Assessing life satisfaction, self-harm, and suicidal thoughts in transgender women following genital gender-affirming surgery

Abstract

Aim: Gender dysphoria causes significant psychological distress in individuals, leading many to seek medical interventions, including hormone therapy and gender-affirming surgery (GAS). This study sought to enhance the understanding of life satisfaction and self-harm and suicidal thoughts among transgender women after genital GAS.

Methods: A retrospective cohort of 102 transgender women who underwent GAS during 2011-2021 at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, with a follow-up period of at least 1 year after genital GAS, was studied. Data were collected as part of a larger initiative that focused on transgender women. The participants were surveyed using the Life Satisfaction Questionnaire, Gender Congruence and Life Satisfaction Scale, and a general demographic health survey. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results: Of the 98 eligible participants, 50 completed the questionnaire. Although 28% of the respondents experienced thoughts of self-harm or suicidal ideation postoperatively, they reported overall satisfaction with life and mental health, suggesting that surgical treatment may have had a positive impact on life satisfaction and gender congruence.

Conclusion: Our study highlights the significant issues of thoughts of self-harm or suicidal ideation among transgender women after genital GAS. Although the prevalence thereof was lower than that reported previously, it remains concerning. Nevertheless, most participants reported life satisfaction and finding life meaningful post-surgery. These findings emphasize the need for integrating continuous mental health support with access to GAS to address the mental health challenges of transgender women after genital GAS, while aiming to improve the quality of life as the primary goal.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Sweden has one of the world’s longest-standing traditions of providing subsidized gender-confirming medical procedures for individuals with trans experiences[1]. The National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden permits patients diagnosed with gender dysphoria (GD) to receive gender affirmation treatment[2]. This multidisciplinary treatment includes conversational support, gender-affirming surgery (GAS), hormone therapy, voice therapy, and hair removal[2,3]. GAS is classified as highly specialized national care[4,5], which ensures more equitable care, greater patient benefit, and secured accessibility for a growing patient group[4-6]. In Sweden, requests for transgender procedures have increased, with a threefold increase in Gothenburg from 2013 to 2017[7].

Genital surgery is recommended only after meeting specific criteria, including documented GD, legal age, informed consent, controlled medical or mental health concerns, 12 months of hormone therapy, and living in a congruent sex role for at least 12 months[8]. These treatments aim to ensure comfort with one’s gender, improve psychological well-being, and achieve self-fulfillment[9,10].

The largest health survey among transgender persons in Sweden, conducted by Folkhälsomyndigheten, found that 36% of respondents had thought about or attempted suicide in the past year, with higher rates among younger individuals, before surgery[11]. This is a markedly higher rate than the 3% of individuals aged 16 years and older in the general Swedish population who reported having considered taking their own lives at some point during the past year[12]. Similarly, numerous international studies have concluded that transgender individuals experience significantly higher rates of suicidal ideation and attempts, as well as a higher prevalence of mental health issues[13-15]. A US study revealed significant disparities in mental health outcomes between transgender individuals and the general population. Forty percent of transgender people have attempted suicide at some point in their lives, compared to 4.6% of the general US population[16]. For completeness purposes, Table 1 shows the prevalence of suicidal ideations in patients across various medical conditions, diagnosis, and social populations[17-23]. Moreover, 48% of transgender individuals reported experiencing suicidal thoughts during the 12 months preceding the survey, compared to 4% of the general population, and 7% had attempted suicide, in contrast to 0.6% of the general population[16]. Additionally, a Canadian review showed that 55% of transgender individuals reported having had suicidal thoughts, with 29% attempting suicide during their lifetime[24]. Similarly, a review in India confirmed that transgender people are at a higher suicide risk compared to the general population[25].

Prevalence of suicidal ideation across various medical conditions, diagnosis, and social populations

