Crystallization regulation of Fe0@Fe3O4 using a g-C3N4/diatomite composite for enhancing photocatalytic peroxymonosulfate activation

Abstract

Photocatalysis and persulfate synergistic catalysis have recently become promising technologies for degrading refractory organic contaminants in effluents. In this work, Fe0@Fe3O4 is successfully immobilized on a

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Water body pollution by xenobiotic chemicals has become a global issue that affects the survival of all living creatures[1,2]. In order to treat xenobiotic chemicals, various strategies, such as adsorption, precipitation, filtration and biological treatment, have been employed. In particular, advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) have become popular for removing contaminants from effluents in recent decades due to their excellent capability for high mineralizing rates[3-5]. Furthermore, photocatalysis has also emerged as a promising solution for the purification of effluents by solar energy harvesting. Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) is endowed with outstanding photocatalytic ability due to its narrow band gap (2.7 eV), non-toxicity and high stability. However, the low surface area and sluggish photogenerated carrier transfer of g-C3N4 hinder its wide application[6-8].

Therefore, the modification of g-C3N4 via doping or coupling with other materials (like Ag3PO4, BiOCl, CoTiO3 and natural minerals) for improved surface area and better effluent cleaning performance has been reported[8]. Our group has already carried out work in adopting diatomite (SiO2·nH2O) as the carrier of

In addition, sulfate radical-advanced oxidation processes (SR-AOPs) have become important for the removal of recalcitrant pollutants, owing to their wider pH range (2-8) compared with Fenton systems

To further overcome the limitations of g-C3N4/diatomite (GD) and iron-based catalysts, this study combines photocatalysis and SR-AOPs to synthesize Fe0@Fe3O4/N-deficient g-C3N4/diatomite composites (FNGD). Notably, we systematically characterize the prepared FNGD materials, evaluate the catalytic performance of FNGD samples for PMS activation under visible-light irradiation and explore the involvement of active species including reactive oxygen species (ROS) together with photoexcited electron-hole pairs for the removal mechanism of bisphenol A (BPA). We also examine the effects of the operating parameters (BPA and PMS concentrations, pH value and catalyst dosage) and background species (inorganic anions) on the degradation performance of BPA in the 0.6-FNGD/PMS/Vis system.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Dicyandiamide (C2H4N4), ammonium persulfate [(NH4)2S2O8], ferrous acetate (C4H6FeO4·4H2O),

Sample preparation

g-C3N4 and GD were prepared according to our previous report[20]. N-deficient g-C3N4/diatomite (NGD) was synthesized through a thermal oxidation method. Typically, 5.0 g of diatomite (1.0 g) and dicyandiamide (4.0 g) were mixed uniformly with 1.5 g of (NH4)2S2O8 in an agate mortar. The product was then heated at 550 °C for 4 h under an air atmosphere with a heating rate of 2.3 °C/min.

The FNGD composites were synthesized as follows. Firstly, 0.5 g of NGD and x mmol of C4H6FeO4·4H2O

Characterization

X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) was applied to investigate the phase structure of the prepared materials. Fourier transformed infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was performed to analyze the interaction of prepared materials. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) were employed to observe the morphologies and elemental distribution of the prepared FNGD materials, respectively. The pore structure parameters of the as-prepared samples were obtained using multipoint N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms with Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) and Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) methods. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was applied to identify the surface chemical bonds of the 0.6-FNGD composite. Ultraviolet-visible diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (UV-vis DRS) was applied to observe the optical adsorption and band structure of the FNGD and contrastive samples. The electrochemical properties, including the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and transient photocurrent response, of selected samples were tested. Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) was used to detect the Fe leaching concentration and Fe ion content of 0.6-FNGD. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) was applied under different reaction systems.

