High performance, low-cost rechargeable aluminum ion battery using Nb2CTx-MoS2 composite cathode

Abstract

Aluminum-ion batteries are among the promising low-cost researchable batteries with huge potential, due to their three-electron redox process, high theoretical capacity, and better safety compared to lithium-ion batteries. However, the reported capacity and cyclic stability still fall short of their theoretical values. This could be due to cathodic degradation, lattice distortion of working material, and anodic corrosion. To address these issues,

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The growing demand for safe and cost-effective energy storage devices is the driving force for efforts on different battery technologies. Conventional lithium-ion batteries have revolutionized energy storage technology and have been used as a major power source in portable electronics and even in electric vehicles. It has been proven to be a key energy storage device in the preceding decade with several shortcomings, such as safety, higher prices, and limited reserves[1,2]. In recent times, aluminum-ion batteries (AIBs) have been getting significant attention due to their lower cost (3rd most abundant element in the Earth’s crust)[3] and environmental safety. Additionally, AIBs have an extraordinary theoretical volumetric capacity of

A cathode with wide interlayer space to accommodate complex aluminum ions is required which would subsequently overcome the storage and lattice distortion challenges[17,18]. To address these challenges, multilayered structures such as iron chalcogenides hybrid cathodes (FeS2@C[19], NiCo2S4[20], and

In this work, the highly conductive, wide interlayer space characteristics of Nb2CTx and the pseudo-capacitive behavior of the MoS2 were exploited to improve electrochemical kinetics, enabling rapid charge-discharge rates and high stability. Nb2CTx enhances the overall conductivity of the cathode, facilitating faster ion movement within the electrode and improving the battery's rate capability[29]. Conversely, MoS2 can act as a buffer material, controlling large volume changes during ion intercalation and deintercalation within the cathode. This buffering effect can help improve the cycling stability of the AIB[30]. This unique combination of Nb2CTx and MoS2 supported by the green synthesis (HF-free etchant) of the Nb2CTx and AlCl3/[BMIM]Cl as an ionic liquid-based system has not been reported previously. Thus, Nb2CTx was prepared using FeCl3 as a green etchant in the presence of complexing agents. Meanwhile, triethylamine (TEA) was used for stabilizing its interlayer spacing and further modified with MoS2 to obtain a modified composite for the AIB cathode. For comparison, an AIB cell with pure Nb2CTx as a cathode was also prepared and tested. The pouch cell (2 × 2 inches) was fabricated using a cathode (Nb2CTx-MoS2 and

CHEMICALS AND MATERIALS

Nb2AlC MAX phase precursors, iron(III) chloride (FeCl3, 48%-54%), and TEA were purchased from Alfa Aesar. Anhydrous aluminum chloride (99.99%), 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride (98.0%), and aluminum foil of 0.01 mm thickness (99.99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The carbon paper, Celgard 2500 monolayer polypropylene (PP) membrane of 16 µm thickness, and aluminum laminated film were purchased from the local supplier. All the chemicals and reagents were consumed without additional purification.

Instrumentation

The synthesized Nb2CTx and its composite Nb2CTx-MoS2 were characterized by Field Emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM: Zeiss Merlin), high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD: Bruker D8 Advance), Raman spectroscopy, and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS: Amicus). Electrochemical studies such as cyclic voltammetry (CV), and impedance of the cell were recorded using a Gamry (Reference 3000) while the GCD was conducted using 8-channel battery analyzers BTS8-5V5A. XPS was used to analyze the interactions of cathode material with intercalated ions. After 500 consecutive cycles, the Nb2CTx-MoS2 cathode was removed from the cell, carefully cleaned with acetone, dried, and characterized by XRD, Raman spectroscopy, and XPS to study the structural changes that occurred during cycling.

