang, Q.; Yue, J.; Wark, M. Photooxidation of biomass for sustainable chemicals and hydrogen production on graphitic carbon nitride-based materials: a comprehensive review. Mater. Today. Sustain. 2024, 27, 100827.

21. Akhundi, A.; García-lópez, E. I.; Marcì, G.; Habibi-yangjeh, A.; Palmisano, L. Comparison between preparative methodologies of nanostructured carbon nitride and their use as selective photocatalysts in water suspension. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2017, 43, 5153-68.

22. Wang, X.; Meng, S.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, X.; Chen, S. 2D/2D MXene/g-C3N4 for photocatalytic selective oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural into 2,5-formylfuran. Catal. Commun. 2020, 147, 106152.

23. Krivtsov, I.; García-lópez, E. I.; Marcì, G.; et al. Selective photocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furfural to 2,5-furandicarboxyaldehyde in aqueous suspension of g-C3N4. Appl. Catal. B. 2017, 204, 430-9.

24. Ilkaeva, M.; Krivtsov, I.; García, J. R.; et al. Selective photocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furfural in aqueous suspension of polymeric carbon nitride and its adduct with H2O2 in a solar pilot plant. Catal. Today. 2018, 315, 138-48.

25. Ilkaeva, M.; Krivtsov, I.; García-lópez, E.; et al. Selective photocatalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxaldehyde by polymeric carbon nitride-hydrogen peroxide adduct. J. Catal. 2018, 359, 212-22.

26. Marcì, G.; García-lópez, E.; Pomilla, F.; et al. Photoelectrochemical and EPR features of polymeric C3N4 and O-modified C3N4 employed for selective photocatalytic oxidation of alcohols to aldehydes. Catal. Today. 2019, 328, 21-8.

27. Mao, Q.; Ma, J.; Chen, M.; Lin, S.; Razzaq, N.; Cui, J. Recent advances in heavily doped plasmonic copper chalcogenides: from synthesis to biological application. Chem. Synth. 2023, 3, 26.

28. Lee, S.; Lee, S. W.; Jeon, T.; Park, D. H.; Jung, S. C.; Jang, J. Efficient direct electron transfer via band alignment in hybrid metal-semiconductor nanostructures toward enhanced photocatalysts. Nano. Energy. 2019, 63, 103841.

29. Furube, A.; Du, L.; Hara, K.; Katoh, R.; Tachiya, M. Ultrafast plasmon-induced electron transfer from gold nanodots into TiO2 nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 14852-3.

30. Fowler, R. H. The analysis of photoelectric sensitivity curves for clean metals at various temperatures. Phys. Rev. 1931, 38, 45-56.

31. Liu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Cullen, D. A.; Xie, Z.; Lian, T. Efficient hot electron transfer from small Au nanoparticles. Nano. Lett. 2020, 20, 4322-9.

32. Yang, Q.; Wang, T.; Han, F.; Zheng, Z.; Xing, B.; Li, B. Bimetal-modified g-C3N4 photocatalyst for promoting hydrogen production coupled with selective oxidation of biomass derivative. J. Alloys. Compd. 2022, 897, 163177.

33. Ghalta, R.; Srivastava, R. Photocatalytic selective conversion of furfural to γ-butyrolactone through tetrahydrofurfuryl alcohol intermediates over Pd NP decorated g-C3N4. Sustain. Energ. Fuels. 2023, 7, 1707-23.

34. Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comp. Mater. Sci. 1996, 6, 15-50.

35. Xiong, T.; Cen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, F. Bridging the g-C3N4 interlayers for enhanced photocatalysis. ACS. Catal. 2016, 6, 2462-72.

36. Wang, X.; Maeda, K.; Thomas, A.; et al. A metal-free polymeric photocatalyst for hydrogen production from water under visible light. Nat. Mater. 2009, 8, 76-80.

37. Fang, W.; Fan, Z.; Shi, H.; et al. Aquivion®-carbon composites via hydrothermal carbonization: amphiphilic catalysts for solvent-free biphasic acetalization. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2016, 4, 4380-5.

38. Wu, S.; Shang, R.; Zhang, H.; et al. Steering the Au-FexCo1Oy interface for efficient imine synthesis at low temperature via oxidative coupling reaction. Mol. Catal. 2023, 547, 113292.

39. García-lópez, E. I.; Pomilla, F. R.; Bloise, E.; et al. C3N4 impregnated with porphyrins as heterogeneous photocatalysts for the selective oxidation of 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furfural under solar irradiation. Top. Catal. 2021, 64, 758-71.

40. Movahed, S. K.; Miraghaee, S.; Dabiri, M. AuPd alloy nanoparticles decorated graphitic carbon nitride as an excellent photocatalyst for the visible-light-enhanced Suzuki-miyaura cross-coupling reaction. J. Alloys. Compd. 2020, 819, 152994.

41. Lu, G.; Chu, F.; Huang, X.; Li, Y.; Liang, K.; Wang, G. Recent advances in metal-organic frameworks-based materials for photocatalytic selective oxidation. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 450, 214240.

42. Xu, S.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Selective oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid using O2 and a photocatalyst of Co-thioporphyrazine bonded to g-C3N4. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 14775-82.

43. Peng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, G.; Tian, Y.; Ma, D.; Zhang, Y. Novel p-n heterojunctions incorporating NiS1.03@C with nitrogen doped TiO2 for enhancing visible-light photocatalytic performance towards cyclohexane oxidation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 566, 150676.

44. Yang, M. Q.; Zhang, N.; Xu, Y. J. Synthesis of fullerene-, carbon nanotube-, and graphene-TiO2 nanocomposite photocatalysts for selective oxidation: a comparative study. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interf. 2013, 5, 1156-64.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Author Biographies

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].