Evaluation of catalytic activity

In the degradation process, 15 mg of x-FNGD were dispersed into 30 mL of BPA solution (15 mg/L). Afterward, the suspension was dispersed uniformly under ultrasound for 1 min and then stirred in dark conditions for 15 min to achieve the adsorption-desorption equilibrium. Subsequently, a PMS solution

The concentration of BPA was evaluated using high-performance liquid chromatography (LC-2030C Shimadzu, Japan) with a C18 reverse-phase column. The mobile phase consisted of ultrapure water (40%) and acetonitrile (60%) with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The detection wavelength was 223 nm and the injection volume was 10 μL.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Characterization of catalysts

The phase structures of the Fe0@Fe3O4, NGD and FNGD composites are exhibited in Figure 1A. The XRD pattern of pure Fe0@Fe3O4 shows the characteristic peaks at 2θ = 35.42° and 44.68°, which correspond to the lattice planes of magnetite (JCPDS No. 19-0629)[22] and iron (JCPDS No. 87-0721)[23], respectively, suggesting the successful synthesis of Fe0@Fe3O4. However, the prepared FNGD composites did not exhibit any characteristic peaks of magnetite and iron. The possible reason for this phenomenon is explained in the XPS part. Furthermore, the peaks centered at 2θ = 21.8° and 26.70° in the XRD patterns of the NGD and FNGD composites are attributed to amorphous SiO2[24] and quartz impurities[25], respectively. Furthermore, the XRD patterns of NGD, 0.2-FNGD and 0.4-FNGD all show characteristic peaks at 12.85° and 27.55°, corresponding to the lattice planes of g-C3N4 (JCPDS No. 87-1526)[10], suggesting the good assembly of

Figure 1. (A) XRD patterns of Fe0@Fe3O4, NGD and the prepared FNGD composites. (B) FTIR spectra of 0.6-FNGD composite and contrastive samples. (C) Partial enlargements of FTIR spectra.

Furthermore, the chemical structures of g-C3N4, NGD, 0.6-FNGD and Fe0@Fe3O4 were analyzed by FTIR, as shown in Figure 1B. For the prepared g-C3N4, the two broad adsorption peaks at 3450 and 3350-2950 cm-1 were caused by the O-H (adsorbed H2O) and N-H stretching vibrations. The N-H bond results from the incomplete polycondensation of the edges of the s-triazine ring system. The adsorption peaks at 1200-1650 and 809 cm-1 originate from the typical stretching vibration of C=N and C-N heterocycles[26]. For the NGD material, two fresh adsorption peaks centered at 1100 and 468 cm-1 appeared, belonging to the Si-O stretching vibration of diatomite[27]. The adsorption peak at ~3658-3345 cm-1 is attributed to the stretching vibration of the Si-OH groups[28]. The above results indicate that the chemical structure of diatomite and

The morphologies of the diatomite, Fe0@Fe3O4 and 0.6-FNGD are shown in Figure 2. The diatomite

Figure 2. SEM images of (A) diatomite, (B) Fe0@Fe3O4, (C and D) 0.6-FNGD and (E) SEM-EDS elemental mapping of Si, C, N and Fe for 0.6-FNGD composite.

For the further investigation of the pore structural parameters of the diatomite, g-C3N4, Fe0@Fe3O4, NGD and 0.6-FNGD composites, the obtained N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms and pore diameter distribution curves are exhibited in Figure 3. The results of the BET surface area, pore volume and average pore diameter are also calculated and listed in Table 1. As illustrated in Figure 3A, diatomite exhibited a typical II adsorption isotherm representative of the presence of a nonporous or macroporous structure. In contrast, g-C3N4, Fe0@Fe3O4, NGD and 0.6-FNGD all presented typical IV adsorption isotherms with an H3 hysteresis loop, suggesting the presence of a mesoporous structure[10,30]. In addition, the pore size distribution was concentrated with the tendency of small pore sizes for 0.6-FNGD, as exhibited in Figure 3B, which might be due to the uniform loading of Fe0@Fe3O4 substances onto the NGD.

Figure 3. (A) N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms and (B) BJH pore size distribution plots of diatomite, g-C3N4, Fe0@Fe3O4, NGD and 0.6-FNGD.