| Description | Suicidal ideation |

| Obesity | 3.2%-4.3%[17] |

| Schizophrenia | 34.5%[18] |

| Cancer | 0.27%-53.3%[19] |

| Anxiety disorders | 10%-53%[20] |

| Burn injuries | 1%-43%[21] |

| Chronic pain | 7.9%-40.9%[22] |

| Homeless people | 41.6%[23] |

| Transgender people US | 48%[16] |

| General population US | 4%[16] |

| Transgender people SWE | 36%*[12] |

| General population SWE | 3%[12] |

Risk factors for suicide include previous suicide attempts, a family history of suicidal behavior, and mental illnesses, such as mood disorders and schizophrenia[26]. Other factors include impulsivity, anxiety, major stress events, substance abuse involving alcohol or opioids, and chronic pain. Individuals with a history of abuse or trauma, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and those identified as LGBTQ+ are also at higher risk[26]. In particular, transgender individuals face higher risks of anxiety, depression, and substance abuse due to discrimination, stigma, and a lack of healthcare access[27,28]. Affective disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, are more common than psychotic disorders among the transgender population[29,30]. Moreover, autism rates are higher among people with GD, and they experience significantly more social anxiety and depressive symptoms[31]. Consequently, transgender individuals, who often experience multiple concurrent risk factors, face an enhanced overall risk of suicide and suicidal thoughts.

Improvements in mental health and quality of life (QoL) in transgender patients following vaginoplasty are well-documented[32-36]. Studies have suggested that GAS, such as vaginoplasty, can significantly enhance the mental well-being and overall QoL of transgender individuals[9].

METHODS

Study design and participants

This retrospective survey was conducted at the Sahlgrenska University Hospital and included patients who underwent gender-affirming surgeries between 2011 and 2021. This study formed part of a larger data collection initiative that focuses on transgender women who have undergone GAS. Of the 108 patients living in Sweden who were initially considered, 102 met the inclusion criteria of having at least 1 year of follow-up post-surgery.

Data collection

Of the 102 recruited participants, four were lost to follow-up due to missing or outdated addresses and were thus excluded from the study, leaving 98 patients who received the survey questionnaire via post mail. Since all the patients who were assigned to the male gender at birth and who underwent genital GAS were followed up by a network of psychologists in Sweden, we are aware that none of the recruited participants had committed suicide by the time of submission of this manuscript.

Of the 98 patients who received the questionnaire, 50 patients returned a completed questionnaire between October 2020 and November 2022. Among the completed questionnaires, some questions were left unanswered in some instances. Table 2 illustrates the flow of participants throughout the study. Table 3 details the questionnaires used.

Details of participant engagement and response rates

| Description | Number |

| Considered participants | 108 |

| Met inclusion criteria | 102 |

| Lost to follow-up | 4 |

| Questionnaires distributed | 98 |

| Respondents | 50 |

Overview of the questionnaires used

| Code | Description |

| Q1 | LiSat-11 - Life Satisfaction Questionnaire |

| Q2 | GCLS - Gender Congruence and Life Satisfaction Scale |

| Q3 | Demographic Health Survey |

Participants were surveyed using the Life Satisfaction Questionnaire (LiSat-11)[37,38], Gender Congruence and Life Satisfaction Scale (GCLS)[39], and a general Demographic Health Survey to obtain basic demographic information and health data.

Statistical analysis

This cross-sectional analysis focused on a selection of questions from the GCLS, LiSat-11, and Demographic Health Survey to provide targeted insights into thoughts of self-harm, suicidal ideation, and QoL in transgender women following GAS. Descriptive statistics were performed using SPSS software (version 29; IBM Inc., Armonk, NY, USA) to analyze the data collected from the questionnaires.

Ethics and consent

Ethical approval was obtained from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority, application number 2020-03062. To protect patient anonymity, individuals were assigned codes prior to the questionnaire distribution. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants to ensure adherence to the ethical standards for research involving human subjects.

RESULTS

Response rate and participant characteristics

The study achieved a response rate of 51%, with 50 of 98 patients completing the questionnaire postoperatively. Participants had diverse educational backgrounds and employment statuses [Table 4]. Of the 50 respondents, 32% had undergone vaginal reoperation. Regarding other diagnoses, 72% had mental illness, 28% had a neuropsychiatric diagnosis, and 28% reported having no such diagnosis.

Background variables

| Background variables | Number (n) | Percent (%) |

| Education level | n = 45 | |

| - High school | 22 | 49 |

| - Vocational education | 3 | 7 |

| - University degree | 20 | 44 |

| Employment status | n = 48 | |

| - Employed | 35 | 73 |

| - Unemployed/On sick leave | 8 | 17 |

| - Retired | 5 | 10 |

| Re-operated vaginally | n = 50 | |

| - Yes | 16 | 32 |

| - No | 34 | 68 |

| Other diagnosis | n = 50 | |

| - Mental illness | 36 | 72 |

| - Neuropsychiatric diagnosis | 14* | 28 |

| - No diagnosis | 14 | 28 |

At the time of follow-up, all patients had undergone surgery between three and eight years prior, with an even distribution over this six-year period. The surgical techniques used were either penile inversion vaginoplasty or vulvoplasty (i.e., without cavity creation). Each patient received the specific procedure they had requested during the preoperative consultations. Two patients in this series developed rectovaginal fistulas postoperatively and subsequently underwent revision surgery with bowel vaginoplasty.