Synthesis of MXenes and composite cathode

Nb2CTx MXenes were synthesized by following a HF-free green approach from Nb2AlC precursors by modifying a reported method[31]. In a typical wet etching process, a solution of FeCl3 0.1 M and tartaric acid as a complexing agent (1.2 M) was prepared in a closed Teflon bottle over an ice bath. Then, 2 g of

Likewise, the Nb2CTx-MoS2 composite was prepared by a hydrothermal method. In a modified approach, 4.8 g of Na2MoO4·2H2O and the required amount of thiourea were dissolved in 50 mL deionized water (DIW) with continuous stirring, followed by the addition of 76 mg of Nb2CTx dispersed in 3 mL of poly (dimethyldiallylammonium chloride) (PDDMAC) (20%). To maintain the pH of the solution at 6.5, the required amount of HCl was added. The mixture was then transferred into a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave and heated at 180 C for 24 h. The black-colored powder was washed several times to remove all impurities. Finally, the composite was dried in a vacuum oven and annealed at 400 C under constant Argon flow. Various concentrations and ratios of the respective salts were tested, and the above procedure yielded better results; hence, it was selected for further study. The overall synthesis process has been presented schematically in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of synthesis of Nb2CTx by green etchant (FeCl3 + TA). Synthesis of Nb2CTx-MoS2 composites by hydrothermal method. Additionally, the preparation of slurry with 80:10:10 ratio of active material, conducting carbon and PVDF binder respectively followed by pasting slurry on carbon paper is depicted.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To investigate the structure and morphology, Nb2CTx and composite Nb2CTx-MoS2 were studied through various instrumental techniques, including XRD, FE-SEM, HR-TEM, XPS, and Raman spectroscopy. XRD patterns of exfoliated few-layer Nb2CTx can be seen in Figure 2A. The figure shows the characteristic peak (002) of Nb2CTx has shifted to 2θ angle of 6.97°, compared to multilayered M-Nb2CTx at 9.46° and the precursor [Supplementary Figure 2] MAX phase (13.92°) after etching. This shift of basal plane (002) indicates an increase in the d-spacing to 4.27 nm (calculated by Braggs equation) after the etching of the aluminum layer and intercalation. These patterns are in line with the (PDF #30-0033) for the hexagonal phase Nb2C of space-group P63/mmc[29]. Figure 2B displays the hybrid diffraction patterns of the composite Nb2CTx-MoS2. Here, all characteristic peaks of Nb2CTx and MoS2 are visible, with slight shifts in peak position and changes in intensity; for instance, the Nb2CTx peak 6.97° has moved to a smaller angle of 6.44° compared to pure Nb2CTx[30]. Additionally, a new wide band emerges at 15.67° signifying the successful incorporation of MoS2. Likewise, the diffraction patterns observed at 19.12°, 22.74°, 32.19°, and 49.32° agree well with the literature[30]. Moreover, non-basal-plane peaks, such as (004), (103), and (106) at 13.92°, 36.12°, and 42.21°, respectively, have either eroded or experienced a decrease in intensity. These observations suggest structural modifications induced by the incorporation of MoS2 and intercalation processes.

Figure 2. Morphological and structural characterization of as-prepared Nb2CTx and its composite (A) XRD patterns of few layered