BET surface area, pore volume and average pore size of diatomite, g-C3N4, Fe0@Fe3O4, NGD and 0.6-FNGD composites

| Sample | SBET (m2/g) | Total pore volume (cm3/g) | Average pore diameter (nm) |

| Diatomite | 15.45 | 0.046 | 11.8 |

| g-C3N4 | 18.71 | 0.102 | 21.7 |

| Fe0@Fe3O4 | 28.71 | 0.106 | 14.8 |

| NGD | 25.29 | 0.132 | 20.8 |

| 0.6-FNGD | 38.61 | 0.177 | 18.3 |

As listed in Table 1, compared with diatomite, g-C3N4, Fe0@Fe3O4 and NGD, 0.6-FNGD has a larger specific surface area (38.61 m2/g) and higher pore volume (0.177 cm3/g). This suggests that the ternary FNGD catalyst might have a good adsorption performance and more contact opportunities for active sites with PMS and BPA, thus improving the catalytic degradation performance.

The chemical composition and binding bonds of 0.6-FNGD were further investigated by XPS, as displayed in Figure 4. The survey scan of 0.6-FNGD exhibited the characteristic peaks of Si 2p, C 1s, N 1s, O 1s and Fe 2p. In the Si 2p spectra of 0.6-FNGD, the peak at 104.2 eV can be ascribed to the Si-O-C bond, owing to the bonding between the surface oxygen atom of diatomite and the carbon atom of g-C3N4. As exhibited in Figure 4C, the O 1s curve of 0.6-FNGD showed three peaks at 533.1, 532.3 and 531.8 eV, which were attributed to the Si-O bond of SiO2, the surface OH of diatomite and N-C-O bonds, respectively[31,32]. This result indicates the successful bonding between g-C3N4 and the microsized diatomite particles.

Figure 4. (A) Full XPS spectra and survey spectra of (B) Si 2p, (C) O 1s, (D) C 1s, (E) N 1s and (F) Fe 2p for 0.6-FNGD material.

In addition, three peaks at 288.1, 286.0 and 284.78 eV in the C 1s spectrum were caused by the C=N, C-NHx and C-C bonds of g-C3N4 and NGD, respectively[33]. However, the binding energy of hybridized N (C=N-C) shifted to 398.47 eV and the Fe-N located at 399.9 eV proves that the Fe species were stabilized in the electron-rich g-C3N4[34], which was in good agreement with the result of Fe ions leaching in the 0.6-FNGD material. More importantly, the chemical bonding between Fe and N [Figure 4E], which are the active sites[23] that might affect the crystal phase of magnetite and iron metal in the catalytic reaction, with implementation of crystallization regulation of Fe0@Fe3O4. As shown in Figure 4F, the two peaks at 710.5 and 724.0 eV were ascribed to Fe3+ and Fe2+, respectively. Nevertheless, the peak of Fe0 at ~706 eV is not observed, which might be attributed to the limited XPS detection depth (< 10 nm) and the fact that the catalyst can be oxidated by air[35].

To assess the effect of the amount of Fe0@Fe3O4 on the optical adsorption and band structure of FNGD, the UV-vis diffuse reflectance spectra of 0.6-FNGD, 0.4-FNGD, 0.2-FNGD and NGD were investigated. As shown in Figure 5A, FNGD not only exhibited inherent optical adsorption of g-C3N4 with an adsorption edge at 460 nm that originates from the π-conjugated C-N heterocycles, but also showed a gradually stronger uplift of the absorption tail in the range of 450-800 nm. Furthermore, the direct bandgap (Eg) results of FNGD [Figure 5B] indicate that the value of Eg decreases gradually somewhat with the introduction of Fe0@Fe3O4, suggesting its promotional effect on the visible-light adsorption ability of NGD.

As depicted in Figure 6A, a much smaller arc radius of the Nyquist circle was observed in the presence of 0.6-FNGD than that of GD, reflecting a lower internal electron transfer resistance. This proves that 0.6-FNGD features greatly improved charge separation and transfer efficiency of generated electron-hole pairs[36]. In addition, some selected materials, including 0.6-FNGD, NGD and NG, showed obvious photocurrent responses during the repeated light (on/off) cycles, as shown in Figure 6B[37]. The photocurrent response order was 0.6-FNGD (1.72 × 10-6) > NGD (1.57 × 10-6) > NG (1.43 × 10-6). This result suggests that the combination of NG with diatomite and the introduction of Fe0@Fe3O4 effectively improved the separation and transfer efficiency of electron-hole pairs[38].