Life satisfaction

Responses to the LiSat-11 questionnaire revealed that none of the participants were “very unsatisfied” with “Life as a whole,” with an average life satisfaction score of 4.5 on a 6-point scale. This finding suggests a moderate general sense of satisfaction across the cohort. Figure 1 displays the levels of life satisfaction among participants, showing a predominance of moderate to high satisfaction.

Patient enjoyment of life

Participants were asked to respond to an item, “I have not enjoyed life,” on the GLCS. Almost half reported that they had never felt this way, whereas less than one-third reported that they rarely felt this way. Figure 2 shows the frequency with which the participants did not enjoy life, with the majority indicating that they usually enjoyed life.

Mental health status

Psychological health assessment by the LiSat-11 showed that more than one-third of the participants were not satisfied with their psychological health [Figure 3]. In contrast, about two-thirds of participants reported feeling satisfied to various degrees. Figure 3 shows the distribution of psychological health status, highlighting both satisfaction and dissatisfaction among the surveyed individuals.

Experiences of meaninglessness

In Figure 4, the responses to a GCLS item on the meaninglessness of life are shown. More than half of respondents indicated that they did not feel that their lives were meaningless. Others occasionally or frequently experienced such feelings, reflecting the emotional challenges they faced after surgery. Only one participant felt that her life was meaningless. Thus, the majority of respondents indicated that they had never felt that their lives were meaningless.

Mood fluctuations

Investigations into mood fluctuations using the GCLS showed that more than two-thirds of respondents infrequently or never experienced low mood, whereas about one-third reported more frequent occurrences of low mood [Figure 5]. This variability underscores the range of emotional responses following surgical intervention. Figure 5 demonstrates the spectrum of low mood among respondents, which varied from never to often, but with no constant low mood reported.

