Meningeal inflammation and multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS). Inflammation in MS is characterized by infiltration of peripheral immune cells into the CNS, especially in the meninges.[1-4] The infiltration into meninges, which has been referred to as tertiary lymphoid tissues (TLTs), is a likely first step preceding infiltration into the CNS parenchyma. These invading autoreactive immune cells destroy myelin, the insulation surrounding neuronal axons, and cause demyelination in subpial and cortical areas, promoting disease pathogenesis. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a widely used murine model of MS, also shares this characteristic.[5,6] However, what cellular components and molecular pathways support infiltrating lymphocyte retention and production within the meninges as well as further invading into the CNS parenchyma are still not clear. Pikor et al.[7] first reported that stromal cells in the inflamed CNS meninges (TLTs) play an important role in the neuroinflammatory process of MS. They also demonstrated that collaboration between the encephalitogenic T helper 17 (Th17) cell and lymphotoxin pathways contributes to the formation of TLTs.

First, they made use of the SJL/J EAE model, which mimics progressive MS, to investigate the location and cellular composition of TLTs.[7] They found that T cells were the initial population in meningeal TLTs, while B cells invaded the meninges later. Based on a previous report showing the importance of Th17 cells in promoting TLTs,[6,7] they established an adoptively transferred encephalitogenic Th17 in the SJL/J EAE model. They found that Th17 cells could rapidly populate, proliferate, and secrete cytokines in the meninges. The TLTs formed by Th17 cells and B cells were also associated with subpial and parenchyma demyelination, as shown by histological staining.[7] Thus the authors have established a good model (Th17 cells A/T model) for further investigation of the cellular and molecular mechanisms of TLTs.

What are the roles of infiltrating Th17 cells in the remodeling of stromal cells in the meninges? They found that 1 out of the 4 populations of stromal cells in meninges, meningeal FRC-like cells [a subpopulation of gp38(+)CD31(-) which are PDGFα-PDGFβ+ and PDGFα+PDGFβ+], which closely resembled lymph node fibroblastic reticular cells, were dramatically increased in EAE meninges regardless of the genetic background of mice.[7] From in vivo and in vitro studies, they found that Th17 cells and their soluble mediators IL-17 and IL-22 could remodel fibroblasts and up-regulate extracellular matix proteins and metal matrix proteinase 9, chemokines (murine macrophage inflammatory protein-3α, murine exodus-2, human GRO/melanoma growth stimulatory activity), and cytokines in the meninges. Inhibition of both IL-17 and IL-22 resulted in reductions in the fibronectin network and clinical severity of disease.[7] These results indicate that infiltrating Th17 cells contribute to building a suitable environment in the meninges to support their survival.

How do stromal cells in TLTs support infiltrating Th17 cell retention and proliferation in the meninges? Lymphotoxin beta receptor (LTBR) is a member of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily[8] and is expressed on stromal cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages, whereas its ligand LTab is expressed on embryonic Lymphoid tissue inducer cells, as well as innate lymphoid cells, B cells, natural killer cells, and activated T cells. Stromal cell chemokine secretion and stromal cell maturation are depended on the lymphotoxin pathway. The author applied LTBR-Ig treatment or used LTBR-deficient mice in a Th17 cells A/T model and found that stromal cell remodeling was comparable between wild-type mice and LTBR-deficient mice. TLT formation was also undisturbed in LTBR-Ig-treated mice.[7] All of this evidence suggests that the early steps of TLT formation are not dependenton the leukotriene pathway. Interestingly, they also found that LTBR signaling in radio-resistant stromal cells was required for the maturation of stromal cells and accumulation of B cells in TLTs as well as for T cell cytokine (IL-17 and interferon-γ) production in the CNS by using bone marrow chimeric mice which had LTBR deficient in radial-sensitive cells in Th17 cell A/T EAE model.[7] Meninges stromal cells activated by Th17 cells and their cytokines IL-22 and IL-17 also secreted IL-6 and IL-23, which were involved in Th17 cell polarization and maintenance.[7] So the specific stromal cells in TLTs, which share similarities with lymphoid tissue stroma, interact with Th17 cells and support Th17 cell retention and proliferation in meninges.

Furthermore, expression of lymphotoxin αβ (Ltαβ) on Th17 cells was also found to be required to propagate inflammation and disease progress in Th17 cell A/T EAE model.[7] Moreover, increased levels of Ltαβ (LTBR ligand) on activated CD4+ T cells were found in MS patients, but not in healthy controls.[7]

Collectively, these results suggest that infiltrating Th17 cells remodel the meningeal stromal cells and initiate the formation of TLTs during EAE. The remodeled stromal cells retain and promote the production of Th17 and the accumulation of B cells. The collaboration between LTB on Th17 cells and LTBR on meningeal radio-resistant cells is very crucial for the induction and progression of MS. This highlights the importance of the interaction between immune cells and non-immune cells (stromal cells) in the pathogenesis of MS.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Aloisi F, Pujol-Borrell R. Lymphoid neogenesis in chronic inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 2006;6:205-17.

2. Magliozzi R, Howell O, Vora A, Serafini B, Nicholas R, Puopolo M, Reynolds R, Aloisi F. Meningeal B-cell follicles in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis associate with early onset of disease and severe cortical pathology. Brain 2007;130:1089-104.

3. Howell OW, Reeves CA, Nicholas R, Carassiti D, Radotra B, Gentleman SM, Serafini B, Aloisi F, Roncaroli F, Magliozzi R, Reynolds R. Meningeal inflammation is widespread and linked to cortical pathology in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2011;134:2755-71.