Catalytic efficiency of catalysts

The catalytic efficiency of the NGD, Fe0@Fe3O4 and FNGD composites was evaluated for BPA degradation by activating PMS under visible-light irradiation [Figure 7A]. The removal percentage of BPA was only 11% for NGD and 17% for Fe0@Fe3O4 after 15 min, indicating their poor catalytic activity. In contrast, the FNGD composites presented a high removal percentage (> 87%) of BPA within 15 min, showing that the combination of Fe0@Fe3O4 and NGD contributes to the successful construction of efficient catalytic materials. The removal percentage of BPA for 0.6-FNGD and 1.2-FNGD was similar (> 95% within 15 min). Hereupon, the prepared 0.6-FNGD (Fe ion content = 5.56 wt.% by ICP-OES) was chosen as the optimum material for all the following experiments. However, the degradation velocity of BPA decreased when further increasing the amount of C4H6FeO4·4H2O from 1.2 to 1.8 mmol. The reason is that the corresponding coverage of Fe0@Fe3O4 on the NGD might be incomplete, thus weakening the interactions between Fe0@Fe3O4 and NGD[39].

Figure 7. Removal of (A) BPA and (B) linear transform ln(C0/C) of kinetic curves of NGD, Fe0@Fe3O4 and the prepared FNGD composites. (C) Removal of BPA in different systems. Effect of (D) BPA concentration, (E) PMS concentration, (F) 0.6-FNGD dosage, (G) initial pH and (H) inorganic anion effect on BPA degradation in

The pseudo-first-order kinetic constant (k) in linear transforms Ln(C0/Ct) = kt of BPA degradation on NGD, Fe0@Fe3O4 and some selected FNGD composites are displayed in Figure 7B. Among these, 0.6-FNGD exhibited a high reaction activity (k = 322 × 10-5 s-1) that was 59 times higher than NGD (k = 5.43 × 10-5 s-1) and 27 times higher than Fe0@Fe3O4 (k = 11.89 × 10-5 s-1), illustrating the superior degradation rate of BPA in the FNGD/PMS/Vis system and proving the superiority of the FNGD composites. Furthermore, as exhibited in Figure 7C, only 2% and 1% of BPA were removed in the PMS alone and Vis alone systems, respectively, suggesting that PMS or visible light cannot degrade BPA directly. Notably, the removal percentage of BPA reached up to 98% in the 0.6-FNGD/PMS/Vis system, suggesting the synergistic effect between PMS and visible-light irradiation[40].

To determine the practical application of the 0.6-FNGD/PMS/Vis system, the effects of BPA and PMS concentrations and catalyst dosages on BPA degradation were explored [Figure 7D-F]. As shown in Figure 7D, BPA can be removed completely within 5 and 10 min at the initial concentrations of 5 and

As exhibited in Figure 7E, the degradation of BPA was rapidly promoted with the increase of PMS dosage from 28 to 72 mg/L. In contrast, the increasing velocity decreased with excessive PMS dosage, especially from 72 to 95 mg/L, which might be attributed to the excessive PMS promoting competitive reactions that consume oxidants and the limited generation rate of active species without extra 0.6-FNGD[41]. As exhibited in Figure 7F, the removal percentage of BPA was rapidly promoted when the 0.6-FNGD dosage increased from 0.25 to 0.5 g/L, suggesting that the extra 0.6-FNGD dosage could provide more available active sites when the amount of catalyst is relatively low.

In addition, the effects of pH (3-11) and inorganic anions (Cl-, HCO3-, H2PO4-) on BPA degradation were also explored [Figure 7G and H]. As displayed in Figure 7G, the removal percentages of BPA were maintained well in the pH range from 3 to 9 (> 73% within 15 min) and decreased rapidly when the pH value was 11. The sudden drop at pH = 11 was due to the generation of SO52-, which prevented the generation of SO4•- and •OH in the 0.6-FNGD/PMS/Vis system[42]. Thus, the prepared FNGD material can be applied well in weakly acidic or alkaline environments. As shown in Figure 7H, no obvious effect on BPA degradation could be noticed after the addition of Cl-. As for HCO3- and H2PO4-, the inhibition effect was observed, mainly owing to the strong quenching of HCO3- for SO4•- and •OH[43], as well as the complexation of H2PO4- with iron[44]. Furthermore, the addition of HCO3- and H2PO4- can also increase the pH value and induce a decrease in the removal percentage of BPA[45].