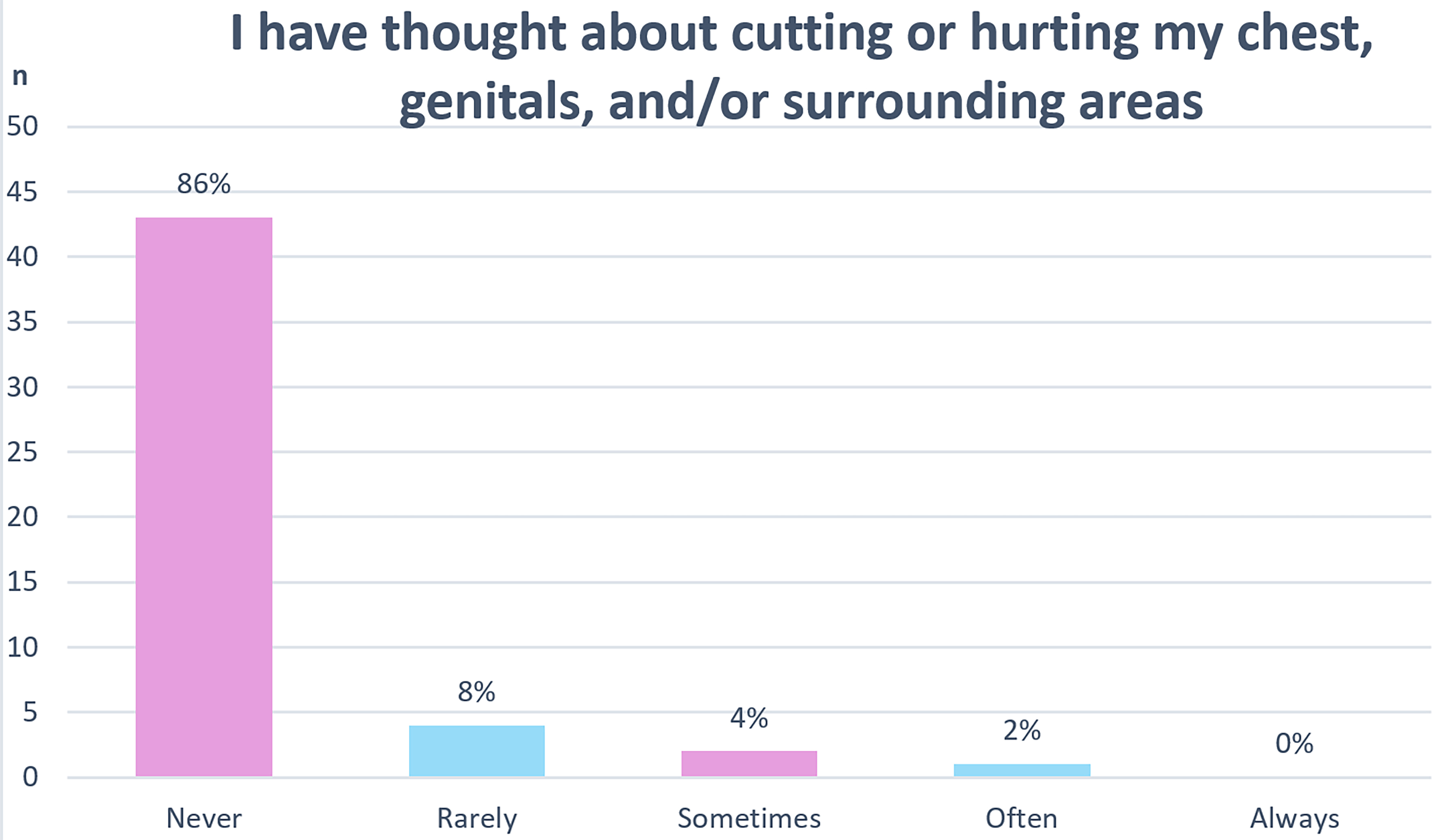

Thoughts about cutting or hurting their chest, genitals, or surrounding areas

Question 8 of the GCLS presents the item “I have thought about cutting or hurting my chest, genitals, and/or surrounding areas.” As shown in Figure 6, the majority of participants had never thought about cutting or hurting their chest, genitals, or surrounding areas. A small proportion of the participants reported rarely having these thoughts, whereas even fewer reported sometimes or often having such thoughts. The data were highly skewed toward “Never,” indicating that such thoughts were not common among the respondents in this sample.