The layered morphology of the Nb2CTx is shown in the FE-SEM image [Figure 2C]. A few-layered accordion-like structure of Nb2CTx reflects the successful engraving of Al. Likewise, Figure 2D shows the FE-SEM images of the Nb2CTx-MoS2 composite; the substantial change in morphology with small flower-like crystallites of MoS2 covering the Nb2CTx flakes is observed, which confirms the formation of a well-defined composite and is assumed to enhance the conductivity and surface area of an electrode[32]. Figure 2E shows the HR-TEM images of the Nb2CTx transparent sheets and accordion-like shape due to the chemical etching of the Al atomic layers showing the few-layered arrangements of the as-prepared Nb2CTx. Similarly, Figure 2F shows the selected area diffraction (SAED) image; the diffraction rings demonstrate the (100), (102), (421) and (002) planes of the Nb2CTx crystals. Supplementary Figure 3A-C shows the Raman, TEM images for the prepared composite. Supplementary Figure 3B reveals clear lattice fringes associated with the Nb2CTx component. The measured interplanar d-spacing of the material was found to be approximately 4.27 nm. This value corresponds to a specific crystal plane within the Nb2CTx structure, providing information about its crystallinity. Besides, the TEM images offer direct visualization of the layered structure characteristic of both Nb2CTx and MoS2, as both materials consist of sheets or flakes stacked upon one another. In Supplementary Figure 3C, the individual layers of the Nb2CTx-MoS2 can be distinguished, appearing as relatively large, transparent regions. Their transparency in the TEM micrograph is due to the ultrathin nature of the Nb2CTx flakes. The presence of MoS2 in the composite is indicated by two features: Some of the observed transparent flakes may also be individual MoS2 sheets, depending on their orientation and thickness. Similarly, for Nb2CTx, the layered structure and very thin flakes can appear transparent under TEM. More prominently, the presence of MoS2 is evident as dark, irregularly shaped patches overlying the Nb2CTx flakes. These darker regions correspond to thick MoS2 sheets deposited on the surface of the Nb2CTx. The contrast difference between Nb2CTx and MoS2 allows for their visual distinction in the TEM image.

Figure 3A shows ex-situ XRD patterns for free and composite electrodes after successive ten and 500 charge/discharge cycles. A change in the XRD pattern is observed after the GCD process with the appearance of new peaks at 36.01°, 32.19°, and a rise in intensity for the pattern at 32.19° indicates the intercalation of ions during charge and discharge cycles in the cathode. These outcomes are in good agreement with the reported literature[33,34]. This was further confirmed by the Raman spectroscopy

Figure 3. The structural analysis and morphology of cathode after the charge-discharge process (A) Ex-situ XRD patterns for composite cathode after 10th and 500th charge/discharge cycles, (B) Raman spectra of the cathode at the 10th and after 500th cycle showing the changes in electrolyte chemistry, (C) FE-SEM images represent the cathode morphology after 500 cycles, (D) shows the high-resolution FE-SEM images after 500th cycle.

Supplementary Figure 5 presents the survey XPS analysis of Nb2CTx-MoS2, revealing the presence of Mo, S, Nb, C, and terminations resulting from the mild etching technique. To delve deeper into the anticipated operating mechanism, surface electronic states, and chemical composition, XPS tests were conducted on the electrode pre- and post-charging/discharge cycles. Figure 4A-C showcases the XPS spectra of the Nb 3d core levels of Nb2CTx-MoS2 before and after charging. Notably, during full charge, the binding energy of the Nb 3d core increased from 207.17 (Original) to 207.59 eV after fully charged, indicative of redox chemistry between the cathode surface and the intercalated ions[30]. Figure 4D and E elucidates changes in the XPS core levels of Al 2p and C 1s, respectively.

Figure 4. The XPS spectra depicting the change in position of binding energy of the major elements of the composite cathode before and after GCD process (A) XPS peaks for the Nb 3d core at fully charged state, (B) after discharging, (C) original composite cathode before GCD, (D) XPS peaks for the Al 2p at before charging, discharged, and fully charged stages, (E) XPS peaks for carbon in all three stages of original to charged.

Prior to GCD, minimal peaks are visible for Al 2p, suggesting a sparse presence of these elements. However, post-charging, a notable augmentation in Al 2p XPS peaks (at 75.56 and 199.56 eV, respectively) underscores the pronounced intercalation of [AlCl4]- ions within the cathode [Figure 4D]. This heightened intensity provides convincing evidence of successful ion intercalation. Similarly, upon full discharge, a noticeable reduction in both Al 2p signals signifies the substantial deintercalation of [AlCl4]- ions from the cathode. Additionally, a noticeable increase in binding energies (from 283.21 to 283.41 eV) in the C 1s spectra following charging/discharging sequences [Figure 4E] confirms the observed chemisorption phenomena between the cathode and embedded ions[30]. These observations collectively illustrate the interaction between electrode components and embedded ions during charge-discharge cycles, offering valuable insights into modifications in surface chemistry and the electrochemical behavior of the system[36].