In addition, the Fe leaching concentration of 0.6-FNGD in the BPA degradation process was studied by ICP-OES analysis. As displayed in Figure 7I, the Fe leaching concentration of 0.6-FNGD after three cycles is lower than 0.15 mg/L, which is below the Chinese Surface Water Environmental Quality Standard (Fe is 0.30 mg/L stipulated in GB 3838-2002). Overall, the above results indicate that the 0.6-FNGD/PMS/Vis system is efficient and environmentally friendly for BPA removal.

Reaction mechanism

To identify the involved reactive species in the FNGD/PMS/Vis system, a quenching experiment was conducted using TBA (20 mM), MeOH (20 mM), BQ (10 mM), L-histidine (50 mM), FFA (50 mM) and EDTA-2Na (10 mM) to capture •OH, SO4•-, •O2-, 1O2 and hvb+, respectively. As displayed in Figure 8A, the removal percentage of BPA decreased slightly when adding TBA and MeOH, suggesting that •OH and SO4•- acted in a secondary role in the FNGD/PMS/Vis system. Impressively, when BQ, L-histidine, FFA and EDTA-2Na were added, the removal percentage of BPA decreased to 44%, 13%, 11% and 9%, respectively, indicating that the •O2-, 1O2 and hvb+ play a major role in the degradation process with the significant order of hvb+ > 1O2 > •O2-. Overall, radical and non-radical pathways work together to oxidize pollutants in the FNGD/PMS/Vis system.

Figure 8. (A) Effects of different scavengers on BPA removal. EPR spectra of (B) 1O2, (C) •O2-, (D) •OH and SO4•- over 0.6-FNGD in different systems.

In-situ EPR was further applied to detect the generated reactive species in the PMS and PMS+Vis systems. As displayed in Figure 8B-D, the characteristic signals for 1O2 (totality 3), •O2- (totality 4), •OH (totality 4) and SO4•- (totality 6) were obtained in the FNGD/PMS and FNGD/PMS/Vis systems. Furthermore, the signal intensity of 1O2 in the FNGD/PMS/Vis system was stronger than that in the FNGD/PMS system, proving the synergetic effect of PMS under visible-light irradiation. Likewise, the signal enhancement was also observed in Figure 8C and D, which was consistent with the results of the above characterization and degradation experiments.