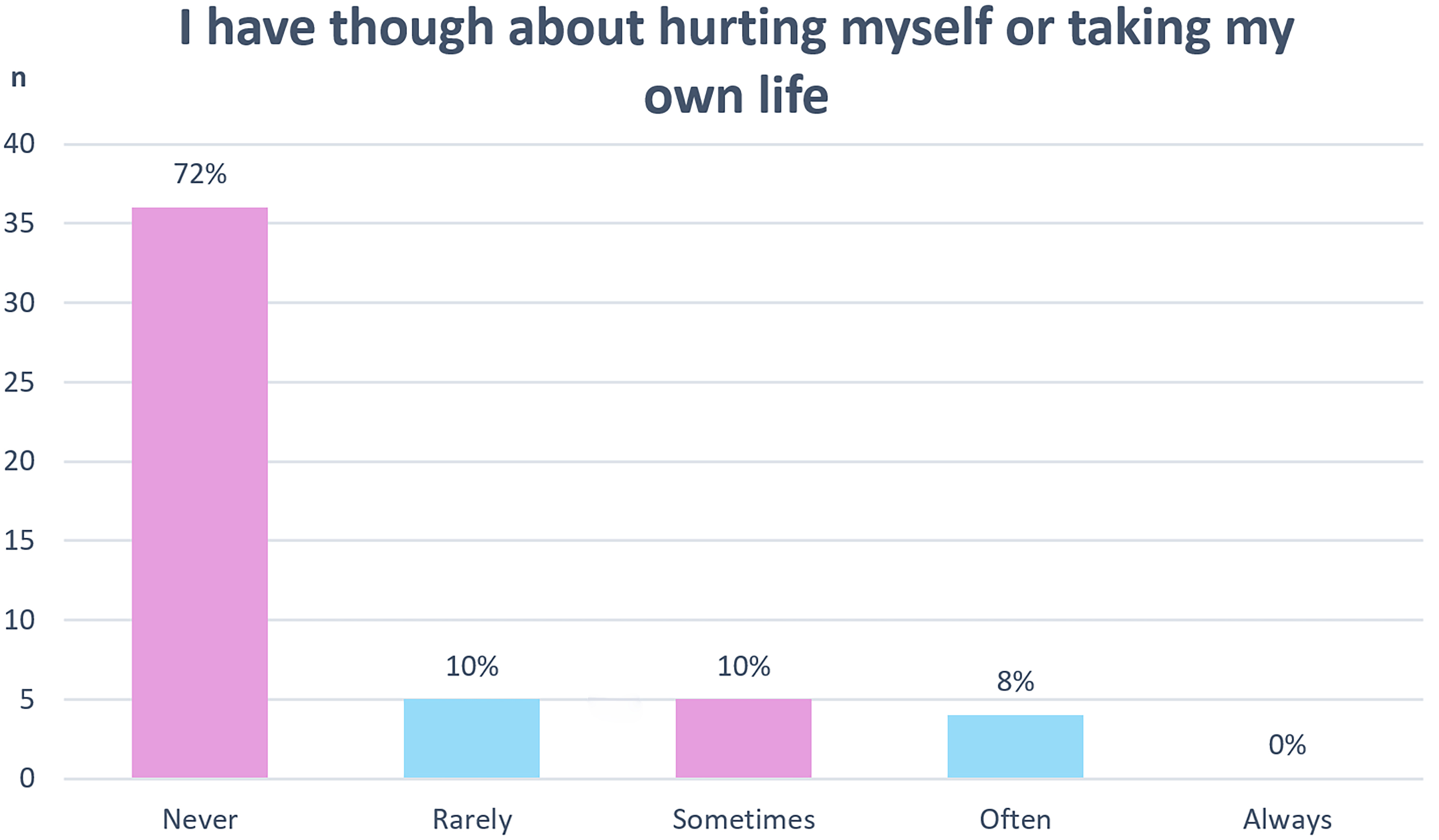

Suicidal ideation

Further insights from the GCLS revealed that a significant majority of respondents never considered self-harm or suicide; although some reported some thoughts of self-harm, none reported constant thoughts of self-harm. This distribution is depicted in Figure 7, pointing to a crucial minority struggling with severe mental health issues, which emphasizes the need for continued mental health support.

DISCUSSION

Assessing thoughts of self-harm or suicidal ideation in transgender women after GAS is crucial, given the high prevalence of these issues in the GD population. The psychological distress resulting from incongruence between an individual’s gender identity and gender assigned at birth can severely impact QoL and can lead to severe mental health issues, including ideation and attempt of self-harm or suicide[32-36].

This retrospective study aimed to enhance the understanding of life satisfaction, thoughts of self-harm or suicidal ideation among transgender women after genital GAS.

While we found that most participants (72%) had never experienced thoughts of self-harm or suicidal ideation, 28% of respondents had considered self-harm or suicide to some degree after GAS, indicating a substantial mental health challenge for this group. This aligns with other research on transgender individuals in Sweden, which showed that 36% had experienced suicidal thoughts or attempts in the past year[11].

Despite the presence of thoughts of self-harm or suicidal ideation, respondents reported overall satisfaction with life and mental health. Thus, surgical treatment may have had a positive impact on life satisfaction and gender congruence.

No patient in our case series, at the time the questionnaires were completed, had attempted self-harm or suicide. Our protocol for preventing self-harm and suicide begins even before surgery. In fact, a psychological assessment to determine readiness for surgery is required a few weeks before the procedure. Postoperatively, patients in Sweden are followed up at gender clinics for as long as necessary, with support from social workers and mental health professionals. Additionally, patients continue to be monitored by gender surgeons (as long as needed), endocrinologists (for lifelong follow-up), and general practitioners. This integrated approach ensures that patients receive comprehensive care, with timely referrals and access to mental health professionals when needed. This strategy was already in place before the study was conducted, and this study served to confirm the effectiveness of the existing routine.

These findings highlight the contrast between the transgender population and the general Swedish population, with only 3% of the latter reporting having considered taking their own lives at some point during the previous year[12]. This discrepancy underscores the severe mental health challenges that transgender individuals face. Higher rates of thoughts of self-harm or suicidal ideation may be attributed to various psychological and social factors, including stigma and discrimination[40].