Electrochemical study

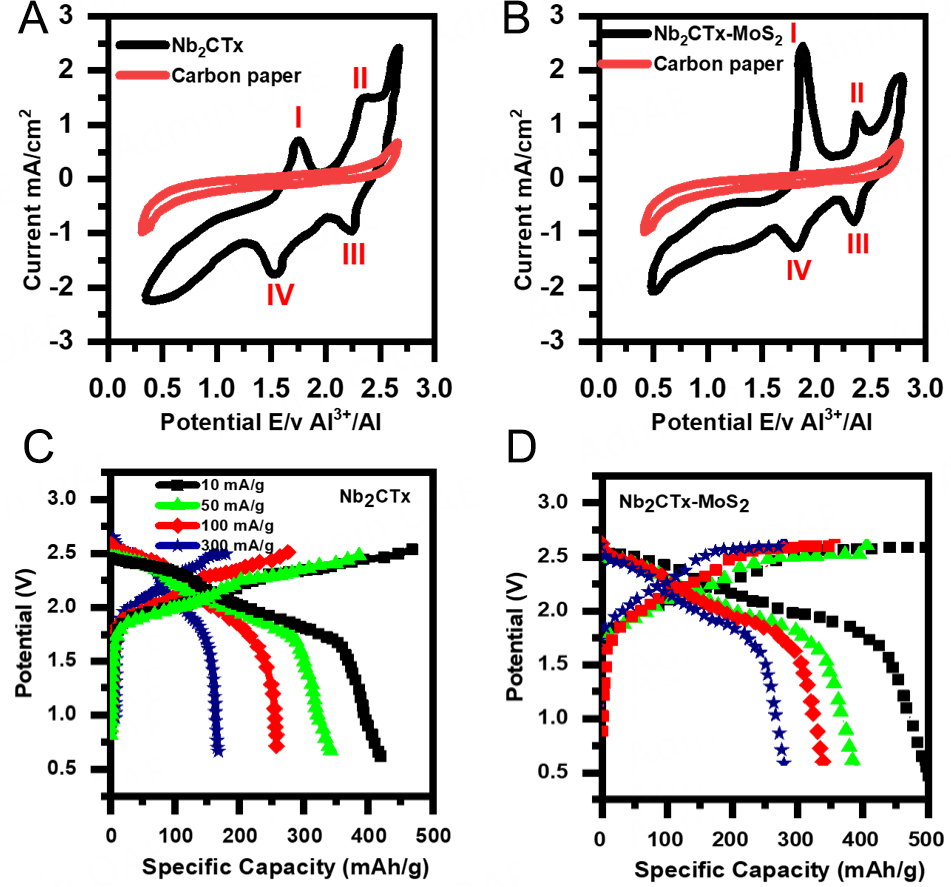

The performance of bare and composite cathodes was evaluated by performing CV and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) using Biologic VMP3 multichannel Potentiostat, while the GCD was conducted using 8-channel battery analyzers BTS8-5V5A; the cut-off voltage (upper/lower) was set as 2.8/0.5 V accordingly and all the electrochemical measurements were taken at room temperature. Figure 5 displays the CV and GCD curves of the bare Nb2CTx and Nb2CTx-MoS2 composite cathodes in an optimized 1.5 ratio of AlCl3/[BMIm]Cl electrolyte (details in Supplementary Material). Figure 5A depicts the CV responses of Nb2CTx cathodes recorded between the potential window of 0.5 to 2.7 V vs. Al3+/Al at a sweep rate of 0.1 mVs-1. It shows two anodic peaks of around 1.7-1.8 V (I) and 2.4-2.5 V (II), whereas the two cathodic peaks are at 2.2-2.1 V (III) and 1.6-1.5 V (IV), respectively. Likewise, Figure 5B displays CV curves for the composite cathode Nb2CTx-MoS2 and carbon paper at similar conditions. These complimentary anodic/cathodic peaks show the two-step electrochemical reaction between composite cathodes and Al which could be linked to aluminum ion intercalation and deintercalation at two different positions on the cathode; this behavior is well aligned with previous reports[37-39]. Significant changes have been observed at anodic peaks such as a shift in position and increase in current has been observed at