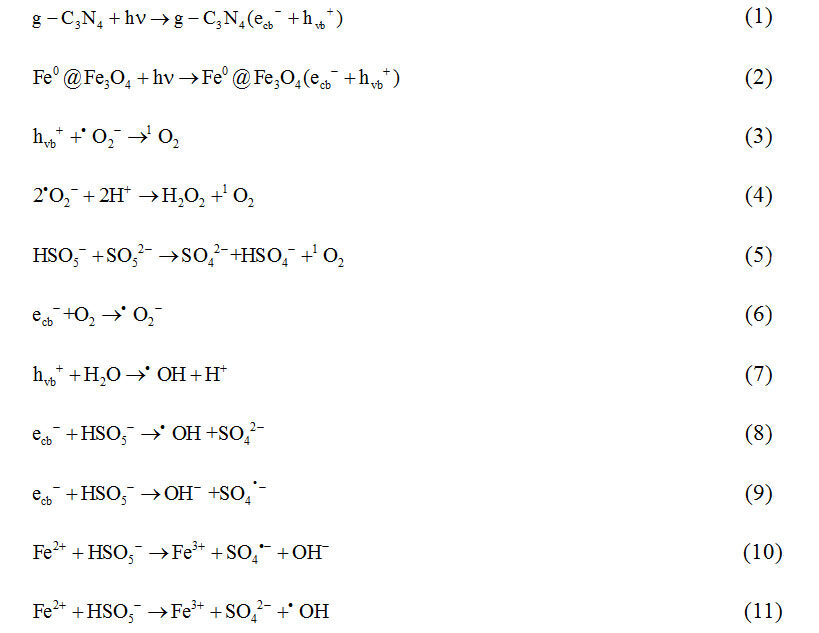

Based on the above results, the possible mechanism of BPA removal in the FNGD/PMS/Vis system is proposed and displayed below: (1) g-C3N4 and Fe0@Fe3O4 generate electron-hole pairs [Equations 1 and 2] under visible-light irradiation with improved optical adsorption ability, transfer efficiency and charge separation by heterojunction, thereby enhancing the photocatalytic performance[46]; (2) the •O2- reacts with hvb+ and H+ to generate 1O2 [Equations 3 and 4]; (3) the generated ecb- (from g-C3N4 and Fe0@Fe3O4) and Fe2+ (from Fe0 and Fe3O4) can also react with PMS to produce ROS [Equations 5-11][16]; (4) the prepared FNGD is beneficial to expose more active sites through increased BET and pore volume. Furthermore, the surface -OH of diatomite can facilitate the activation of PMS to generate SO4•- and •OH[45]. The possible generation methods of radicals and non-radicals following the significant order (hvb+ > 1O2 > •O2- > •OH and SO4•-) in the FNGD/PMS/Vis system are listed below:

CONCLUSION

Fe0@Fe3O4/N-deficient g-C3N4/diatomite composites were successfully synthesized. The prepared 0.6-FNGD material exhibited an excellent reaction rate constant (k = 322 × 10-5 s-1), which was up to ~59 and ~27 times higher than that of N-deficient g-C3N4/diatomite (k = 5.43 × 10-5 s-1) and bare Fe0@Fe3O4 (k =11.89 × 10-5 s-1) under the PMS/Vis system. The introduction of NGD affects the crystallization and morphology of

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributionsConceptualization, investigation, writing - original draft: Wang X

Methodology, investigation: Zhang X, Zhou H

Supervision, writing - review & editing: Li C

Conceptualization, writing - review & editing, funding acquisition, resources: Sun Z

Availability of data and materialsNot applicable.

Financial support and sponsorshipThe authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the Fok Ying Tung Education Foundation, China (171042), and the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (2202044 and 2214076).

Conflicts of interestNone.

Ethical approval and consent to participateNot applicable.

Copyright© The Author(s) 2022.

REFERENCES

1. Crini G, Lichtfouse E. Advantages and disadvantages of techniques used for wastewater treatment. Environ Chem Lett 2019;17:145-55.

2. Yaqoob AA, Parveen T, Umar K, Mohamad Ibrahim MN. Role of nanomaterials in the treatment of wastewater: a review. Water 2020;12:495.

3. Dharupaneedi SP, Nataraj SK, Nadagouda M, Reddy KR, Shukla SS, Aminabhavi TM. Membrane-based separation of potential emerging pollutants. Sep Purif Technol 2019;210:850-66.

4. Ganzenko O, Huguenot D, van Hullebusch ED, Esposito G, Oturan MA. Electrochemical advanced oxidation and biological processes for wastewater treatment: a review of the combined approaches. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2014;21:8493-524.

5. Oh W, Dong Z, Lim T. Generation of sulfate radical through heterogeneous catalysis for organic contaminants removal: Current development, challenges and prospects. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2016;194:169-201.

6. Chen X, Shi R, Chen Q, et al. Three-dimensional porous g-C3N4 for highly efficient photocatalytic overall water splitting. Nano Energy 2019;59:644-50.

7. Oliveros AN, Pimentel JAI, de Luna MDG, Garcia-segura S, Abarca RRM, Doong R. Visible-light photocatalytic diclofenac removal by tunable vanadium pentoxide/boron-doped graphitic carbon nitride composite. Chem Engin J 2021;403:126213.

8. Paragas LKB, Dien Dang V, Sahu RS, et al. Enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of acetaminophen over CeO2/I, K-codoped C3N4 heterojunction with tunable properties in simulated water matrix. Sep Purif Technol 2021;272:117567.

9. Zhang X, Li C, Chen T, et al. Enhanced visible-light-assisted peroxymonosulfate activation over MnFe2O4 modified g-C3N4/diatomite composite for bisphenol A degradation. Int J Min Sci Techn 2021;31:1169-79.

10. Yuan F, Sun Z, Li C, Tan Y, Zhang X, Zheng S. Multi-component design and in-situ synthesis of visible-light-driven SnO2/g-C3N4/diatomite composite for high-efficient photoreduction of Cr(VI) with the aid of citric acid. J Hazard Mater 2020;396:122694.