The World Medical Association’s Declaration of Geneva stresses that physicians are ethically obliged to prioritize the health and well-being of their patients, without discrimination on any grounds[41]. This ethical obligation highlights the responsibility to treat all patients, ensuring that those with mental health conditions are not denied the care they need. Comprehensive medical care must be accessible to every individual, regardless of their mental health status, suicidal ideation, or self-harming.

Our study also explored the overall psychological health of the participants. As shown in Figure 1, most respondents expressed varying degrees of satisfaction with their mental health. GAS, such as vaginoplasty, has been linked to improvements in mental health[9]. Interestingly, despite these positive outcomes, 72% of the participants self-reported some form of mental illness [Table 4]. This suggests that many participants experienced positive psychological outcomes after surgery, even though they reported ongoing mental health issues. This may indicate that mental health diagnoses were made prior to surgery, and that these issues persisted even after physical transition. Thus, while the GAS may improve aspects of mental well-being, it does not entirely resolve pre-existing mental health conditions. Additionally, participants may perceive their current state as being more meaningful and joyful despite their mental health diagnoses, highlighting the complex interplay between physical transitions and mental health. However, these remain speculations, as we did not conduct a preoperative study to compare the mental health status before and after surgery. Future research should aim to provide a more holistic understanding of psychological outcomes following gender-affirming surgeries that address both immediate and long-term psychological needs.

Relationship between life satisfaction, self-harm, mental illness, and surgical complications

This manuscript is the first in a trilogy, specifically focusing on life satisfaction and self-harm. The second manuscript will address mental illness and QoL (also presenting Body-Image scale - BI-1), while the third will examine surgical complications and techniques. An integrated discussion will be provided in the manuscript on complications.

Regarding revision surgeries, most consisted of minor procedures, such as scar revisions, clitoral hood reconstruction, labia reduction, or vaginal dilation. Therefore, the reported 30% rate of revision surgeries, when considering the indications for surgery, does not correlate with self-harm or suicidal ideation. Instead, this revision rate should be compared to other centers where procedures such as episiotomy and clitoral hood reconstruction are performed in nearly 100% of cases. Although the manuscript dedicated to complications is still in progress, preliminary data suggest that the incidence of major complications in our cohort is exceptionally low, with rectovaginal fistula occurring in only 1.5% of cases.

Two patients who experienced rectovaginal fistula completed the current questionnaire. Both underwent successful reoperation and received bowel vaginoplasty within 18 months of their initial surgery. Despite their complications, both patients reported positive life satisfaction. Specifically, both responded that “life as a whole is quite satisfying” (Li-Sat-11, Question 1) and that they “rarely have not enjoyed life” (GCLS, Question 10). Furthermore, one patient reported never feeling life was meaningless, never having thoughts of cutting or harming their chest, genitals, or surrounding areas, and never having thoughts of self-harm or suicide. The second patient reported “rarely” feeling life was meaningless, “rarely” having thoughts of self-harm, and “sometimes” having thoughts of hurting themselves or taking their own life (GCLS, Questions 9, 8, and 7, respectively).

However, with only two patients experiencing such a major complication, the sample size is too small to draw statistically significant conclusions regarding the relationship between surgical complications and the risk of self-harm or suicidal ideation.

Strengths and weaknesses

A non-response analysis would have been beneficial because many patients did not respond to the survey. Understanding the characteristics of non-respondents could help to determine whether their absence introduced biases.

The lack of baseline data on patients’ QoL and mental health before surgery is a major limitation hindering the assessment of the impact of GAS on self-harm and suicidal thoughts.

Additionally, not accounting for patient-specific diagnoses (such as mental illnesses) limits our understanding of the distinct risks associated with suicidal behavior. Identifying the individual psychological profiles and diagnoses of the participants could yield deeper insights into the factors that contributed to thoughts of self-harm or suicidal ideation postoperatively.

Finally, for the next studies, we also recommend using the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) and Female Genital Self-Image Score (FGSIS).