Figure 5. Cyclic voltammetry and GCD curves at different current densities for both electrodes (A) CV curve for the bare Nb2CTx at scan rate of 0.1 mV s-1 and carbon paper, (B) charge/discharge curves of Nb2CTx at current densities ranging from

The charge/discharge cycles of the bare Nb2CTx cathode [Figure 5C] were evaluated at various current densities extending from 10-300 mA/g. It has been observed that by varying the current densities as 10, 50, 100, and 300 mA/g, the charge/discharge capacity drops quickly with an increase in the current densities. In addition, it can be observed from Figure 5C that the charge/discharge plateaus split progressively and grow with the rise in the current density, which is due to the increased polarization, sluggish diffusion of complex ions through the Nb2CTx structure. It resulted in not only slow charge/discharge rates but also poor cycle stability. Likewise, Figure 5D depicts the charge/discharge curves of the cell with Nb2CTx-MoS2 cathodes at current densities of 10, 50, 100, and 300 mA/g. The specific capacities were observed to be 510, 400, 350, and 290 mAh/g, respectively, for the current densities of 10, 50, 100, and 300 mA/g. A comparatively slow decay and close specific capacities compared to bare Nb2CTx were observed. Similarly, in Figure 5D, the two charge plateaus are observed between 2.16-2.43 and 2.49-2.52 V, while the discharge plateaus are located around 2.5-2.43 and 2.10-1.89 V accordingly at a current density of 100 mA/g. It is evident that the composite cathode can maintain a capacity of 350 mAh/g after 50 to 500 cycles [Figure 6], which is much greater than the bare Nb2CTx cathode with better cycle stability. The slight variation in charge cut-offs is due to the effect of current densities on the electrochemical performance of the battery. At higher current densities, the battery experiences increased polarization and resistance, which can affect the charge-discharge voltage profile and lead to an earlier charge cut-off to avoid overcharging[40]. By contrast, at lower current densities, the system experiences less polarization, allowing for a more gradual and complete charging process, which can result in a slightly higher charge cut-off[41]. This approach ensures that the cell operates within safe limits across various current densities while optimizing performance.

Figure 6. Specific capacity of both electrodes for 500 cycles and corresponding coulombic efficiency of the cathodes for 500 GCD cycles (A) Long-term GCD curves and specific capacity of Nb2CTx at 100 mA/g current density, (B) long-term GCD curves and specific capacity of Nb2CTx-MoS2 at 100 mA/g current densities, (C) coulombic efficiency and cyclic performance of Nb2CTx at 100 mA/g, (D) Coulombic efficiency and cyclic performance for the Nb2CTx-MoS2 composite cathode at 100 mA/g.

The cycle stability and corresponding CE of AIBs were examined at a current density of 100 mA/g. Figure 6A portrays the cyclic stability and CE of the Nb2CTx cathode over 500 cycles. Initially, the Nb2CTx cathode boasted an impressive capacity of 400 mAh/g. However, after just 50 cycles, an abrupt decline resulted, with the capacity plateauing at 250 mAh/g over the subsequent 500 cycles at a steady current density of 100 mA/g. The accompanying CE, documented in Figure 6C, remained suboptimal at 83%. This trend may be attributed to coulombic interactions between the chloroaluminate ions and the strong electronegative terminals inherent in the Nb2CTx electrode materials[38]. Conversely, Figure 6B offers insight into the cycle stability of the modified Nb2CTx-MoS2 cathode over the same 500-cycle period at a

To further evaluate the electrochemical performance of the Nb2CTx-MoS2 cathode, EIS study was conducted on both bare and composite Nb2CTx-MoS2 cathodes across the frequency range of 105 to