11. Jiang Z, Zhu H, Guo W, et al. Ag3VO4/g-C3N4/diatomite ternary compound reduces Cr(vi) ion in aqueous solution effectively under visible light. RSC Adv 2022;12:7671-9.

12. Xiao S, Cheng M, Zhong H, et al. Iron-mediated activation of persulfate and peroxymonosulfate in both homogeneous and heterogeneous ways: a review. Chem Engin J 2020;384:123265.

13. Cao J, Lai L, Lai B, Yao G, Chen X, Song L. Degradation of tetracycline by peroxymonosulfate activated with zero-valent iron: performance, intermediates, toxicity and mechanism. Chem Engin J 2019;364:45-56.

14. Fan J, Zhao Z, Ding Z, Liu J. Synthesis of different crystallographic FeOOH catalysts for peroxymonosulfate activation towards organic matter degradation. RSC Adv 2018;8:7269-79.

15. Long Y, Li S, Su Y, et al. Sulfur-containing iron nanocomposites confined in S/N co-doped carbon for catalytic peroxymonosulfate oxidation of organic pollutants: Low iron leaching, degradation mechanism and intermediates. Chem Engin J 2021;404:126499.

16. Wang S, Wang J. Synergistic effect of PMS activation by Fe0@Fe3O4 anchored on N, S, O co-doped carbon composite for degradation of sulfamethoxazole. Chem Engin J 2022;427:131960.

17. Yan Y, Zhang H, Wang W, Li W, Ren Y, Li X. Synthesis of Fe0/Fe3O4@porous carbon through a facile heat treatment of iron-containing candle soots for peroxymonosulfate activation and efficient degradation of sulfamethoxazole. J Hazard Mater 2021;411:124952.

18. Wan D, Li W, Wang G, Lu L, Wei X. Degradation of p-Nitrophenol using magnetic Fe0/Fe3O4/Coke composite as a heterogeneous Fenton-like catalyst. Sci Total Environ 2017;574:1326-34.

19. Yang R, Li C, Yuan F, Wu C, Sun Z, Ma R. Synergistic effect of diatomite and Bi self-doping Bi2MoO6 on visible light photodegradation of formaldehyde. Microporous Mesoporous Mater 2022;339:112003.

20. Sun Z, Li C, Yao G, Zheng S. In situ generated g-C3N4/TiO2 hybrid over diatomite supports for enhanced photodegradation of dye pollutants. Materials & Design 2016;94:403-9.

21. Serrà A, Philippe L, Perreault F, Garcia-Segura S. Photocatalytic treatment of natural waters. Reality or hype? Water Res 2021;188:116543.

22. Dheyab MA, Aziz AA, Jameel MS, Noqta OA, Khaniabadi PM, Mehrdel B. Simple rapid stabilization method through citric acid modification for magnetite nanoparticles. Sci Rep 2020;10:10793.

23. Neeli ST, Ramsurn H. Synthesis and formation mechanism of iron nanoparticles in graphitized carbon matrices using biochar from biomass model compounds as a support. Carbon 2018;134:480-90.

24. Zhang G, Sun Z, Duan Y, Ma R, Zheng S. Synthesis of nano-TiO2 /diatomite composite and its photocatalytic degradation of gaseous formaldehyde. Appl Surf Sci 2017;412:105-12.

25. Marinoni N, Broekmans MA. Microstructure of selected aggregate quartz by XRD, and a critical review of the crystallinity index. Cem Concr Res 2013;54:215-25.

26. Liu X, Wang P, Zhai H, et al. Synthesis of synergetic phosphorus and cyano groups (CN) modified g-C3N4 for enhanced photocatalytic H2 production and CO2 reduction under visible light irradiation. Appl Catalysis B: Envir 2018;232:521-30.

27. Khraisheh MA, Al-Ghouti MA, Allen SJ, Ahmad MN. Effect of OH and silanol groups in the removal of dyes from aqueous solution using diatomite. Water Res 2005;39:922-32.

28. Xu L, Gao X, Li Z, Gao C. Removal of fluoride by nature diatomite from high-fluorine water: an appropriate pretreatment for nanofiltration process. Desalination 2015;369:97-104.