4. Choi SR, Howell OW, Carassiti D, Magliozzi R, Gveric D, Muraro PA, Nicholas R, Roncaroli F, Reynolds R. Meningeal inflammation plays a role in the pathology of primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Brain 2012;135:2925-37.

5. deLuca LE, Pikor NB, O'Leary J, Galicia-Rosas G, Ward LA, Defreitas D, Finlay TM, Ousman SS, Osborne LR, Gommerman JL. Gommerman, Substrain differences reveal novel disease-modifying gene candidates that alter the clinical course of a rodent model of multiple sclerosis. J Immunol 2010;184:3174-85.

6. Peters A, Pitcher LA, Sullivan JM, Mitsdoerffer M, Acton SE, Franz B, Wucherpfennig K, Turley S, Carroll MC, Sobel RA, Bettelli E, Kuchroo VK. Th17 cells induce ectopic lymphoid follicles in central nervous system tissue inflammation. Immunity 2011;35:986-96.

7. Pikor NB, Astarita JL, Summers-Deluca L, Galicia G, Qu J, Ward LA, Armstrong S, Dominguez CX, Malhotra D, Heiden B, Kay R, Castanov V, Touil H, Boon L, O'Connor P, Bar-Or A, Prat A, Ramaglia V, Ludwin S, Turley SJ, Gommerman JL. Integration of Th17- and Lymphotoxin-Derived Signals Initiates Meningeal-Resident Stromal Cell Remodeling to Propagate Neuroinflammation. Immunity 2015;43:1160-73.

8. Lu TT, Browning JL. Role of the Lymphotoxin/LIGHT System in the Development and Maintenance of Reticular Networks and Vasculature in Lymphoid Tissues. Front Immunol 2014;5:47.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Liu, L. P. Meningeal inflammation and multiple sclerosis. Neurosciences. 2016, 3, 145-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/2347-8659.2016.22

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

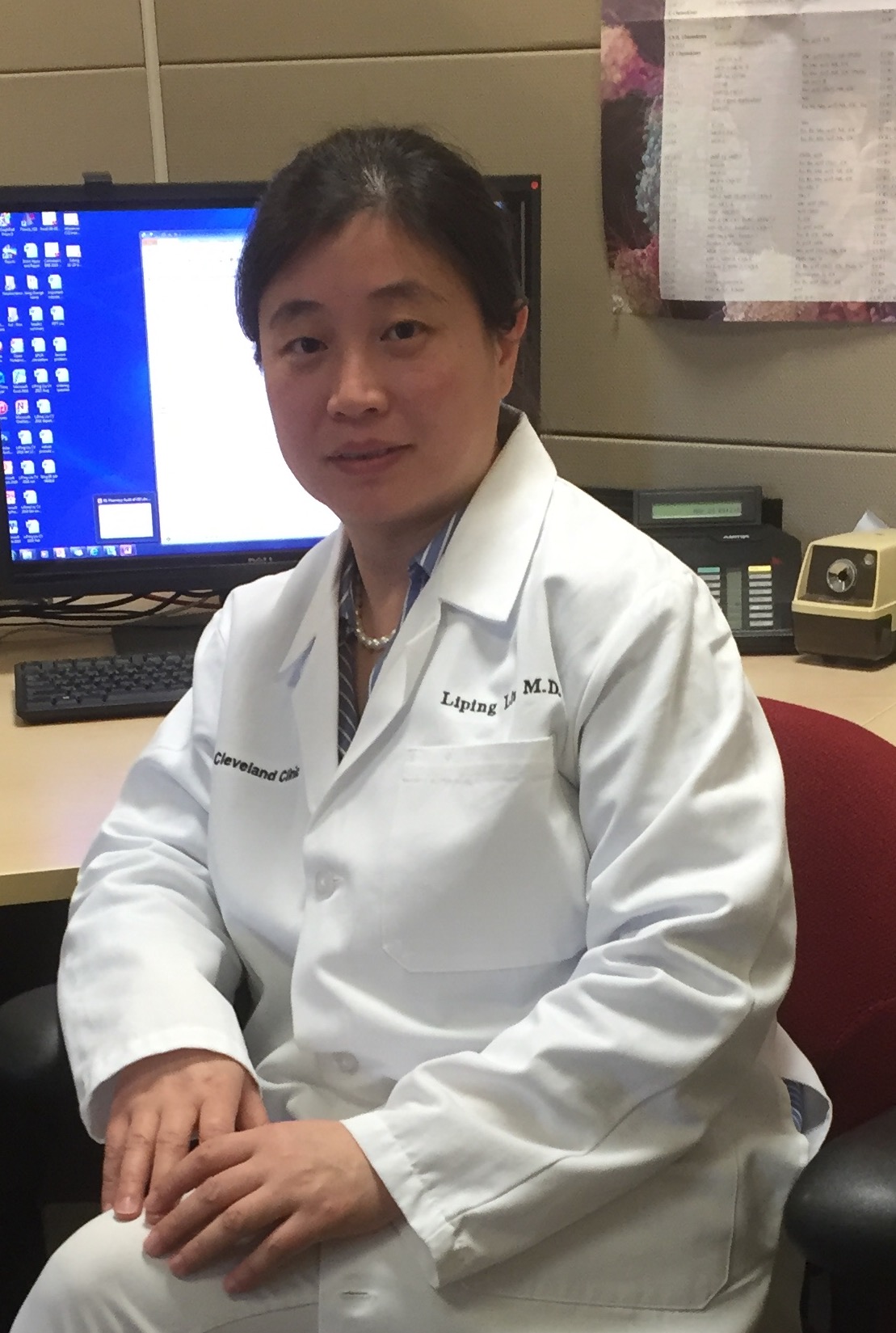

Author Biographies

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.