Figure 7. (A) Nyquist plots of Nb2CTx at different cycles, (B) Nyquist plots of Nb2CTx-MoS2 composite at 10, 50, 100, and 200th cycles, (C) Open circuit potential and the equivalent circuit model of the pouch cell, (D) rate capability and coulombic efficiency of

Intercalation study

Figure 8 shows the schematic intercalating/de-intercalating process of AlCl4-, Cl- and Al3+ ions at the cathode during the charge/discharge process. The AlCl4- was observed to be the key ion for the electrochemistry of batteries. The AlCl3/[BMIm]Cl ILE comprises two key anionic species at room temperature (AlCl4- and

Figure 8. Optimized structure of the respective ions, overall chemistry of electrolyte and complex ion formation, the model battery operation where the ions flow to respective electrodes during the charge and discharge process is observed and the ion intercalation/deintercalation during the charge-discharge process at the cathode and anode.

CONCLUSION

For the first time, the Nb2CTx was synthesized by HF-free green etchants and transformed into a Nb2CTx-MoS2 composite cathode to obtain a unique syngeneic combination to improve the performance of the AIB. The developed composite (Nb2CTx-MoS2) cathode showed a high capacity of 350 mAh/g, and good cycle life, which is significantly higher than previously reported AIBs. The XRD, XPS, and FE-SEM images confirmed the successful fabrication of the Nb2CTx-MoS2 composite with enhanced electrochemical characteristics. The AIB was subjected to 500 charge/discharge cycles at the current density of

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Methodology, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, writing - original draft: Mahar, N.

Methodology, supervision, writing - review & editing: Abdo Saleh, T.

Concept, visualization, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing: Al-Ahmed, A.

Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing - review & editing, project administration, funding acquisition: Al-Saadi, A. A.

Availability of data and materials

Data and materials are available and can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Financial support and sponsorship

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding from the King Fahd University of Petroleum & Minerals (KFUPM), Saudi Arabia, through grant (PAES-2400).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Chayambuka, K.; Mulder, G.; Danilov, D. L.; Notten, P. H. L. From Li-ion batteries toward Na-ion chemistries: challenges and opportunities. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2020, 10, 2001310.

2. Fan, E.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.; et al. Sustainable recycling technology for Li-ion batteries and beyond: challenges and future prospects. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 7020-63.

3. Zhou, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, D.; et al. Cathode materials in non-aqueous aluminum-ion batteries: progress and challenges. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 26454-65.

4. Ponnada, S.; Kiai, M. S.; Krishnapriya, R.; Singhal, R.; Sharma, R. K. Lithium-free batteries: needs and challenges. Energy. Fuels. 2022, 36, 6013-26.

5. Nayem SM, Ahmad A, Shaheen Shah S, Saeed Alzahrani A, Saleh Ahammad AJ, Aziz MA. High performance and long-cycle life rechargeable aluminum ion battery: recent progress, perspectives and challenges. Chem. Record. 2022, 22, e202200181.

6. Ma, D.; Li, J.; Li, H.; et al. Progress of advanced cathode materials of rechargeable aluminum-ion batteries. Energy. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 0088.

7. Raić, M.; Lužanin, O.; Jerman, I.; Dominko, R.; Bitenc, J. Amide-based Al electrolytes and their application in Al metal anode-organic batteries. J. Power. Sources. 2024, 624, 235575.

8. Wu, Y.; Lin, W.; Tsai, T.; Lin, M. Unveiling the reaction mechanism of aluminum and its alloy anode in aqueous aluminum cells. ACS. Appl. Energy. Mater. 2024, 7, 3957-67.

9. Wang, H.; Gu, S.; Bai, Y.; et al. Anion-effects on electrochemical properties of ionic liquid electrolytes for rechargeable aluminum batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2015, 3, 22677-86.

10. Macfarlane, D. R.; Forsyth, M.; Howlett, P. C.; et al. Ionic liquids and their solid-state analogues as materials for energy generation and storage. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 15005.