29. Gerber SJ, Erasmus E. Electronic effects of metal hexacyanoferrates: an XPS and FTIR study. Mater Chem Phys 2018;203:73-81.

30. Jia Z, Li T, Zheng Z, et al. The BiOCl/diatomite composites for rapid photocatalytic degradation of ciprofloxacin: Efficiency, toxicity evaluation, mechanisms and pathways. Chemical Engineering Journal 2020;380:122422.

31. Antunes VG, Figueroa CA, Alvarez F. Chemisorption competition between H2O and H2 for sites on the Si Surface under Xe+ Ion bombardment: an XPS study. Langmuir 2022;38:2109-16.

32. He H, Luo Z, Yu C. Diatomite-anchored g-C3N4 nanosheets for selective removal of organic dyes. J Alloys Comp 2020;816:152652.

33. Shi G, Lv S, Cheng X, Wang X, Li S. Enhanced microwave absorption properties of modified Ni@C nanocapsules with accreted N doped C shell on surface. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron 2018;29:17483-92.

34. Gao J, Wang Y, Zhou S, Lin W, Kong Y. A facile one-step synthesis of Fe-doped g-C3N4 nanosheets and their improved visible-light photocatalytic performance. ChemCatChem 2017;9:1708-15.

35. Chen S, Deng J, Ye C, et al. Degradation of p-arsanilic acid by pre-magnetized Fe0/persulfate system: Kinetics, mechanism, degradation pathways and DBPs formation during subsequent chlorination. Chem Engin J 2021;410:128435.

36. Bi L, Gao X, Ma Z, Zhang L, Wang D, Xie T. Enhanced Separation Efficiency of PtNix/g-C3N4 for Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production. ChemCatChem 2017;9:3779-85.

37. Garcia-segura S, Tugaoen HO, Hristovski K, Westerhoff P. Photon flux influence on photoelectrochemical water treatment. Electr Commun 2018;87:63-5.

38. Li Y, Jin Z, Zhang L, Fan K. Controllable design of Zn-Ni-P on g-C3N4 for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen production. Chinese J Catal 2019;40:390-402.

39. Xu M, Li J, Yan Y, et al. Catalytic degradation of sulfamethoxazole through peroxymonosulfate activated with expanded graphite loaded CoFe2O4 particles. Chem Engin J 2019;369:403-13.

40. Shao H, Zhao X, Wang Y, et al. Synergetic activation of peroxymonosulfate by Co3O4 modified g-C3N4 for enhanced degradation of diclofenac sodium under visible light irradiation. Appl Catal B: Envir 2017;218:810-8.

41. Chen G, Zhang X, Gao Y, Zhu G, Cheng Q, Cheng X. Novel magnetic MnO2/MnFe2O4 nanocomposite as a heterogeneous catalyst for activation of peroxymonosulfate (PMS) toward oxidation of organic pollutants. Separ Purif Techn 2019;213:456-64.

42. Li C, Huang Y, Dong X, et al. Highly efficient activation of peroxymonosulfate by natural negatively-charged kaolinite with abundant hydroxyl groups for the degradation of atrazine. Appl Catal B: Envir 2019;247:10-23.

43. An L, Xiao P. Zero-valent iron/activated carbon microelectrolysis to activate peroxydisulfate for efficient degradation of chlortetracycline in aqueous solution. RSC Adv 2020;10:19401-9.

44. Rao Y, Han F, Chen Q, et al. Efficient degradation of diclofenac by LaFeO3-Catalyzed peroxymonosulfate oxidation---kinetics and toxicity assessment. Chemosphere 2019;218:299-307.

45. Zhang X, Duan J, Tan Y, Deng Y, Li C, Sun Z. Insight into peroxymonosulfate assisted photocatalysis over Fe2O3 modified TiO2/diatomite composite for highly efficient removal of ciprofloxacin. Separ Purif Techn 2022;293:121123.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, H.; Li, C.; Sun, Z. Crystallization regulation of Fe0@Fe3O4 using a g-C3N4/diatomite composite for enhancing photocatalytic peroxymonosulfate activation. Miner. Miner. Mater. 2022, 1, 8. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/mmm.2022.06

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.