In conclusion, our findings highlighted the critical issues of thoughts of self-harm or suicidal ideation that affected almost one-third of transgender women who have undergone GAS to some degree. Although the levels reported in our study were lower than those reported in other studies, the prevalence remains concerning and requires further attention. However, the study also showed that most participants reported enjoying their lives, feeling overall satisfaction, and finding meaning and purpose in life post-GAS. These findings underscore the need for both access to GAS and continued psychological support for this group. Improving QoL is the primary goal in the care of transgender individuals undergoing these procedures.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study and performed data analysis and interpretation: Selvaggi G, Larshans C, Georgas K, Rahimzadeh K, Olsson EM

Performed data acquisition, as well as providing administrative, technical, and material support: Selvaggi G, Larshans C, Georgas K, Rahimzadeh K, Olsson EM

Availability of data and materials

All the data and materials used in our study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

Selvaggi G is an Editorial Board member of Plastic and Aesthetic Research. Selvaggi G was not involved in any steps of editorial processing, notably including reviewer selection, manuscript handling, and decision making. The other authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority, application number 2020-03062. To protect patient anonymity, individuals were assigned codes prior to the questionnaire distribution. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants to ensure adherence to the ethical standards for research involving human subjects.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Linander I, Lauri M, Alm E, Goicolea I. Two steps forward, one step back: a policy analysis of the swedish guidelines for trans-specific healthcare. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2021;18:309-20.

2. Socialstyrelsen. God vård av vuxna med könsdysfori - Nationellt kunskapsstöd. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/kunskapsstod/2015-4-7.pdf. [Last accessed on 14 Mar 2025].

3. Socialstyrelsen. Till dig som möter personer med könsdysfori i ditt arbete. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2020-1-6580.pdf. [Last accessed on 14 Mar 2025].

4. Socialstyrelsen. Beslut om nationell högspecialiserad vård - viss vård vid könsdysfori. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/dokument-webb/ovrigt/nationell-hogspecialiserad-vard-konsdysfori-beslut.pdf. [Last accessed on 14 Mar 2025].

5. Sveriges riksdag. Hälso- och sjukvårdslag (SFS 2017:30). Available from: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/halso-och-sjukvardslag-201730_sfs-2017-30/. [Last accessed on 14 Mar 2025].

6. Socialstyrelsen. Ansökan om tillstånd att bedriva nationell högspecialiserad våred; viss vård vid könsdysfori. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/dokument-webb/ovrigt/nationell-hogspecialiserad-vard-namndbeslut-konsdysfori.pdf. [Last accessed on 14 Mar 2025].

7. Georgas K, Beckman U, Bryman I, et al. Gender affirmation surgery for gender dysphoria - effects and risks. Available from: https://mellanarkiv-offentlig.vgregion.se/alfresco/s/archive/stream/public/v1/source/available/sofia/su4372-1728378332-373/native/2018_102%20Rapport%20Könsdysfori.pdf. [Last accessed on 14 Mar 2025].

8. Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. Int J Transgend Health. 2022;23:S1-259.

9. Selvaggi G, Ceulemans P, De Cuypere G, et al. Gender identity disorder: general overview and surgical treatment for vaginoplasty in male-to-female transsexuals. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:135e-45e.

10. Selvaggi G, Dhejne C, Landen M, Elander A. The 2011 WPATH standards of care and penile reconstruction in female-to-male transsexual individuals. Adv Urol. 2012;2012:581712.

11. Folkhälsomyndigheten. Hälsan och hälsans bestämningsfaktorer för transpersoner - En rapport om hälsoläget bland transpersoner i Sverige. Available from: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/contentassets/c5ebbb0ce9aa4068aec8a5eb5e02bafc/halsan-halsans-bestamningsfaktorer-transpersoner.pdf. [Last accessed on 14 Mar 2025].

12. Folkhälsomyndigheten. Psykisk hälsa och suicid i Sverige - Statistik om nuläge och utveckling fram till 2022. Available from: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/publikationer-och-material/publikationsarkiv/p/psykisk-halsa-och-suicid-i-sverige-2022/?pub=126974. [Last accessed on 14 Mar 2025].

13. Rotondi NK, Bauer GR, Scanlon K, Kaay M, Travers R, Travers A. Prevalence of and risk and protective factors for depression in female-to-male transgender ontarians: trans PULSE project. Can J Community Ment Health. 2011;30:135-55.

14. Colizzi M, Costa R, Todarello O. Transsexual patients’ psychiatric comorbidity and positive effect of cross-sex hormonal treatment on mental health: results from a longitudinal study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;39:65-73.

15. Bauer GR, Scheim AI, Pyne J, Travers R, Hammond R. Intervenable factors associated with suicide risk in transgender persons: a respondent driven sampling study in Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:525.

16. James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The report of the 2015 US transgender survey. Available from: https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf. [Last accessed on 14 Mar 2025].