11. Liu, T.; Vivek, J. P.; Zhao, E. W.; Lei, J.; Garcia-Araez, N.; Grey, C. P. Current challenges and routes forward for nonaqueous lithium-air batteries. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 6558-625.

12. Hu, Y.; Fan, L.; Rao, A. M.; et al. Cyclic-anion salt for high-voltage stable potassium-metal batteries. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2022, 9, nwac134.

13. Ng, K. L.; Lu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Singh, C. V.; Azimi, G. Fundamental insights into electrical and transport properties of chloroaluminate ionic liquids for aluminum-ion batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2021, 125, 15145-54.

14. Pastel, G. R.; Chen, Y.; Pollard, T. P.; et al. A sobering examination of the feasibility of aqueous aluminum batteries. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 2460-9.

15. Jayaprakash, N.; Das, S. K.; Archer, L. A. The rechargeable aluminum-ion battery. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 12610.

16. Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Ji, Y.; Ma, J.; Yu, H. Emerging nonaqueous aluminum-ion batteries: challenges, status, and perspectives. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1706310.

17. Ates, M.; Chebil, A.; Yoruk, O.; Dridi, C.; Turkyilmaz, M. Reliability of electrode materials for supercapacitors and batteries in energy storage applications: a review. Ionics 2022, 28, 27-52.

18. Wang, S.; Kravchyk, K. V.; Pigeot-rémy, S.; et al. Anatase TiO2 nanorods as cathode materials for aluminum-ion batteries. ACS. Appl. Nano. Mater. 2019, 2, 6428-35.

19. Zhao, Z.; Hu, Z.; Jiao, R.; et al. Tailoring multi-layer architectured FeS2@C hybrids for superior sodium-, potassium- and aluminum-ion storage. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2019, 22, 228-34.

20. Li, S.; Tu, J.; Zhang, G. H.; Wang, M.; Jiao, S. NiCo2S4 nanosheet with hexagonal architectures as an advanced cathode for Al-ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018, 165, A3504.

21. Yang, W.; Lu, H.; Cao, Y.; Xu, B.; Deng, Y.; Cai, W. Flexible free-standing MoS2/carbon nanofibers composite cathode for rechargeable aluminum-ion batteries. ACS. Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 4861-7.

22. Geng, L.; Scheifers, J. P.; Fu, C.; Zhang, J.; Fokwa, B. P. T.; Guo, J. Titanium sulfides as intercalation-type cathode materials for rechargeable aluminum batteries. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017, 9, 21251-7.

23. Xing, W.; Li, X.; Cai, T.; et al. Layered double hydroxides derived NiCo-sulfide as a cathode material for aluminum ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta. 2020, 344, 136174.

24. Wang, S.; Jiao, S.; Wang, J.; et al. High-performance aluminum-ion battery with CuS@C microsphere composite cathode. ACS. Nano. 2017, 11, 469-77.

25. Pan, W. D.; Liu, C.; Wang, M. Y.; et al. Non-aqueous Al-ion batteries: cathode materials and corresponding underlying ion storage mechanisms. Rare. Metals. 2022, 41, 762-74.

26. Yuan, D.; Dou, Y.; Wu, Z.; et al. Atomically thin materials for next-generation rechargeable batteries. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 957-99.

27. VahidMohammadi, A.; Hadjikhani, A.; Shahbazmohamadi, S.; Beidaghi, M. Two-dimensional vanadium carbide (MXene) as a high-capacity cathode material for rechargeable aluminum batteries. ACS. Nano. 2017, 11, 11135-44.

28. Zhao, J.; Wen, J.; Bai, L.; et al. One-step synthesis of few-layer niobium carbide MXene as a promising anode material for high-rate lithium ion batteries. Dalton. Trans. 2019, 48, 14433-9.

29. Li, J.; Zeng, F.; El-Demellawi, J. K.; et al. Nb2CTx MXene cathode for high-capacity rechargeable aluminum batteries with prolonged cycle lifetime. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2022, 14, 45254-62.

30. Tan, B.; Lu, T.; Luo, W.; Chao, Z.; Dong, R.; Fan, J. A novel MoS2-MXene composite cathode for aluminum-ion batteries. Energy. Fuels. 2021, 35, 12666-70.

31. Mahar, N.; Al-ahmed, A.; Al-saadi, A. A. Synthesis of vanadium carbide MXene with improved inter-layer spacing for SERS-based quantification of anti-cancer drugs. Appl. Surface. Sci. 2023, 607, 155034.

33. Yu, Z.; Tu, J.; Wang, C.; Jiao, S. A rechargeable Al/graphite battery based on AlCl3/1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride ionic liquid electrolyte. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 3018-24.

34. Nahian, M. K.; Reddy, R. G. Electrical conductivity and species distribution of aluminum chloride and 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride ionic liquid electrolytes. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2023, 36, e4549.

35. Zheng, Y.; Dong, K.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Lu, X. Density, viscosity, and conductivity of lewis acidic 1-butyl- and 1-hydrogen-3-methylimidazolium chloroaluminate ionic liquids. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 2013, 58, 32-42.

36. Chen, C.; Shi, M.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhao, L.; Yan, C. Al-Intercalated MnO2 cathode with reversible phase transition for aqueous Zn-Ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 422, 130375.

37. Yuan, Z.; Lin, Q.; Li, Y.; Han, W.; Wang, L. Effects of multiple ion reactions based on a CoSe2/MXene cathode in aluminum-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2211527.

38. Angell, M.; Pan, C. J.; Rong, Y.; et al. High coulombic efficiency aluminum-ion battery using an AlCl3-urea ionic liquid analog electrolyte. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017, 114, 834-9.

39. Xu, H.; Bai, T.; Chen, H.; et al. Low-cost AlCl3/Et3NHCl electrolyte for high-performance aluminum-ion battery. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2019, 17, 38-45.

40. Seong, W. M.; Yoon, K.; Lee, M. H.; Jung, S.; Kang, K. Unveiling the intrinsic cycle reversibility of a LiCoO2 electrode at 4.8-V cutoff voltage through subtractive surface modification for lithium-ion batteries. Nano. Lett. 2019, 19, 29-37.

41. Nölle, R.; Beltrop, K.; Holtstiege, F.; Kasnatscheew, J.; Placke, T.; Winter, M. A reality check and tutorial on electrochemical characterization of battery cell materials: how to choose the appropriate cell setup. Mater. Today. 2020, 32, 131-46.

42. Chen, C.; Xie, X.; Anasori, B.; et al. MoS2-on-MXene heterostructures as highly reversible anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 1846-50.

43. Zhu, N.; Zhang, K.; Wu, F.; Bai, Y.; Wu, C. Ionic liquid-based electrolytes for aluminum/magnesium/sodium-ion batteries. Energy. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2021, 9204217.

44. Li, Z.; Niu, B.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Kang, F. Rechargeable aluminum-ion battery based on MoS2 microsphere cathode. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2018, 10, 9451-9.

45. Shen, X.; Sun, T.; Yang, L.; et al. Ultra-fast charging in aluminum-ion batteries: electric double layers on active anode. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 820.

46. Zheng, L.; Yang, H.; Bai, Y.; Wu, C. Multielectron reaction of AlCln in borophene for rechargeable aluminum batteries. Energy. Mater. Adv. 2022, 2022, 0005.

47. Pradhan, D.; Reddy, R. G. Mechanistic study of Al electrodeposition from EMIC-AlCl3 and BMIC-AlCl3 electrolytes at low temperature. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2014, 143, 564-9.

48. Elterman, V.; Shevelin, P. Y.; Yolshina, L.; Borozdin, A. Features of aluminum electrodeposition from 1,3-dialkylimidazolium chloride chloroaluminate ionic liquids. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 351, 118693.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].