17. Klinitzke G, Steinig J, Blüher M, Kersting A, Wagner B. Obesity and suicide risk in adults--a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2013;145:277-84.

18. Bai W, Liu ZH, Jiang YY, et al. Worldwide prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide plan among people with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis and systematic review of epidemiological surveys. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:552.

19. Chen J, Ping Z, Hu D, Wang J, Liu Y. Risk factors associated with suicidal ideation among cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1287290.

20. La Vega D, Giner L, Courtet P. Suicidality in subjects with anxiety or obsessive-compulsive and related disorders: recent advances. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20:26.

21. Lerman SF, Sylvester S, Hultman CS, Caffrey JA. Suicidality after burn injuries: a systematic review. J Burn Care Res. 2021;42:357-64.

22. Fishbain DA, Lewis JE, Gao J. The pain suicidality association: a narrative review. Pain Med. 2014;15:1835-49.

23. Ayano G, Tsegay L, Abraha M, Yohannes K. Suicidal ideation and attempt among homeless people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatr Q. 2019;90:829-42.

24. Adams N, Hitomi M, Moody C. Varied reports of adult transgender suicidality: synthesizing and describing the peer-reviewed and gray literature. Transgend Health. 2017;2:60-75.

25. Virupaksha HG, Muralidhar D, Ramakrishna J. Suicide and suicidal behavior among transgender persons. Indian J Psychol Med. 2016;38:505-9.

26. Ryan EP, Oquendo MA. Suicide risk assessment and prevention: challenges and opportunities. Focus. 2020;18:88-99.

27. Gregory B, Peters L. Changes in the self during cognitive behavioural therapy for social anxiety disorder: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;52:1-18.

28. Reisner SL, Poteat T, Keatley J, et al. Global health burden and needs of transgender populations: a review. Lancet. 2016;388:412-36.

29. McCann E, Brown M. Vulnerability and psychosocial risk factors regarding people who identify as transgender. a systematic review of the research evidence. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2018;39:3-15.

30. Strang JF, Janssen A, Tishelman A, et al. Revisiting the link: evidence of the rates of autism in studies of gender diverse individuals. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;57:885-7.

31. Heylens G, Aspeslagh L, Dierickx J, et al. The co-occurrence of gender dysphoria and autism spectrum disorder in adults: an analysis of cross-sectional and clinical chart data. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48:2217-23.

32. Oles N, Darrach H, Landford W, et al. Gender affirming surgery: a comprehensive, systematic review of all peer-reviewed literature and methods of assessing patient-centered outcomes (Part 2: genital reconstruction). Ann Surg. 2022;275:e67-74.

33. Javier C, Crimston CR, Barlow FK. Surgical satisfaction and quality of life outcomes reported by transgender men and women at least one year post gender-affirming surgery: a systematic literature review. Int J Transgend Health. 2022;23:255-73.

34. Kuhn A, Bodmer C, Stadlmayr W, Kuhn P, Mueller MD, Birkhäuser M. Quality of life 15 years after sex reassignment surgery for transsexualism. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1685-9.e3.

35. van de Grift TC, Elaut E, Cerwenka SC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Kreukels BPC. Surgical satisfaction, quality of life, and their association after gender-affirming surgery: a follow-up study. J Sex Marital Ther. 2018;44:138-48.

36. Monteiro Petry Jardim LM, Cerentini TM, Lobato MIR, et al. Sexual function and quality of life in brazilian transgender women following gender-affirming surgery: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:15773.

37. Fugl-meyer AR, Bränholm I, Fugl-meyer KS. Happiness and domain-specific life satisfaction in adult northern Swedes. Clin Rehabil. 1991;5:25-33.

38. Melin R, Fugl-Meyer KS, Fugl-Meyer AR. Life satisfaction in 18- to 64-year-old Swedes: in relation to education, employment situation, health and physical activity. J Rehabil Med. 2003;35:84-90.

39. Jones BA, Bouman WP, Haycraft E, Arcelus J. The gender congruence and life satisfaction scale (GCLS): development and validation of a scale to measure outcomes from transgender health services. Int J Transgend. 2019;20:63-80.

40. Valentine SE, Shipherd JC. A systematic review of social stress and mental health among transgender and gender non-conforming people in the United States. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;66:24-38.

41. World Medical Association. WMA Declaration of Geneva. Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-geneva/. [Last accessed on 14 Mar 2025].

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].